Structured almost like a classical, Greek tragedy, H. explores mass hysteria. Co-directors Daniel Garcia and Rania Attieh discuss their filmmaking process at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival.

The new film from co-directors Daniel Garcia and Rania Attieh, H., which premiered in the NEXT section at Sundance is an unconventional science fiction thriller. Structured almost like a classical, Greek tragedy, it explores mass hysteria with remarkable calm.

This is the third film from partners Garcia and Attieh who also write and edit their films together. In fact, their creative collaboration, and the way they talk over each other, often resembles the young couple in their film, H. who are also artistic collaborators. I sat down with Garcia and Attieh after the World Premiere of their film at Sundance to discuss the surprisingly true stories that so many of the film’s bizarre events are based on, how they created ordered chaos, and their exploration of glitch art.

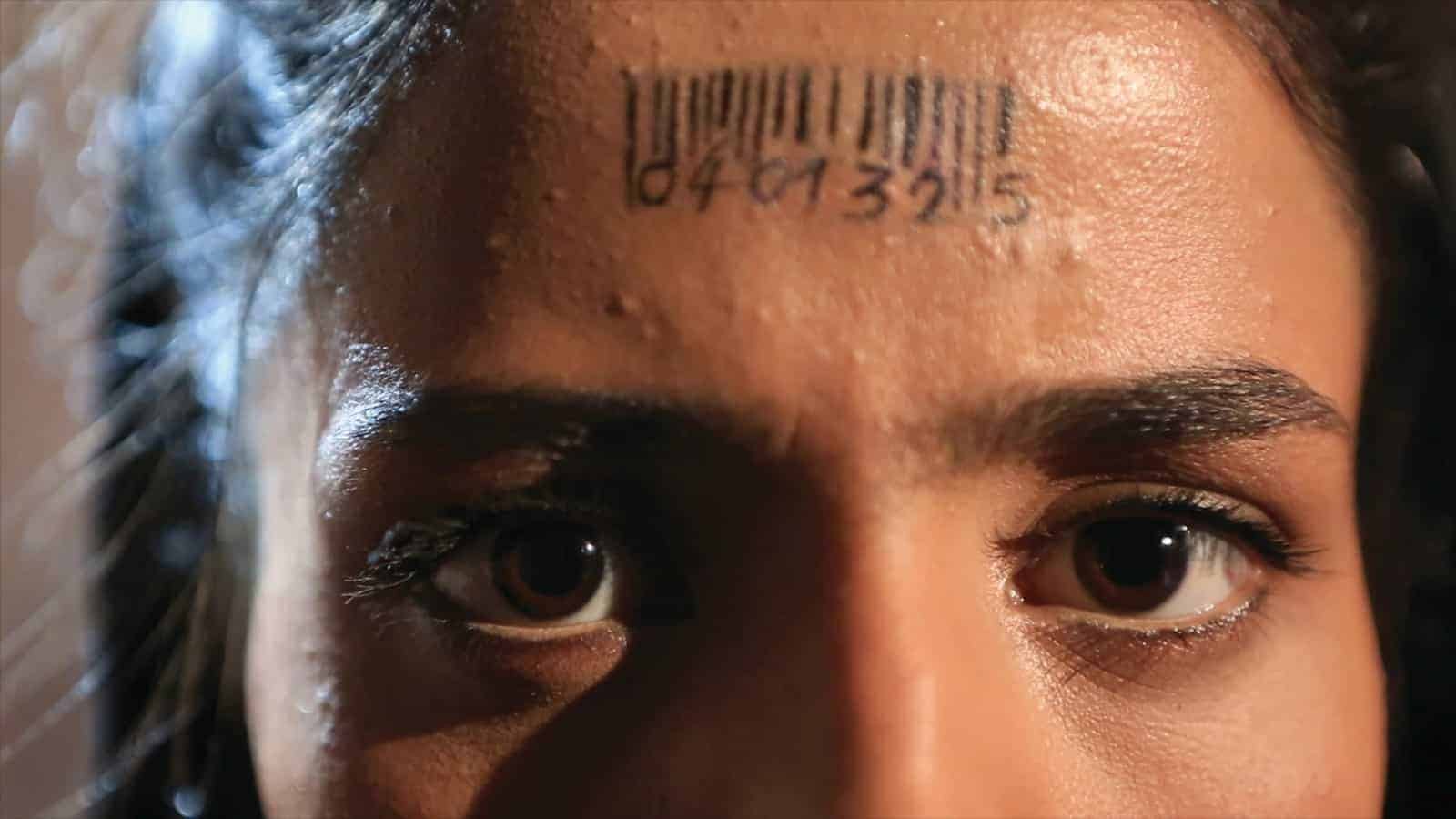

H. follows two couples, each involving a woman named Helen in Troy, New York, where eerie things start happening. The elder, middle-aged Helen (Robin Barrett, whom you may remember from Inside Llewyn Davis for her great line reading of “Where’s its scrotum, Llewyn?!”) is ensconced in reborn culture: she has a very life-like newborn doll that she cares for as if it’s a real baby. The younger Helen (Rebecca Dayan) appears to be pregnant given her large bump, lactating breasts, and positive pregnancy test results — but she isn’t. Both of these women find themselves in a strange world where a meteor crash can send a town into panic.

Attieh explained, “We didn’t want to make a regular sci-fi movie. We wanted to make a specific twist on the genre, something more in your imagination, more unresting than ‘here’s all the houses. They’re burned, and the people are dead.’ We wanted this distance to the genre. We wanted to create a new experience of a genre. You’re not sitting going, ‘now they’re going to show us how the houses were burned and the cars were burned and there’s a crater in the ground. We wanted you to take a ride and be surprised at every turn.’ ”

Perhaps the most surprising thing about the film is that all of the elements that seem most strange and most unrealistic are all actually based on actual fact. There is a rich reborn community, which Attieh discovered on a trip to South America. Attieh and Garcia spent countless hours researching it for the film. Garcia recalled, “We came across certain things like YouTube videos of how [women with newborn dolls] feed [them], or what they say when they feed, or how they talk to their husband when their husband passes by when they’re making the video.”

Garcia explained that research is key to their writing process, “You get all these insights into that quote-un-quote character that we’re trying to build. We can feed those instances up into the writing. Similarly, with the scene where she [Robin Bartlett] comes out, and her window’s broken, because she left the baby in the car.” In the film, a cop had thought there was a real, live baby, abandoned and suffocating in the car in the dead of winter so he had broken into Helen’s car. Attieh added, “That happened in Australia with a woman that collects reborn dolls. And we thought, this is an amazing scene, because if these dolls exist, then that scene makes perfect sense. So we wanted to write it in the movie.”

The film’s four chapters, which alternate between the two Helens, are punctuated by the image of a giant head from a statue of Helen of Troy, floating mysteriously down the Hudson river. This, too, was based on a true story that Garcia and Attieh had read about in a news article. Attieh recalled, “It actually had a different-looking head — a head of a man floated, a greek statue. It was made of styrofoam.” Attieh elaborated, “While we were writing, that news article came up. We needed a chapter breaker. We had a very specific design for the film. We wanted a very formal, literary, old school way of chaptering the film, versus the modern elements in it. We needed the bridge, and that came out, and we thought, ‘this is awesome, a head floating down a river.’ There’s something that, I guess, we both are super-interested in, is like all the absurd unbelievable elements in life that are actually completely real.”

Strange things start happening in the town. Many people go missing, including the older Helen’s husband. The magnetic poles get reversed, and a screw starts falling upwards. High-pitched noises become ubiquitous, giving men migraines and leading them to stand still against and facing the walls outdoors. Meanwhile, our protagonists calmly watch this madness on the television news from the comfort of their own homes.

The news broadcasts started as a device for exposition, but soon became much more central to the story. Garcia commented that “at one of the earlier stages, someone that read the script mentioned that the news stations kind of resembled a Greek chorus.” Attieh added, “If you are in a panic, you sit at home. You watch TV. I grew up in a country [Lebanon] that had a civil war for 15 years. You have bombs outside. You don’t go outside. You sit at home [and] listen to the radio. You know from the radio what is happening. You feel safer wherever you stay. And [in the film,] we knew that we wanted to spend two days with the couple inside the house. And it is impossible that they would not want to know what was happening.”

There’s also an order to the chaos that happens in the film. Cloud formations start to appear in perfect grids; it’s not quite right because it’s so organized. Yet their research revealed that this could happen. Garcia elaborated, “if something was happening in your city, and you saw these [things happening], and it was a little ominous, and these clouds appeared, you’d be like ‘Holy shit, this is getting really crazy.’ So that was something we were feeding off, too.” But, Attieh is careful to note, “It’s not enough crazy that you would pack up and leave, but it’s crazy enough that people will talk about it and feel like something strange is happening.”

Striking that balance of creating something eerie and off-putting that wasn’t catastrophic was a major challenge in the writing process. Attieh explained how they achieved this: “We wrote all the scenes on cards, and put them on the ground. And we tagged when weird things are happening in different colours. Like, how many times [do] the clouds [appear in grids]? Where do they come [in the film]? Because we have two different stories — two women — so we had to organize it, visually. And if it felt balanced and orderly, visually, for us, where the things are tagged — if it looked beautiful like this, then we thought it would make sense if we cut it that way.”

At one point in the film, the younger Helen finds herself drawn deeper and deeper into the forest in town where a group of people are lying in a grid in the fetal position; she joins them. Creating the order in that grid of people was a very precise, meticulous process. Attieh recalled, “We had the [whole] team on the ground, [and we were] organising them into grids. We had a crane, and we would look at the monitor, and be like “OK, guy with the hat should move a little. This woman should slide a little.” We wanted it to feel very organised.”

As the young Helen makes her way into the forest, en route to finding this grid of people in the snow, the film itself actually starts to glitch and become pixilated. This was part of the directors’ attempt to create a sci-fi film for the digital, super-modern age. Garcia noted, “The film starts with a little bit of interference. We wanted to build interference into it. The first television starts glitching.”

Attieh continued, “Daniel wanted to play with sound and image glitch because the digital image gets interference. And if something like this [the strange things happening in town], that is creating a change in the magnetic power — if a screw can fall upward — then definitely the image would glitch. So because we had the idea of the glitches in image and the breaks in sound. Her [young Helen’s] nightmare is based on her experience, her fears and anxieties — the actual images in real life. No one created it. It’s a combo that feels surreal, but the elements are all real. [Daniel] wanted to have her feel trapped in an interference, because that’s what she remembers. The last couple of days, we assume, she’s [been] watching TV, and there’s always a digital interference. So she gets caught in the interference.”

Picking up on that thought, Garcia added, “We thought about the fact that, for the majority of the film, the interference was coming from the TVs that she’s watching, or the radios she’s listening to — you know, when she hears that weird sound. And it slowly, over the film, this interference, whatever it is, has not only seeped into her internal psyche, but in the force, when it does start to glitch on the screen in the film. That glitch has now crossed over into the fourth wall. It’s now interfering [with] the film. It’s not just interfering [with] them.”

When asked to elaborate on the technical elements of how he actually created this glitch, Garcia explained, ”The general idea for that, and the technique, is based on something called datamoshing — an internet age and digital kind of pixilation and interference. It’s basically just glitch art. It’s stuff that happens with digital media that people have found a way to manipulate and create. It’s strictly an internet, digital code glitch. It happens with i-frames, p-frames. It’s very technical, but it just happens to be the way digital and internet media is created, and these kinds of things happen sometimes. If you’re watching just regular digital TV, and like, a car passes, something happens, it’ll do it. It’ll get a little pixilated, and it’ll freeze.”

The way they achieved these glitches was by taking the clip they wanted to glitch, and Garcia explained, “running it through this software program, and it will randomly glitch it up. So, if you do it enough you’ll have enough glitched material by which you can then say ‘let’s try this.’ Then you can try the other one, and ‘oh, that looks a little better.’ It’s just a process of trial and error, over and over. Let’s take this glitch feed it in, feed it in.” There is a way to glitch the film manually, but the film was made so quickly, in just four months, that they didn’t have that luxury.

The film is a slow burn, as all of the eerie things piece together, and we start to see parallels between the two Helens and their issues surrounding motherhood. I’m not sure it always makes sense or works, but it’s certainly thought-provoking and engaging. It’s a gorgeous film to behold with its icy aesthetic that’s drained of colour. One thing is for sure though: this is a film that will get you talking and arguing, and Garcia and Attieh are a pair to watch. They’re pushing the boundaries of the medium, and I expect they’ll only continue to do innovative work. This film, whatever its flaws, demands to be seen.

This is an edited version of the article originally published on February 9, 2015 as part of our Sundance 2015 coverage.