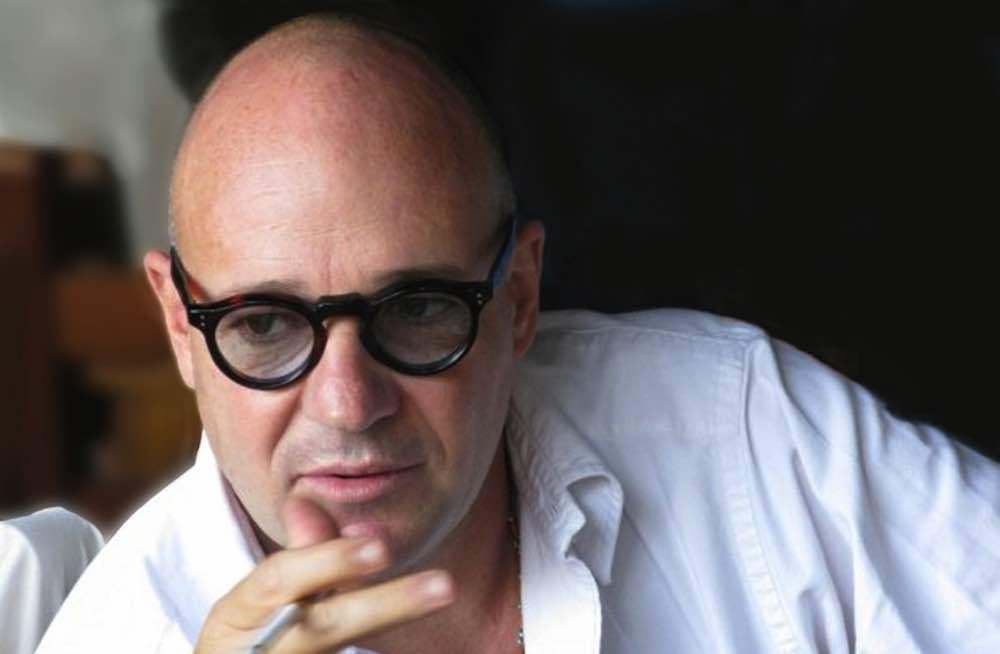

In our second behind-the-scenes look at the film, Gianfranco Rosi talks editing Fire at Sea: how he narrows down his documentary footage and shapes it into a narrative in the editing room. This is an excerpt from the ebook In Their Own Words: Documentary Masters Vol. 1 which is available for purchase here.

Italian director Gianfranco Rosi spent a year and half living in Lampedusa to film Fire at Sea, his new film about the small Italian island that became an immigration hub for refugees from Africa and Libya. He was fascinated by the separation between the Lampedusa locals and the migrants: they share such a small space but never interact. Because Rosi says, “Most of the time is, for me, about losing moments,” he only shot 80 or 90 hours of footage — less than half of what Frederick Wiseman shot for National Gallery, which was shot over a few weeks. But shaping that footage into an emotional, coherent narrative was s complex process. I sat down with Rosi to discuss how he chooses footage, how he shapes the narrative, and how he knows when a movie is done.

[clickToTweet tweet=”I never watch my footage while I’m filming. But I film everything myself so my memory is very strong.” quote=”I never watch my footage while I’m filming. But I film everything myself so my memory is very strong, what works or what doesn’t work. “]

Seventh Row (7R): What was the process of narrowing down all that footage and figuring out what kinds of sounds you wanted to accompany everything?

Gianfranco Rosi (GR): The most important thing in the film was the 30 second scene of death. This was the most difficult part. From the beginning, I knew that I wanted to put that image there. But I didn’t know where. The whole film somehow was built to arrive at this moment, to create this structure. And then not only arriving there, which is a 30 second scene, but also to be able to leave there and creating this mourning, to give respect to this moment here through silence. The last part of the film is 25, 28 minutes of complete silence.

It was very important that with all the people that accompany me in this film, the kids, the doctor, the migrants, every scene was a trajectory, a journey, in order to arrive at this scene. Also, the silence was very important, the space between notes. I wanted to use all the language of the narrative of fiction in the film, although everything is real that happened.

7R: How did you figure out where you wanted to begin the film?

Gianfranco Rosi: It was somehow very chronological, the film. I knew that I wanted to begin with the kid. I couldn’t begin with him with the lazy eye, when he puts the glasses on, because that was something that was later. I could not use the footage I’d shot before anymore because his life changes, so somehow that was logical. So there were things that were very obvious that had to go later in the film. The opening was my first day of shooting with him, looking for this branch to build the slingshot.

[clickToTweet tweet=”If I give the same footage to a hundred editors, I would have a hundred different films.” quote=”If I give the same footage to a hundred editors, I would have a hundred different films.”]

7R: So the challenge was more figuring out what order to put the characters in?

Gianfranco Rosi: How to interact between the migrants and the characters because you have to create this mood. It can’t just be arbitrary from scene to scene. There has to be a link, which is an emotional link for me, an association of elements. If I give the same footage to a hundred editors, I would have a hundred different films.

To read the rest of the interview with Gianfranco Rosi, purchase a copy of the ebook In Their Own Words: Documentary Masters, which is available here.

[wcm_restrict]

7R: What is your process for when you’re shaping the film in the edit? You talked about building towards this one moment but how do you go from all of this footage to an idea of the shape?

GR: I never watch my footage while I’m filming. But I film everything myself so my memory is very strong, what works or what doesn’t work. When I start editing, I give all the material to my assistant, and he logs the whole film: the doctor, the migrants, the night, the day, the island. I pick out the moments that I remember are important. I don’t look at all the footage. I just take out the scenes that I remember.

[clickToTweet tweet=”The film was all built around arriving at a point where I could show the tragedy.” quote=”The film was all built around arriving at a point where I could show the tragedy.”]

It’s like if I ask you what happened to you in the last year of your life. You don’t remember every single day. You remember a few moments. So I work with the moments that the memory is somehow suggesting to me to bring it out. The film was all built around arriving at a point where I could show the tragedy. This was somehow like a memorial to the death. It was like, “not yet, not yet.” It was important to develop all the stories: the kids, the doctor, the migrants. Everything had to have a complete narration and there were inter-cut stories. I had to follow also the growing of the story to arrive at this moment. But not only arriving at this moment, but to be able to leave from that moment.

[clickToTweet tweet=”I try not to intellectualize too much. There’s always a danger when you intellectualize.” quote=”I try not to intellectualize too much. There’s always a danger when you intellectualize.”]

7R: When you figure out where to put it, is that just instinct? Or is it more intellecutlized.

GR: I try not to intellectualize too much. There’s always a danger when you intellectualize. It’s more like following instinct, following certain sensations and moods. If you intellectualize too much, it becomes cold. It becomes distant.

[clickToTweet tweet=”I never look for footage. I remember the footage that I shot. I know what’s good and not good. ” quote=”I never look for footage. I remember the footage that I shot. I know what’s good and not good.”]

7R: Are you able to find enough of the moments you remember to give the pacing you want? Or do you have to go back and look at your old footage to find ways of connecting…

GR: I never look for footage. I remember the footage that I shot. I know what’s good and not good. So I never really go back desperate to look at the footage. When I do that, it means there’s something extremely wrong in the editing.

Usually, in the editing, if you feel like you’re stuck, and there’s a problem, the problem is never where you realize the problem is. It’s before. So you have to go back. Sometimes, you destroy everything and start from scratch. This I did many times. You arrive at a dead end. It doesn’t go anywhere. So I erase everything and start from scratch until you find the right pace.

[clickToTweet tweet=”In the editing, if you’re stuck, the problem is never where you realize the problem is. It’s before.” quote=”In the editing, if you feel like you’re stuck, the problem is never where you realize the problem is. It’s before.”]

7R: So how do you know when it’s done?

GR: Usually, you know when a film is done when there are scenes that you thought were going to be part of the film that are out, and that somehow everything is necessary in its place. You do many screenings. You watch it. You change things. Then, there’s a moment when you feel like everything is in harmony, like a symphony.

It’s like composing a piece of score. You have to have an emotional sensitivity when you edit. You have to bring everything to the present tense and forget that you’re the only one that experienced it.

[clickToTweet tweet=”It’s like composing a piece of score. You have to have an emotional sensitivity when you edit. ” quote=”It’s like composing a piece of score. You have to have an emotional sensitivity when you edit. “]

You always have to create the right space between notes, and every note belongs to the next note. Every character has to belong to the next character. Every story has to go to the next story. There’s a gap between stories, which is a gap between notes, and this is very important to fill, the silence between notes, the space between characters, the space between scenes, the note of quietness. You abandon a character and go back to another one. And then you go back to other stories.

Read more: Gianfranco Rosi on designing the sound, developing the aesthetic, and finding the title for Fire at Sea >>

Read more: Frederick Wiseman talks editing In Jackson Heights >>

[/wcm_restrict]