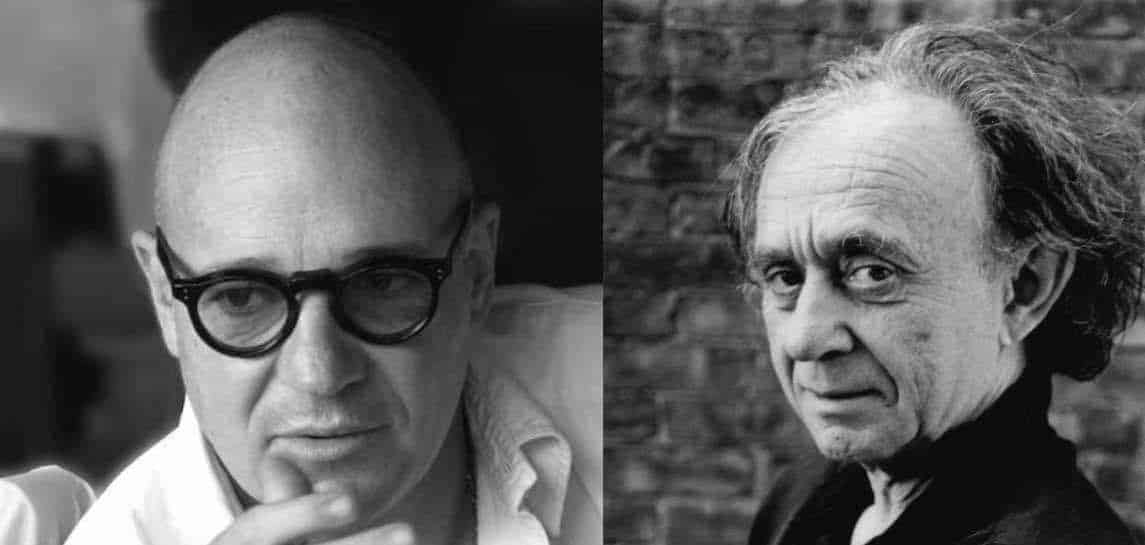

Every documentarian has a unique approach to filmmaking, but you might not expect that Frederick Wiseman and Gianfranco Rosi often have polar opposite approaches to making their films. Based on two interviews with each documentarian, we break down their many points of difference, and a few similarities, in their approaches.

When I recently interviewed Gianfranco Rosi about the making of Fire at Sea and editing the film, I found myself constantly thinking about how Frederick Wiseman shot and edited In Jackson Heights and National Gallery: in many ways, their approaches couldn’t be more different. Here’s a look at how these masters approach documentary filmmaking, often in opposing ways.

Gianfranco Rosi and Frederick Wiseman on Collecting footage

Although Frederick Wiseman only spends 4-6 weeks shooting his films, he regularly compiles at least as much, if not double, the amount of of footage that Rosi collected over the year and a half he spent making Fire at Sea. Both directors regularly operate the camera on their films. But while Wiseman won’t wrap the edit on his film before rewatching all his footage, Rosi never watches the footage he shoots. Wiseman edits all of his films himself, but Rosi uses an editor, whom he tasks with sorting through and watching his footage.

When I think the film is finished, I go back and look at all the — in the case of National Gallery, all 170 hours — footage all over again to make sure that there’s nothing that I rejected that has become important as a result of the choices that I’ve made. – Frederick Wiseman

When I start editing, I give all the material to my assistant, and he logs the whole film: the doctor, the migrants, the night, the day, the island. I pick out the moments that I remember are important. I don’t look at all the footage.I just take out the scenes that I remember. – Gianfranco Rosi

Wiseman, on the other hand, focusses all of his attention on editing once he starts, and he works alone.

I have to be completely absorbed in it. I literally don’t do much else for months, because you can’t edit, or at least I can’t edit these kinds of movies with the back of my hand. I have to really eat, sleep, and drink the material. Usually, when I’m working on a sequence, I’ll work on it until it’s done. Sometimes, I’ll come back to it. I often will change it, when I look at it a day later or a week later, because I don’t think the rhythm works, or it’s too long or too short. Usually, I get it close to final form in the first, not necessarily the first go, but the first intensive period of concentration on it. The first go may last two days. – Frederick Wiseman

Figuring out where to put the camera: Gianfranco Rosi vs. Frederick Wiseman

While Rosi considers his films to be portraits, Wiseman’s films focus on institutions. This greatly affects how they approach shooting their subjects. For Rosi, figuring out where to put the camera, at what distance to shoot his subjects is crucial for the emotional content of the film. For Wiseman, it’s about capturing everything that’s happening and giving himself enough footage to work with to play with the rhythms of the film in the edit.

Where to put the camera in relation to the subjects is very important. This is a very tricky thing when you do documentaries. The distance you find is where you find the truth of what you’re doing. It’s a very important element for me: the distance between the camera and the subject, the right angle, the right height, the right point of view, the emotional point of view of the character. It’s not a rational thing, but it’s something you have to discover every time. – Gianfranco Rosi

When describing shooting a scene with a group of musicians in the park for In Jackson Heights, Wiseman spoke in very practical terms about capturing all that was going on and getting what he needs for the edit:

If you started doing closeups, it’d be very hard to sync. You can do it sometimes, but it’d be very hard to sync up the hand movements on the instruments with a different song. Sometimes, you can fake it, but it’s very hard to do that. I think it’s a better shot, wide, because you see the whole group, and you see the group in relation to the people that are watching. – Frederick Wiseman

To read the rest of the comparison between how Gianfranco Rosi and Frederick Wiseman approach their work, based on our interviews, purchase a copy of the ebook In Their Own Words: Documentary Masters Vol. 1 here. The book also contains three interviews with Wiseman (on National Gallery, In Jackson Heights, and Ex Libris) and a pair of interviews with Rosi.

[wcm_restrict]

One thing they both do agree on is the usefulness of wide shots, although they both like them for different reasons.

I wanted to create a stillness of narration. Everything was on the tripod. I didn’t want to have a shaking camera that moves around. I didn’t want to have the sense of improvising. I let things happen in front of the camera. Very rarely, I do a pan, unless something happens here I have to cover something else. I wanted always within this frame to be able to tell a story beginning middle and end. I wanted to create this sense of long shots, of long sequences, which is like life. Through the camera and sound, I wanted to give the film a narrative thickness. – Gianfranco Rosi

For Wiseman, wide shots are often about making sure you don’t miss the action: in nonfiction filmmaking, you only get one shot, and Wiseman wants to make sure he captures what he sees. This is especially the case for shooting dance, which he doesn’t like to break up in the edit for much the same reason Rosi likes long shots and long sequences:

The best way to shoot dance was with a wide shot, because you see everything. I’d seen a lot of dance films where the filmmaker used the dance in the service of his own film purposes. I think the reverse should be true. The filming should be at the service of the dance. You don’t have a zoom in your eye, [but in] a lot of dance films you see elbows, faces, toes. You don’t see the partnering. You don’t see the whole body. – Frederick Wiseman

Although Rosi only pans when absolutely necessary, Wiseman absolutely abhors pans. He completely avoided them in National Gallery:

There are no panning shots, because I don’t like panning shots. But there are lots of, in some of the story paintings, like Holbein’s The Ambassadors, you see closeups of different parts of the paintings. I cut those close-ups to be linked to what the guide was saying about the painting. But at the same time, you’re both seeing the whole painting, but you’re seeing the painting in serial form, which is different from the way you look at a painting in a gallery. But [it’s] similar to the way you look at a sequence in a movie, or read a chapter of a novel, or the whole novel. – Frederick Wiseman

Anticipating the edit or not anticipating the edit? Gianfranco Rosi vs. Frederick Wiseman

For Rosi, the most important footage he shoots is the stuff he remembers months later, the way you remember important events in a year of your life but not everything that happens in your life.

It’s like if I ask you what happened to you in the last year of your life. You don’t remember every single day. You remember a few moments. So I work with the moments that the memory is somehow suggesting to me to bring it out. – Gianfranco Rosi

For Wiseman, on the other hand, years of editing his own films has changed the way he approaches capturing footage so that he knows he’ll have enough to work with in the edit to achieve the effect he wants.

I try to anticipate, in a general way, what I’m going to need in the editing. I shot hundreds of shots of streets, street corners, schools — really anything that interests me, knowing that the film was going to be made up of different events and different parts of Jackson Heights and knowing that I would need transitions, but also being aware of the fact that the cutaways serve other purposes, like giving a sense of the nature of the businesses, street activity, who was walking on the street, the clothes that they were wearing, businesses, street vendors, traffic signals, buses, cars. I knew I needed all that, and I needed a lot of it, not only for choice, but since the events aren’t staged.

You just accumulate stuff, knowing some of it is going to be short and some of it is going to be long. When we’re shooting, we always try to do it so, for example, a car goes in and out of frame. But I may need a 60 frame shot when I’m editing, and it may take 97 frames for the car to go in and out of frame. So that may be OK depending on what else is going on, or I may have to cut to another car. But then it’s a question of the direction the cars are going in, the speed, so that the rhythm of the shots that are cut together feels like it works together. – Frederick Wiseman

Similarly, when shooting In Jackson Heights, Wiseman knew early on that he would need many shots of the subway, at different times of day and at different angles. It wasn’t until the edit that he realised exactly why.

These shots servce the literal purpose of indicating the subway goes there. It serves the editorial purpose of giving the suggestion of moving around from one part of the neighbourhood to another. Also, it provides the purpose similar to a lot of the other uses of cutaways, which is the passage of time, pauses, a little bit of rest, and also gives it a sense of the sounds you hear in the street. – Frederick Wiseman

Should you intellectualize the editing process?

Although both filmmakers have decades of experience making films, they have completely different approaches to how to think about the editing process.

I try not to intellectualize too much. There’s always a danger when you intellectualize. It’s more like following instinct, following certain sensations and moods. – Gianfranco Rosi

For Wiseman, however, editing is an extremely intellectual process with a dash of intuition. Working out the structure involves thinking about the film in ”two paths: the literal and the abstract.”

The structure of the movie emerges from where they meet. In any movie, I’m trying to work out a dramatic narrative, so I have to think about the relationship between the talk sequences and the music sequences or the so-called action sequences, and how they fit together, both visually and thematically. A lot of the cutting in Jackson Heights was sort of at right angles, in the sense that I tried to cut it in a way so that nothing would be predictable: the next sequence was always a surprise and lifted you out of the previous sequence. After a long talk sequence, there might be some music.

Editing requires a combination of trying to be very rational and also following your associations and your intuitions. The latter are just as important as the former. I’ve learned over the years to pay attention to the things at the margin of my head, and they’re just as important in helping me solve a problem as the more deductive aspects. All the deductive aspects are important because at the end, I have to be able to explain to myself why each shot is there, and that is a more rational process than the way I may have sometimes arrived at the order. – Frederick Wiseman

In fact, Wiseman has to be able to justify to himself why each scene is where it is in the film in order to be satisfied with the edit:

I have to have a reason. I start off with no point of view toward the material, no thesis. The film emerges as a consequence of the experience of being at the place, and thinking more specifically about it, in the course of the editing, in making the choices.

I like to keep an open mind — or at least I think I have an open mind — during the shooting and during the editing, so the final film is a response to the experience, to what I’ve learned as a consequence of the experience, rather than the imposition of per-conceived views.

There are always new ideas, or ideas new to me are being stimulated, by the editing of individual sequences, and then making some judgement about the consequences of putting them in a particular order, and trying out different orders. One of the ways I know the film is finished is that I have to be able to explain it, with words, why I’ve done what I’ve done, why each cut is there, what its relationship is to what is before and after, etc. – Frederick Wiseman

When Wiseman was editing National Gallery, it took him more than a year.

For National Gallery, it took about 13 months. I start off by looking at all the rushes, making notes about them — that may have taken, in the case of National Gallery, a couple of months. I then edit the sequences that I think I might use in the film. When I’ve edited all of those, after that first go round, I put aside about 50% of the material. Then, I edit the sequences that I think might be in the final film. It’s only when I’ve edited all of those so-called “candidate” sequences, in close to final form, that I begin to work on the structure.

At that point, I can work out the first assembly rather quickly, because all the sequences I think I might use are in decent shape. That first assembly comes out to be usually 30 or 40 minutes longer than the final film. After that, I work on the internal rhythm within the sequences and the external rhythm in the way the sequences are linked. I change things around quite a bit. Then, when I think the film is finished, I go back and look at all the — in the case of National Gallery, all 170 hours — footage all over again to make sure that there’s nothing that I rejected that has become important as a result of the choices that I’ve made. – Frederick Wiseman

Rosi, on the other hand, knows that a film is done much more on a gut level:

Usually, you know when a film is done when there are scenes that you thought were going to be part of the film that are out, and that somehow everything is necessary in its place. You do many screenings. You watch it. You change things. Then, there’s a moment when you feel like everything is in harmony, like a symphony.

It’s like composing a piece of score. You have to have an emotional sensitivity when you edit. You have to bring everything to the present tense and forget that you’re the only one that experienced it.

You always have to create the right space between notes, and every note belongs to the next note. Every character has to belong to the next character. Every story has to go to the next story. There’s a gap between stories, which is a gap between notes, and this is very important to fill, the silence between notes, the space between characters, the space between scenes, the note of quietness. You abandon a character and go back to another one. And then you go back to other stories. – Gianfranco Rosi

How do you fix problems in the edit?

Both Rosi and Wiseman agree that if you find a problem in the edit, it usually means there’s a problem much earlier on in the film, and you may need to reassemble it from scratch. But while Rosi works exclusively with the sequences he’s already decided should potentially be in the film, Wiseman will often go completely back to the drawing board, revisiting old footage to see if he should swap sequences.

Usually, in the editing, if you feel like you’re stuck, and there’s a problem, the problem is never where you realize the problem is. It’s before. So you have to go back. Sometimes, you destroy everything and start from scratch. This I did many times. You arrive at a dead end. It doesn’t go anywhere. So I erase everything and start from scratch until you find the right pace. – Gianfranco Rosi

Wiseman also plays around with the order of his sequences, but he has to have a reason for why each scene is where it is, and he’ll often go back to his footage and discover something he’s ignored really should be in the film.

I might start out the film one way, and then a week later decide that I don’t think that works. I change it to something else, and then by changing it to something else, it has consequences for what follows. Sometimes, you cut a sequence with a beginning, middle, and an end. But then, when you put it in relation to other sequences, the middle of it may be better covered in another sequence, so out goes the middle. Or it may feel too long or too short depending on what it’s in relation to. Or you may discover another theme further on so you want to add something. Or you may see the same thing expressed better [elsewhere] so you take something out. – Frederick Wiseman

Read more: Gianfranco Rosi talks Fire at Sea: the making of (Part 1) >>

Read more: Gianfranco Rosi talks Fire at Sea: editing (Part 2) >>

Read more: Frederick Wiseman talks National Gallery >>

Read more: Frederick Wiseman talks In Jackson Heights >>

[/wcm_restrict]