Cinematographer Joshua James Richards talks adapting to a director’s vision and creating a sense of place in God’s Own Country and The Rider. This is an excerpt from our ebook God’s Own Country: A Special Issue, which is available for purchase here.

Chloé Zhao’s The Rider and Francis Lee’s God’s Own Country are two of this year’s most celebrated films — and two of Seventh Row’s favourites. Sensual and visually stunning, both owe a significant part of their success to the work of Joshua James Richards, the director of photography they share. Yet the process of making the films could not have been more different. While God’s Own Country rarely departed from Lee’s script, Zhao was more interested in capturing unexpected moments.

For his adaptability and vivid sense of realism, and with two major films already under his belt, Joshua James Richards is a talent to keep an eye out for. Seventh Row talked with the British cinematographer about adapting to different working methods, bringing out sensuality and sense of place, and supporting a director’s vision.

Seventh Row (7R): How did you create the look of God’s Own Country? Did you collaborate a lot with director Francis Lee?

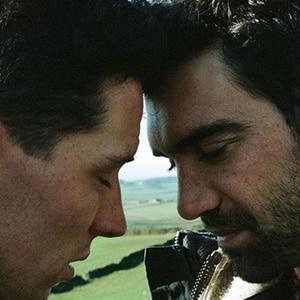

Joshua James Richards: It started with just reading the script. The scenes were so vivid and well described. The world of Johnny (Josh O’Connor) – one of vomit and piss and shit – was all on the page. I had a sort of visceral feeling whilst reading the script, before I even spoke with Francis. I also really responded to the candidness and intimacy that develops between him and Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu), because it was rendered in such a visual way. The dialogue was quite sparse, which suited the world of the film and the characters, in a place I kind of knew quite well anyway, coming from Cornwall.

After talking with Francis, I did about a month of preparations with him. That included a lot of pretty hardcore, long sessions between me and him, and a lot of me just sort of picking his brain, because Francis was coming from something more of an actors’ place. We had to try to get a mutual language going, which was so important because that ran throughout the remainder of the shoot. We didn’t have to talk much once we were on set, just because there was that trust that had formed before. We knew exactly where he was coming from, exactly what he wanted.

7R: Was it very different from the way you worked with Chloé Zhao on The Rider? You had already worked with her on her previous film, Songs my Brothers Taught Me (2015).

Joshua James Richards: It was. The process couldn’t have been more different, really. For one, Chloé’s process for The Rider: there was a script, but it was just a sort of 40-page throughline of a story. She was using real people in their real surroundings, and she was embracing that. As a result, she was very fluid and organic in her approach. There was never marks for the camera or for the cowboys to hear. The camera would always be reacting to them, rather than the other way around. That created a really interesting atmosphere, possibilities and accidents. I personally love to work that way. It’s so exciting.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘The world of Johnny (Josh O’Connor) – one of vomit and piss and shit – was all on the page.'” quote=”‘The world of Johnny (Josh O’Connor) – one of vomit and piss and shit – was all on the page.'”]

For God’s Own Country, Francis was very exact and quite rigidly followed the script. The lines that they speak in the film are the exact lines from the page, and there’s no straying from that. We shot on a real farm, a real part of Yorkshire where Francis grew up, so he knew that place like the back of his hand. It was a more conventional approach in terms of production designers and team — the kind you expect on a film on a quite tight budget. You’re there to support the director best you can, to support his vision.

On The Rider, it involved more supporting Chloé in capturing something that was fleeting. And you may not capture it! You don’t have the sort of same window! Yet she was able to work her way around that. She removes her ego. She just lets life happen. Hopefully, the cameras are there to capture it in a cinematic way.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘It’s a place that encages you. I tried to convey it in the film through Johnny’s point of view.'” quote=”‘It’s a place that encages you. I tried to convey it in the film through Johnny’s point of view.'”]

7R: You were familiar with the area where God’s Own Country was shot but maybe less so with that of The Rider. Yet both films have a very strong sense of place. How did you work to bring out this sense of the location on screen for both films?

Joshua James Richards: For The Rider, I had the experience of Songs my Brothers Taught Me. That was a particularly special one for me, because from an early age, I had been reading about that part of America, and playing Indians, etc… For whatever reasons, I read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee when I was a young teenager. I’ve always kind of dreamt about that landscape. So when the time came to do The Rider, I’d been back and forth there with Chloé, over a five year period. I was so excited to get out there. After Songs, I wasn’t really satisfied with that film visually, and I felt we could have made more use of the landscape telling the story. That’s why The Rider was so satisfying, because I could get my teeth into that.

In God’s Own Country, there’s a very different approach to the landscape. That’s because when describing growing up there as a young lad, Francis said that your face is always down at the ground. You’re just looking at the mud; you’re not really appreciating the beauty of it when you’re from there. It’s a place that kind of encages you. I find that very interesting visually, and I tried to convey it in the film through Johnny’s point of view. Then, that landscape opens up when Gheorghe starts to unravel his heart.

To read the rest of the interview with cinematographer Joshua James Richards, purchase a copy of the ebook God’s Own Country: A Special Issue here.

[wcm_restrict]

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Both directors are more interested in a cinema of emotions than they are in one of narrative.'” quote=”‘Both directors are more interested in a cinema of emotions than they are in one of narrative.'”]

7R: Something else that the films have in common is their focus on sensuality. God’s Own Country is about the attraction between two men. But The Rider is also about the sensations particular to that lifestyle and the injuries it can entail. How did you bring that sensuality to the film?

JJR: That’s something I respond to when I read the script, on a personal level — in the scripts that I read and in the cinema that I watch. In the films that I’ve been influenced by, there is that attempt to capture the connection between human beings. Or even, in the case of The Rider, human beings and animals — the relationship between Brady (Brady Jandreau) and the horse isn’t something I can remember seeing anywhere else in the same way. They’re two directors who have allowed me to do that.

But I think that what the films really have in common is that they required me to build a level of trust with the cast. In God’s Own Country, I was real good mates with Alec and Josh by the end, and they were doing things in that film that I thought were very brave, and should be handled very sensitively. There was a sort of relationship forming off camera, as well, so that they were happy for me to be there in the room with them. I feel like we’re all kind of doing it together.

With Brady, I’d known him for two years by the time we shot. He’s very careful about who he’s letting in his world with him. We had built a trust by the time we shot, and I could get the camera up close and intimate. Also, they’re two films that explore a world through a character’s very subjective gaze. You’re really experiencing the badlands through Brady’s world and the way that he navigates through that. This, coupled with the themes of the film that me and Chloé discussed, you build a visual language from there. But I think it’s natural that it would feel intimate and up close, because in both films, we’re telling the story from the inside out.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘On set, it’s about protecting the director and the atmosphere that he or she wants to create.'” quote=”‘On set, it’s about protecting the director and the atmosphere that he or she wants to create.'”]

You’ve got a director, as with God’s Own Country, who’s literally from that place, telling an incredibly personal story. And then, you’ve got Chloé, who’s allowing these cowboys to tell their own story. In both cases, we wonder, “How do we do that?” How do we put the camera in there and let the audience feel that? Because both directors are more interested in a cinema of emotions and feeling than they are in one of narrative… I find that difficult to convey from a distance. In both films, it’s done with a longer lens to get close to someone. I made a similar lens choice for both films, actually — with wider angles and getting a little bit closer. Perhaps too close in some instances!

With God’s Own Country, that was a more typical approach to filmmaking. Whereas in The Rider, although Chloé had really specific ideas about how she wanted the film to look, a lot just happened naturally. It was more instinctive.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘It’s the DP’s job to create the correct environment on set — as well as being a technician.'” quote=”‘It’s the DP’s job to create the correct environment on set — as well as being a technician.'”]

7R: Can you cite some of your influences?

JJR: Regarding The Rider, I actually did grow up watching a hell of a lot of westerns, so I was really excited about the opportunity to show that kind of iconography. I was drawing from westerns, but of course Néstor Almendros’ work on Days of Heaven (1978) was always in my mind.

I really respond to Jacques Audiard’s stuff, particularly in A Prophet (2009), and we watched that film before God’s Own Country. Again, you won’t get a more singular point of view than that film. Andrea Arnold has always been an influence, and Robbie Ryan’s stuff has always inspired me. The list could go on and on…

7R: When you work on a film, you’re obviously more than a technician, because you work closely with the director. But do you also engage with the actors on a personal level? Or do you go by the director to see what they’re comfortable with?

JJR: That always has to come from the director, I think. They are really interesting films to compare, in that sense. When I’m on set, it’s completely about protecting the director and the atmosphere that he or she wants to create. And that’s what you respect. But then, in God’s Own Country, I sensed that Francis would prefer for Josh to have a bit more space since, as an actor, that’s how he likes to work — just to kind of immerse himself in that world. He needed a little more isolation, I suppose. With Alec, we would hang out a lot. This film was our film. It was a journey, and we were all on it together. Sometimes a bit of morale is very important, and it gets you through, especially with films that are kind of personal.

With The Rider, I really can’t imagine anyone else being able to make it —certainly not how Chloé did. She would create an environment, and then, put the camera in that. There was no point in trying to shoot these cowboys as a conventional film crew, where everyone sticks to their role just as their job. They’re not actors. They’re not used to that world. If you’re not interacting with them as human beings, then it all falls apart pretty quickly. They were very comfortable making the movie with their friends, and I felt the same way. That was Chloé’s preference. That was what she wanted.

But then there would be other times where she would say, “Josh, take a step back. I need to talk to Brady alone,” and then I just had to set up the camera. There are intimate scenes in that film, as well, where it would just be Chloé and Brady alone, and you just have to be there and support that. But I do think it’s the cinematographer’s job to create the sort of correct environment on set — as well as just being a technician.

[/wcm_restrict]

Read the rest of our ebook on Francis Lee’s God’s Own Country >>

Read more about great queer cinema…

Call Me by Your Name

Read Call Me by Your Name: A Special Issue, a collection of essays through which you can relive Luca Guadagnino’s swoon-worthy summer tale.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Read our ebook Portraits of resistance: The cinema of Céline Sciamma, the first book ever written about Sciamma.

God’s Own Country

Read God’s Own Country: A Special Issue, the ultimate ebook companion to this gorgeous love story.

In our Behind The Lens series, we talk to some of the best cinematographers working today about their process, their craft, and how they collaborate with directors. We’ve talked to Jakob Ihre twice about his working relationship with Norwegian filmmaker Joachim Trier for our Special Issues on each of the films — first for Louder Than Bombs and then for Thelma. We interviewed Tom Townend about the many hats he wore as the cinematographer for You Were Never Really Here for our Special Issue on the film; he had some amazing behind-the-scenes stories. And we talked to Magnus Jonck about his work on Lean on Pete for our Special Issue on the film.