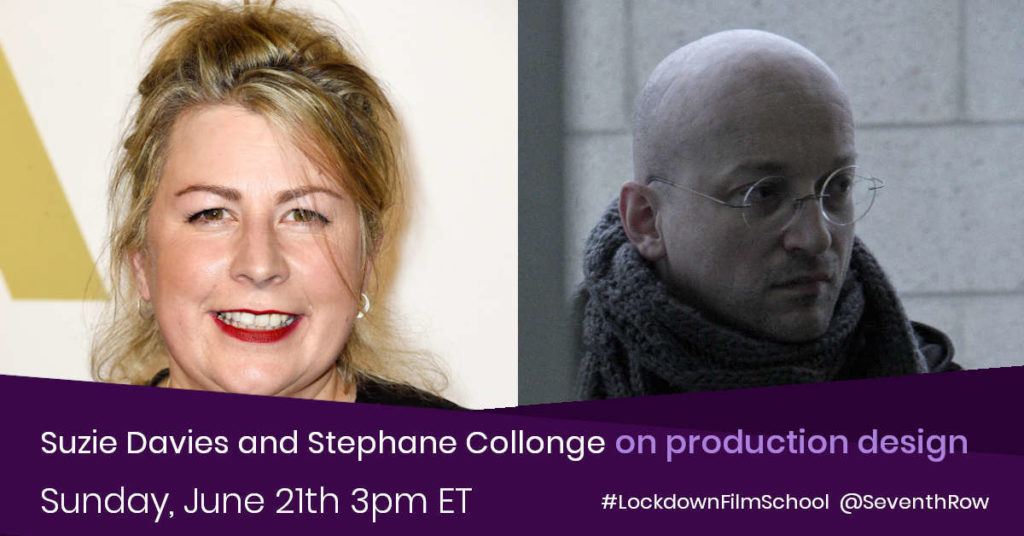

On Chesil Beach production designer Suzie Davies discusses researching period, creating environments that contrast with the film’s characters, and how different her process is when working with Mike Leigh. Read the rest of our On Chesil Beach Special Issue here.

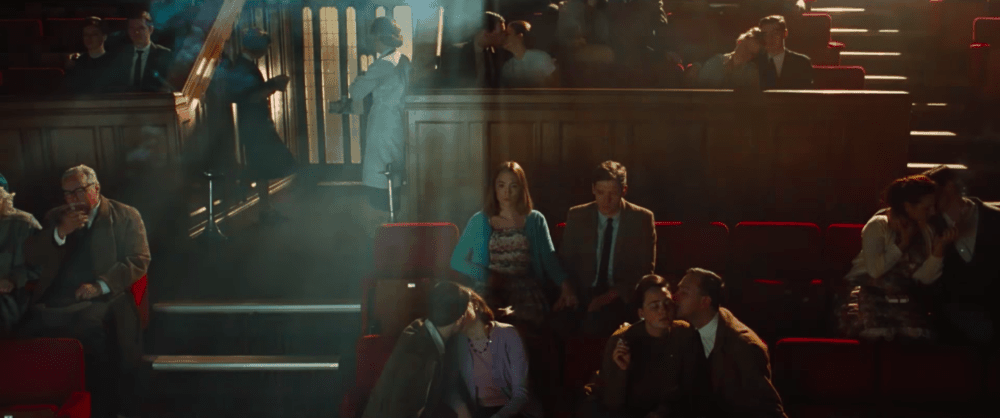

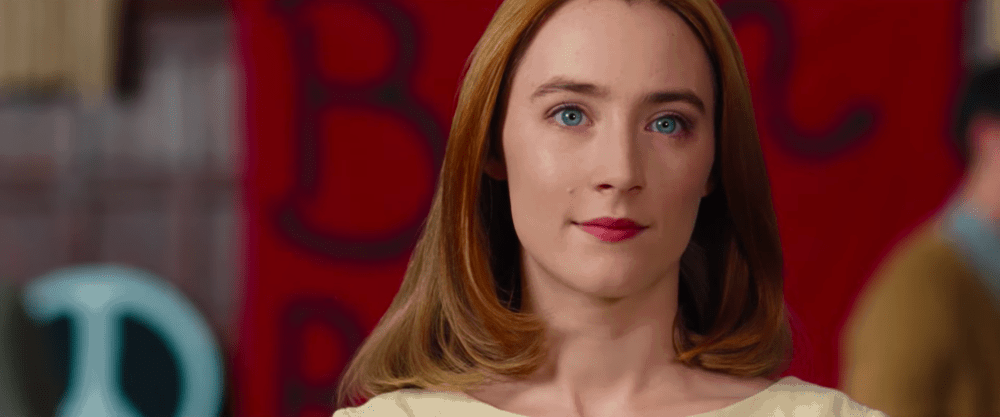

It’s Britain in 1962, and nobody talks about sex. A young couple — Florence Ponting (Saoirse Ronan) and Edward Mayhew (Billy Howle) — is left alone in a hotel room, expected to do something they know nothing about. Their courtship was sweet, loving, idyllic even — but everything in On Chesil Beach comes down to one scene, in one room. The trip from the dinner table to the bed, although only a few metres long, seem like a treacherous journey. There’s no avoiding sex, but it’s a terrifying leap into the unknown.

Listen to our podcast on On Chesil Beach and Normal People

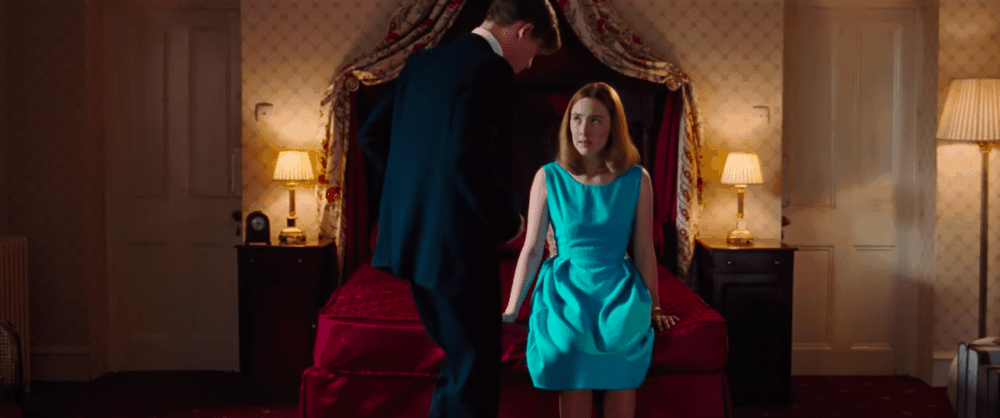

Production designer Suzie Davies achieves a delicate balance: her sets are period accurate and naturalistic but they’re also expressive beyond plain practicality. She brings out the contrast between Florence’s upper middle-class upbringing and Edward’s poorer, more ramshackle country home. Their home environments are shaped by their parents and the circumstances they were born into; these young people long to break free to find a home that they themselves can shape. Instead, they find themselves in the cold, neutral environment of the hotel room, where the colours oppress and displace them. Convention dictates that they are supposed to be here — it’s just the natural order of things. But neither feel like they fit in.

I talked to Davies about researching period, creating environments that specifically don’t reflect the characters, and how vastly different her process is when working with Mike Leigh.

7R: Every production designer has their own process which changes depending on what film you’re working on and who you’re working with. Can you describe what your process usually looks like and how you adapted it for this particular project?

Suzie Davies: I do have a process. The only time it changes is when I work for Mike [Leigh].

For a traditional film like On Chesil Beach, as I’m reading the script for the first time, I write down my initial thoughts. Whether that’s artists, a particular period, any colours, any sound… it’s a bit of everything, really. I write it down straight away, because I’ve realised over time that, quite often, my original thoughts are my strongest ones, and I’ll end up coming back to them. So it’s literally scribbling my notes on the back of a fag packet.

I’ll catch up with my set decorator, Charlotte Watts, and we start bouncing ideas off of each other. Sometimes we’ve gone away and researched together on an away trip, for a weekend or a couple of days, like we did on a film called The Zookeeper’s Wife (2017). We wanted to look at some European zoos so we went off to Antwerp. It’s great to inhabit the world as much as you can. Obviously, with period films, it’s a bit more difficult, but it’s the case of doing the research.

Then it’s about collaborating with [director] Dominic [Cooke], seeing where we’re at, and developing things organically. On this film, we did a lot of recceing. That’s a good time to get into the director’s mindset, because ultimately, it’s the director who needs to be the one telling the story. I’m there to complement — maybe enhance, if I’m lucky — but on the whole, complement. Sometimes, you can get too many people trying to direct one story, so I find the recces, when it’s just me, the location manager, and the director, to be really helpful. You’re just sat in the back of the car going between locations. I liken it to getting into his brain by osmosis. Sitting and talking about the project from every different angle helps you get into the mindset of what he wants.

As you get closer and closer to filming, you’ll have less time with the director, so you can feel pretty confident that you can do any changes or any adaptations you need to because you’ve got the shorthand already.

7R: What stood out to you when you first read the script for On Chesil Beach?

Suzie Davies: Chesil Beach is such a famous beach; I liked that idea that it was just on its own, kind of isolated.

The other thing was that we never see these two characters in their own environment. They haven’t found their environment yet. They’re still growing up. Quite often, you create worlds for characters that you really know, environments that enhance their character. But we were never in their world; we’re at their parents’ house, or where they work. That was quite a strong feeling for me, that they never did feel comfortable in their environment.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘We never see these two characters in their own environment. They haven’t found it yet. They’re still growing up.'” quote=”‘We never see these two characters in their own environment. They haven’t found it yet. They’re still growing up.'”]

I realised it had to be a very low key and quiet piece, rather than something like Mr. Turner, where it’s over the top and bold and brash. This was very, very quiet, very gentle, very sensible.

I liked how there was a battle going on amongst the beautiful trees. There’s a darkness within the gentle layer on top. It’s about opposing forces, the chaos and the order of their lives in that era, the suppressed feel at the beginning of the ‘60s.

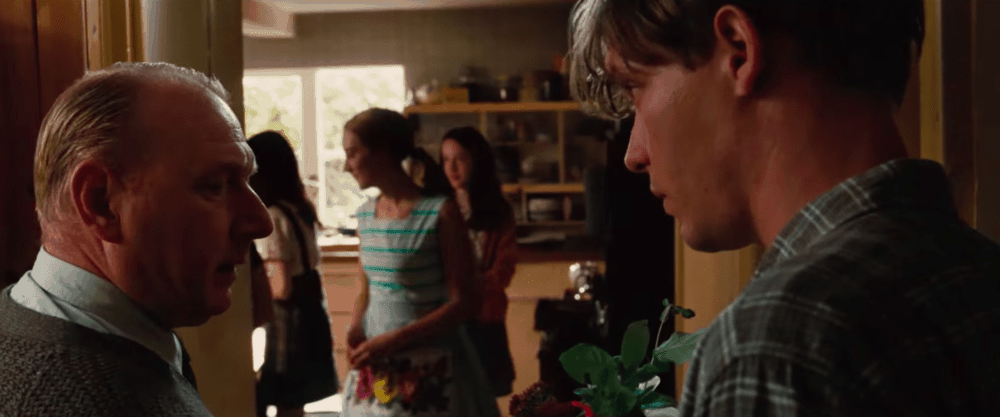

We weren’t going to be looking at a bucolic, romantic England, although there are elements of that. It wasn’t necessarily better back then. It was difficult. The beautiful house that the Mayhews live in is a bit over the top: everything’s messy and busy and busting at the seams. The outside is coming inside, and it’s chaotic. We still see how difficult it is to live in that house.

The Pontings’ house was very regimented and sort of airless, with hard, shiny surfaces — nothing was alive there. It was quite fun to play those opposites.

7R: They’re both from two very different worlds that come together in that hotel room.

Suzie Davies: The hotel room was quite fun because that’s still not their environment. We changed the colour scheme a bit and went slightly over-the-top, dressing it so that it was all very regimented, very symmetrical. It’s all about that bed. We just built it, and built and built and built, so that that was their main aim. There was a pressure on them.

We’d chatted with Dominic to work out why they went to that hotel, and we reckon it’s because their parents went there. It’s really old and fuddy duddy. When you see them walk through the reception, they’re the youngest people there. We get that one of their parents probably had their honeymoon there, and we took the backstory from that.

All the colours were slightly off. You could see where it had been done up in one bit because this was post-war. They probably did it up in the ‘40s, and now we’re in 1962, and it probably wasn’t even done up correctly.

7R: What does the physical element of your prep look like? Do you make lookbooks or mood boards? How do you communicate your ideas to the rest of the crew?

Suzie Davies: On every project, after that first time I read the script, the next thing I do is start making images, putting them on a photostream, and sharing them with everyone. They’re really broad brushstrokes of my inspirations. That’s shared with all the Heads of Department (HoDs) and the whole of my department. Then we start honing them down and grabbing and taking away and manipulating parts.

Once you know what your design rules are or what your colour palette is, you have to stick to it. Everyone in the department will have a booklet of the colour palette that we’re using. On this film, there’s probably 12 colours that we used if we need a poster made, or we need to choose the colour of a car, or anything, it all comes from the same language.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘Everyone in the department will have a booklet of the colour palette that we’re using. On this film, we probably used 12 colours.'” quote=”‘Everyone in the department will have a booklet of the colour palette that we’re using. On this film, we probably used 12 colours.'”]

As soon as we get any drawing for the set build, we make a little white card model. That enables the production team to work out what we’re doing, because a lot of people can’t necessarily read a pencil drawing. I quite often do a walkthrough on SketchUp, as well, that we can send to directors so they can walk through a fake animated environment. It’s not necessarily rendered or with any colours yet, just a white room, so we know the sizes and shape of what we’re talking about. That can really help because the DoP can say, “It’d be great if we could float this wall,” or “Can you give me a camera trap here?”. All those decisions can be made well in advance, before you’ve spent any money building the set.

Quite often, the set decorator’s room is the best room to go into because she just hangs up swatches of fabric and wallpaper. If we like the idea of something we picked up from an antiques fair for a particular environment in the film, we just collect that stuff, so there’ll be a corner of the room for the Pontings and a little corner for the Mayhews. When Dominic — or anybody from the production — comes in to have a chat, they can get a feel of what we’re doing.

7R: How did you choose the colour palette for this film?

Suzie Davies: We liked the idea of using the same colours across the locations but in different ways: the Pontings is all flat colours, with no wallpaper, but the Mayhews is a lot of wallpaper.

I was also keen to make sure that we didn’t do those brash, bold ‘60s colours. We took it back to pastel-y, dirtier colours. We played a little bit with red, green, and cream at the beginning, but we ended up more with the blue, yellow, and brown.

We had this rule of restricting the palette of any green unless it’s of nature. Obviously, when we’re outside, we see green, and when we see plants, we see green. But we shouldn’t have any other green. That just adds to this airlessness and the fact that, when they’re outside in those green environments, that’s the only time when you think it’s all possible. You feel like nature is nurturing them.

7R: You said you didn’t use much red, so it’s even more striking that the bed sheets and the pillow in the hotel room are a deep red.

Suzie Davies: That red bed cover is made of an awful shiny fabric, and we had red draped around the bed, as well. That makes it jump out, and it works brilliantly with that blue dress. It feels garish, not comfortable at all.

7R: Even though they’re in a mid-size room, the journey to the bed seems quite daunting. How did you design the room to achieve that feeling of trepidation?

Suzie Davies: The room is slightly bigger than it would be in real life, just to make that distance a little bit more daunting.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘The red bed cover is made of an awful shiny fabric that just looks garish and very uncomfortable next to that blue dress.'” quote=”‘The red bed cover is made of an awful shiny fabric that just looks garish and very uncomfortable next to that blue dress.'”]

At one stage, we wondered if they should sit opposite each other and have the bed to the side of them. We played a little bit with thinking: where should the bed go? It ended up that it was better always being seen behind Florence’s shoulder, so the emphasis lay on her, and Edward could see the bed the whole way through. He’s constantly looking at the bed, and she’s pretending it’s not there.

7R: The film and that scene is all about them trying to find intimacy, but the room itself is quite open, without many small, intimate spaces.

Suzie Davies: Exactly. Even the fabric we used on the bed is shiny and slippery, so it’s not a comfortable looking bed. We got an old mattress and pulled bits out of it to make it really uncomfortable and baggy and awkward.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘He’s constantly looking at the bed, and she’s pretending it’s not there.'” quote=”‘He’s constantly looking at the bed, and she’s pretending it’s not there.'”]

All those shiny surfaces with a layer of dust on them were fun to take a little bit further. We’re in there so long that we’re able to go to town on the fine dressing. We would shave the carpet to get that feeling of it being worn away, and we put stains everywhere on it. It was good fun.

7R: The film is set in such an interesting time period, because it’s right on the precipice of a cultural shift in Britain, where things moved from strict tradition to a more modern way of thinking. How did you think about how to use those conflicting aesthetics?

Suzie Davies: The main part of the film is set in ‘62. We pick up with them in ‘59 when they start courting, but the environments in 1959 are actually post-war. So a lot of the carpets and the wallpapers and the fabrics are actually from the ‘30s or the ‘20s: you’ve come out of the war, and people weren’t changing or decorating their houses. They may have done a bit in the early ‘50s. You can do the research for 1962, but you’re actually researching the 50 years before that to try and create that depth and authenticity of that era.

That’s the same when we moved up again. We did ‘75 and 2007 at the end. It was about not being right on the nose. When we recreated Camden in the ‘70s, with his record shop, there are a couple of beats where we played with the graffiti of that particular year. But the rest of it, the cars and the clothes and the costumes, are on the money but not necessarily just of that year.

In 2007, we gave him a Volvo car that was 20 years old, because he wasn’t a wealthy man so he wouldn’t have bought a brand new car in the last 20 years. He’d still be driving a Volvo car forever.

7R: How much did you collaborate with DP Sean Bobbitt and costume designer Keith Madden to create a cohesive aesthetic?

Suzie Davies: Like any film, it’s a collaboration, so you have to make sure you’re all talking the same language during prep. Keith was often bringing in fabric, and we were checking how that would fit against our wallpaper.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘We would shave the carpet to get that feeling of it being worn away, and we put stains everywhere on it. It was good fun.'” quote=”‘We would shave the carpet to get that feeling of it being worn away, and we put stains everywhere on it. It was good fun.'”]

What was great with Dominic is that he made sure that all the HoDs really felt part of a team. We had a meeting somewhere in London where just the HoDs and Dominic had a read through of the script. We just alternated the parts for the whole script, and it was really great. I’d never done that before. Usually, you go to a read through with the actors — and we did do that, as well — but we did this a bit earlier. It was just the four of us and Dominic reading the script. You feel the rhythm of it, and you have a discussion at the end about the actual story — not necessarily from our own department’s point of view, but as a whole, holistic piece. It was great to feel that we’d all been there for that, and we all had the same starting point.

7R: As Dominic is a theatre director, the blocking in this film is very important. How set in stone was that early on? Did you choose or design sets to facilitate his pre-planned blocking, or was the process more organic than that?

Suzie Davies: It’s more organic. So for instance, the Mayhew’s house is a location that we went to. We discussed where the beds [in Edward’s twin sisters’ room] would be, because I had an idea that the twins would have their beds close together, which is actually taken from a German film called Amour Fou — this beautiful shot of the two girls with their beds pushed together. We had those discussions when we were on the recce, talking about whether these locations would work.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘Costume Designer Keith Madden was often bringing in fabric, and we would check how that would fit against our wallpaper.'” quote=”‘Costume Designer Keith Madden was often bringing in fabric, and we would check how that would fit against our wallpaper.'”]

One of the most important roles in the art department is the standby art director, who’s basically my eyes on set when they’re filming. I can’t often be on set all the time, because I may be busy prepping the next set: when they’re in the Mayhew’s country house, I was probably prepping the Ponting’s London house. So I’ll hand over the set to the standby art director.

On this film, it was so important, because it’s all about the composition of those scenes. Dominic could set a scene up and perhaps decide that the curtains need to be more royal-like, or a cello painting needs more paint on it. My standby art directors will enable all of that. It’s such a big task to compose a scene with the DoP, make sure it’s balanced, make sure that the prop guys have got the actual props, and the actors are happy with them. It’s all these nitty gritty things that you can’t really do until the day.

7R: When we talked to Keith Madden, he said that he views his process as a costume designer as almost similar to acting. Does that resonate with you?

Suzie Davies: Completely. The one moment I remember when that really came home to me was on Mr. Turner. We had Turner’s art studio dressed, and we were just doing fine dressing. I had the afternoon to tweak things, and I had this moment, where I stood there thinking, “How would Tim Spall playing Turner paint in this room?” So, for an afternoon, I painted in that studio. I chucked paint about, worked out where he would put his brushes, how he would sit and have a moment with one of his cats… It was really, really good fun.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘We had a meeting where just the Heads of Departments and director Dominic Cooke had a read through of the script. We alternated the parts, and it was really great. I’d never done that before.'” quote=”‘We had a meeting where just the Heads of Departments and director Dominic Cooke had a read through of the script. We alternated the parts, and it was really great. I’d never done that before.'”]

It’s great if you’ve had a chat with the actor, because the actor’s going to playing that character. I can imagine what I think they’ll be like, but ultimately, the person who’s saying those words is the actor. It’s great with Mike, because you get to meet the actors and chat about the world they live in. On other films, quite often, the actors don’t get a chance to see their environments until the day they’re shooting on it, so I always make sure I’m around to hand over the set to the director and the shooting crew and just hover to make sure that they feel comfortable in that environment. Otherwise, we can make any tweaks or changes.

7R: Did you talk to the actors on this film?

Suzie Davies: Not really. We spoke to them about all the hand props and their small props — but again, because it’s not their environment, I made sure I didn’t speak to them about their environments. And the actors playing their parents, I just didn’t get time. They literally turned up on the day. I just made sure that we were there on the day, handy to see if there were any tweaks to be made. But I know Dominic. Obviously, Dominic gets to speak to them, and I used him as the conduit for dressing sets, if I don’t get time with the actors.

Mike’s process is so indulgent in comparison. There’s not many other directors who can say, “I’m not going to tell you who’s in it, and what it’s about, just give me some money, and I’ll make you a great film.” There’s no script. But it works for him. and it works very well for him.

7R: On a Mike Leigh film, are all the sets built before his extensive rehearsals, or are they created based on what the actors come up with in rehearsal?

Suzie Davies: On Mr. Turner, I think he rehearsed for nine months beforehand. We were in the big, old Central St. Martins School of Arts in Hoburn, and we’d taken over a floor there. The actors had inhabited the rehearsal space like stage sets, with tape on the floor to delineate rooms. And then he had an AD team get bits of furniture like chairs and tables so they can inhabit a sort of fake kitchen or a fake studio. Mike can see how they’re doing, how often they go into this room or that room.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘Because the environment in the film is not that of the characters, I made sure I didn’t speak to the actors about it.'” quote=”‘Because the environment in the film is not that of the characters, I made sure I didn’t speak to the actors about it.'”]

We’ll get the sets ready a good two weeks before shooting starts, so Mike can then inhabit the world with the actors for a day, or a week, or a bit longer, depending on the weight of the scene that we’re filming. They rehearse on a fully dressed set with no shooting crew, just fine-tuning what they’ve rehearsed for the last nine months. Then, myself and Dick Pope, the DP, will turn up, and we’ll see what they’ve done in that day or two. Then it gets lit, and it gets shot.

Myself, the costume designer, and makeup will have what we call ‘actor’s surgeries’, where we’ll sit down the actors and talk about their characters. My first question is always, “If you needed a new kitchen table, where would your character get it from?” That answer can then inform me on the whole of their kitchen, because they’ll either say “I’d have a bespoke one made by the top person in tablemaking,” or “I’ll nick one,” or “I’ll go to homebase,” or “I’ll make it myself.” And you can then start building up this environment. You’re asking quite open questions.

We previously interviewed the production designer of Lean on Pete, Ryan Warren Smith, for our Special Issue on the film. Several directors have told us about the importance of choosing and designing the right locations, including Joachim Trier, Andrew Haigh, and Sally Potter. We analysed the importance of production design in The Party, Journey’s End, and Crimson Peak.

Read the rest of our Special Issue on On Chesil Beach here >>