Garrett Bradley discusses her new documentary, Time, a non-linear document of one woman’s emotional landscape over the 20 years of her husband’s incarceration.

Towards the end of Garrett Bradley’s New York Times Op-Doc, Alone, a woman imparts some blistering wisdom to the film’s subject, Aloné Watts, a young Black woman debating whether or not to marry her incarcerated boyfriend. The woman who speaks to Aloné is activist Fox Rich. “This system breaks you apart,” she tells Aloné. “It is designed just like slavery to tear you apart. And instead of using the whip, they use mother time.” Although Bradley never properly introduces the viewer to Fox in Alone, her insights and authority tell us that this is a woman with years, perhaps even decades, of first-hand experience with such a system.

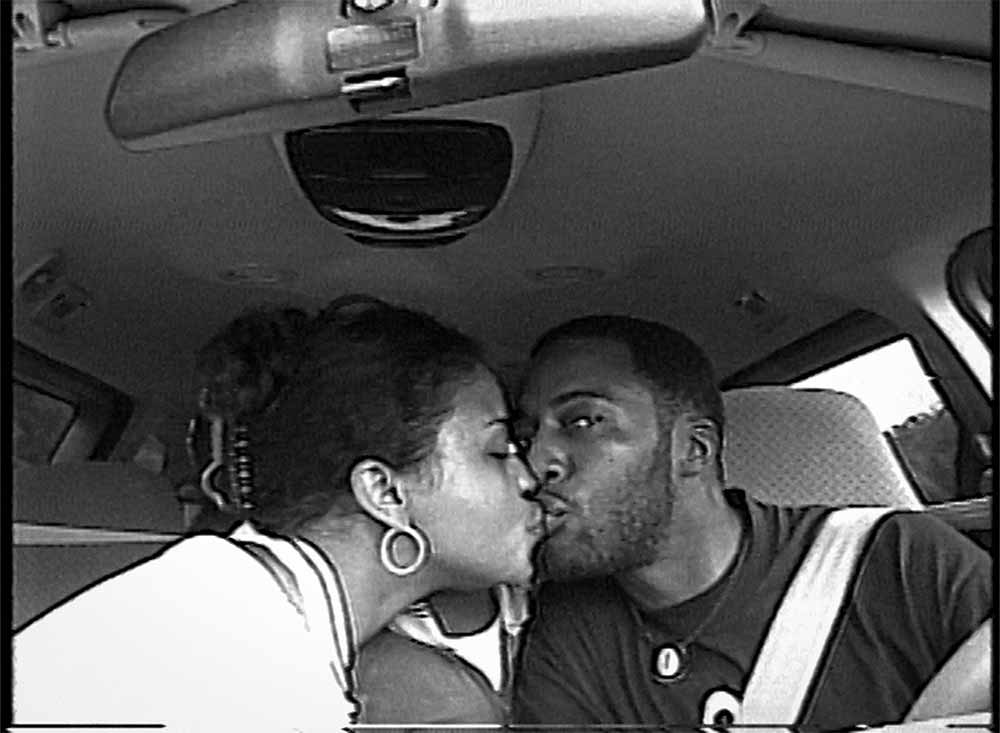

In Time, a feature-length project that Bradley calls “a sister film to Alone,” we take a close-up look at Fox. The film is half contemporary black-and-white footage that Bradley shot, and half Fox’s own black-and-white home videos that span two decades. The result is a non-linear document of one woman’s emotional landscape over 20 years. At the start of those 20 years, Fox’s husband, Robert, was sent to prison for robbing a bank under desperate financial circumstances; Fox herself did a few years of time for aiding the operation. The home videos document Fox’s journey as a young woman adjusting to life without Robert, raising their kids on her own, and committing herself to activism. In the present day, Fox is a respected activist and businesswoman, and her sons have grown into men with promising futures. But she’s still in limbo wondering if this will be the year whenRobert finally gets out.

I spoke to Garrett Bradley over Zoom about gaining intimate access to Fox’s daily life, structuring the film as a love story, and how she attempted to make visible the invisible problem of incarceration.

7R: I gather that you had shot all of the contemporary footage we see in the film before Fox Rich gave you her archive of home videos. Can you tell me about your original vision for this film and how those home videos changed that?

Garrett Bradley: So much of it was coming off of making Alone, which is a short 13-minute film, that I see as being Time’s sister film. I went into the process thinking that I wanted to make a sister film to Alone that is also looking at incarceration from a familiar and a Black, feminist, Southern perspective. A lot of the aesthetic choices were coming from that previous film.

When Fox gave me this incredible archive, it challenged a lot of those formal and aesthetic rules that I was creating, I think for the better. The film’s editor, Gabe Rhodes, talked through the material and thought a lot about the materiality and texture and colour spectrum of the archive relative to our newer footage.

Iit was about trying to find entry points that were emotional and drove the narrative forward, and trying to weave all those things together. There were a lot of ways in which the archive informed the overall direction we took. The film would be nothing without the archive to a certain extent. It revealed things that I myself would never have been able to capture in an interview or even in the present day.

7R: How did it challenge your conception of the material?

Garrett Bradley: I think that Fox’s youth and her free spirit was not something that people could feel and understand just in her telling me who she was. It was something we could really feel and see in the archive.

It [the archive] offers this really incredible opportunity to illustrate the full dimensionality of the family. Who we are as people is not just the moment that we meet each other. We are an accumulation of all the things we’ve experienced up until that moment.

7R: How did you think about the concept of time in the structure of the film? We jump back and forth in time, and you don’t overly signal where we are in time at any given moment.

Garrett Bradley: I think that the way in which we were able to achieve that was to really steadfastly focus on the mythological way of telling a love story, of really focusing on love and unity. That allowed us to be perpetually moving forward but also go backwards at the same time. If the film was coming from a direction that was squarely rooted in statistics or facts or the legal system or the bureaucracy, a lot of the details of the case itself, it would have been not only difficult [to structure], but also inaccurate. But love, even though it’s seemingly abstract, is something that truly, not to sound corny, stands the test of time and can be entered at any point throughout the film.

7R: How did you think about what the structure of a love story is and how to convey that?

Garrett Bradley: I think that the structure of it is that it never stopped! (laughs) It started, and then it never stopped, you know? Nothing was going to separate them. Part of the story is how they did that. How does one accomplish keeping your loved ones close to you over the course of 21 years? How do you keep your faith in love itself over the course of that time? We see Fox go through the ebb and flow of that emotion and the effects and consequences and sacrifices that it takes to maintain that goal over the course of that time. That is what is guiding the film, to a certain extent. That’s what creates scenes.

7R: Can you tell me a bit more about how you planned the shoot with Fox? The film is so stylistically meticulous and thought out.

Garrett Bradley: I shot list actually. I’m often right next to the cameraperson that I’m working with, zooming myself, or racking focus. It’s usually just the two of us. I’m intimately involved with where the camera’s going and how we want to see things. Not all camera people like to work that way, but I’ve been really fortunate.

With every documentary filmmaker, there’s that question of, you’re going to have to stop at a certain point, and you don’t know when you’re going to be at that point. For me, I just had to say to myself, every day, if this is the last day of shooting, what will I have thus far? What’s something that I can accomplish that’s not aspirational, that’s not hyper-focused on some perceived or predetermined ending of what the film should be?

If there’s one thing that people [take] away from this film, I want it to be that the system is so entangled in daily life that one cannot separate themselves from the bureaucracy and the pain of the prison industrial complex when you’re a part of it. So I focused a lot on her [Fox’s] daily life and the family’s daily life. The moments in their life that were important to them still showed us when the absence or the presence of the system had a daily effect.

7R: How do you shot list a documentary?

Garrett Bradley: I’m not just entering somebody’s life, and I don’t see them as subjects. I get to know people, and I let them get to know me. I want there to be a level of vulnerability and understanding with one another, so much so that I can ideally anticipate how they’re going to move through space.

How does Fox move through her office? Where does she like to sit? The Xerox machine is over there, and her chair is over there, and the computer is over there. I was really trying to understand her behaviour so I could anticipate things and make intentional formal choices. That’s different than not knowing, and therefore, having to be there for every single moment of a person’s life, and usually behind them, chasing after them.

7R: I loved the scene where we see Fox give an impassioned speech. You often cut to the faces of the people in the audience, intently listening and being moved by what she’s saying. Can you tell me about how you approached shooting that speech?

Garrett Bradley: We had two cameras. Actually, a huge source of inspiration for that was Zabriskie Point (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1970), a beautiful film. The opening of that is at USC, and it’s a conversation with white students and members of the Black Panther party who are discussing what white allyship is.

It’s a really important film for this current moment. So much of the way in which those moments are captured is about really revelling in the faces of the audience and really wanting to be with people. I wanted viewers to feel as if they are placed in that room with Fox and the audience.

[Shooting Fox with] Dutch low angles comes from looking at propaganda films, posters, and imagery and thinking about how we create heroes in our culture. I was working off a lot of the same aesthetic premises.

7R: How did you approach shooting the scenes of Fox waiting for phone calls about her husband’s legal case and being put on hold? The waiting feels so fraught and excruciating.

Garrett Bradley: While we were shooting, there wasn’t much to do. I think it goes back to this thing of being able to anticipate behaviour and being really confident about where you’re putting your camera. I didn’t feel like we needed to do anything. I felt so intimately connected with Fox, and I felt the camera was not looking at her; we were with her.

It was kind of the same thing with the edit. There wasn’t a whole lot of overthinking that needed to happen. It [had to be] a real-time experience. I wanted viewers to be with Fox and experience time in its most literal sense with her in those moments. Time is not literal throughout the rest of the film.

7R: I really loved how you chose to introduce Fox to the audience in the present day, with a scene of her talking with a cameraman who’s shooting her for a commercial, but she’s directing him. We meet her as a woman with agency over her own image. Why did you choose this as an introduction?

Garrett Bradley: I thought it was really important for exactly those reasons. I wanted people to meet her on her terms right away.

When we were editing, there were a lot of questions around, “But Garrett, where are you as a filmmaker? Are you letting her take over the framing and understanding?” From some viewers in early stages of the cut, there was distrust of what the truth was and who was in control, which I thought was really fascinating.

I think it reveals when we become comfortable, as viewers, about who’s in control and who isn’t. When we have a strong Black woman who’s in control and is of herself and of her surroundings, all of a sudden, we take issue with it or become uncomfortable with this idea of objectivity or neutrality. I clearly was there, as a filmmaker, because I’m choosing what to show, what not to show, and how to show it. Which is the other 50% of it.

7R: Fox’s husband, Robert, is rarely seen in the film. How did you make sure we felt his absence?

Garrett Bradley: That that was a huge part of the conversation: how to speak to and illustrate issues around erasure and invisibility without reinforcing the same problems. We had to point to it through empty chairs or the emotion articulated through the family itself. But we also made sure that, at the end of the film, there was a moment when we hear from Robert. We see him, and he has an opinion and something to say. That was so crucial.

Part of the incredible and unfortunate challenge, and one of the failures I feel, honestly, as a filmmaker, is that incarceration is this seemingly invisible issue. It’s very difficult to get into prisons and to see what’s going on there. The access is extremely limited. There’s 2.3 million people who are incarcerated in the country, and the fact that people aren’t completely outraged by the state of it, as a system, is because they can’t see it.

When we think about war nowadays and what was happening in Vietnam, people were protesting and were outraged by the war in Vietnam because, for the first time, they could see it on their TVs. And then quickly thereafter, they were met with greenscreens and a neutrality and absence of what was happening. People tap out.

Angola, which was where Robert was incarcerated for 21 years, was made up of several different plantations. It was named after the people who were enslaved and brought over from Angola. It was consolidated into a single plantation, and then it was turned into a penitentiary. It’s 18,000 acres of land, which even our drone could not capture the magnitude of. There are so many ways we can think about where we are in this moment. So much of it has to do with image-making and the lack of it, as well.

7R: How did you approach crafting the film’s ending? There’s a delicate balance there between portraying the joy of a family reunited but also ensuring that you keep the injustice of an ongoing fight and everything they lost in two decades in focus.

Garrett Bradley: I felt like there could be a whole other film about what happens next, about Robert’s re-entry process and about the family’s next journey. It was important for me to end the film where it did as Fox and the family had accomplished what they sought out to do.

The last few scenes of the film are a last attempt at getting [viewers] to question the worthiness of that sentence, the worthiness of time spent and given. What did it really accomplish? My hope is that, at a minimum, you understand the privilege of one’s own access to intimacy.

7R: How did you think about the sound design in the film?

Garrett Bradley: I work with Zack Howard, who has mixed and designed a lot of my films. I love sound. I love playing with it. I try to start working with it as early as possible in the editing process because I think we respond to sound as much as we do to images.

We thought about certain themes we wanted to exist throughout the work, including cars, highways, and movement. We inserted those throughout the sonic landscape even when they weren’t necessary in a literal sense.