Films about police brutality in the UK are sorely lacking, but this year’s London Film Festival gave us two: Ken Fero’s mishandled Ultraviolence and Steve McQueen’s brilliant Mangrove. Read more coverage of the London Film Festival.

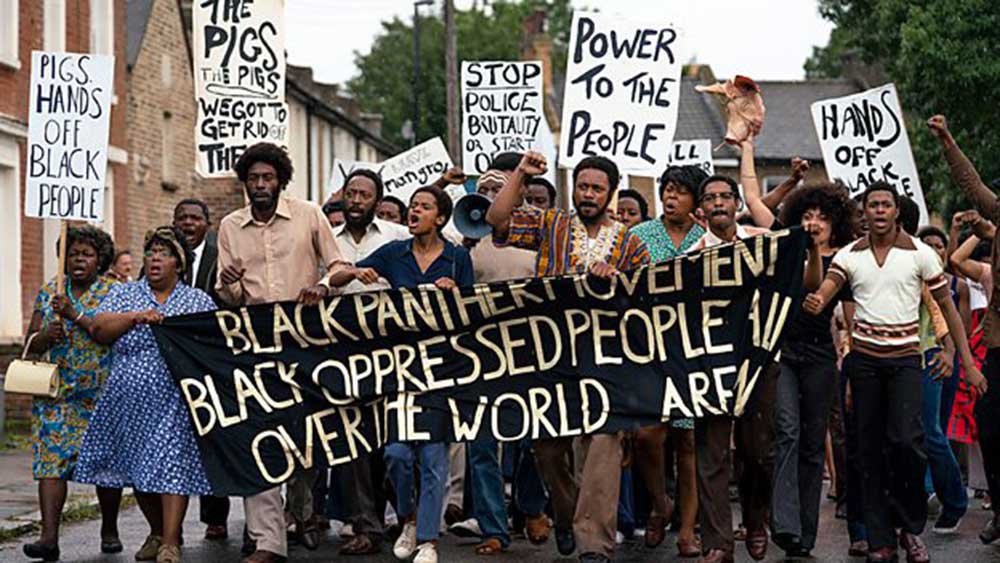

Films about police brutality in the UK are sorely lacking, which contributes to the harmful idea that it’s not a problem on our island. While plenty of US cinema has tackled the topic — Blindspotting, The Hate U Give, Monsters and Men, and Fruitvale Station to name a few — police brutality is still largely ignored by British cinema. At this year’s London Film Festival, however, there were two: Steve McQueen’s rousing Mangrove and Ken Fero’s mishandled documentary Ultraviolence. Mangrove, the first chapter in McQueen’s five-part film series, Small Axe, tells the story of The Mangrove Nine who were arrested after protesting outside a police station in 1968 and fought for justice in the High Court the next year. Ultraviolence methodically chronicles the deaths in police custody of several Black men and one Brazilian man. While Mangrove is a detailed look at the systemic racism on every level of the British justice system, the latter verges on misery porn.

Through verité footage, found footage, animation, and interviews with family members, Ultraviolence conveys the horror faced by the men who died in police custody, and the tragedy their families suffered in the aftermath. But was Fero the right person to tell this story? His long-term commitment to bringing issues of police brutality to light is admirable; 18 years ago, in 2002, he made another documentary on the subject called Injustice. But throughout Ultraviolence, you can feel his gaze as a white person who sympathises for, but isn’t directly affected by, racialized violence. (It’s worth noting that Fero’s co-writer, Tariq Mehmood, isn’t white.)

For one, Fero crassly frames the film around himself and his own experiences. The majority of the film’s narration is voiced by him, which centres his interpretation of the horrifying images we’re seeing rather than the images themselves or the interpretations of people of colour. He constantly shows us a scene, and then includes narration that reiterates exactly what we’ve just seen, as if it doesn’t matter until Fero has personally explained to us why it matters. Most egregiously, the framing device of the film is that this narration is a ‘letter’ Fero is writing to his son to warn him that there is violence in the world that he should fight against. One of the first images in the film is a family photo of Fero’s children, which comes before a photo of a Black family that was directly affected by police brutality. This implicitly frames all the violence against people of colour that we witness in the film as a learning opportunity, particularly for white people.

There is a fine line between depicting violence as a wake-up call versus misery porn, and Fero crosses over to the latter by providing little context for the brutality. He seems more concerned with making himself seem smart: at one point, over a traumatising minutes-long snippet of CCTV footage of a Black man dying, he briefly interrupts the audio to quote Pasolini’s theory about the cinematic long take.Fero also frequently blasts big, lurid, brightly-coloured block letters on the screen that shout words and phrases like “LIAR” and “WE ARE BEING CONTAINED,” as if these messages weren’t already obvious. The film is so preoccupied with showing us the spectacle of tragedy and violence that there’s no time to explore how systemic racism brews and functions. There’s so little screen space dedicated to how we might dismantle it, beyond campaigning for the cops involved with specific murders to be locked up.

Where Ultraviolence is all about the violence, as its title indicates, Mangrove demonstrates both the physical brutality and the brutality of the justice system, before going on to illustrate what it actually means to fight against it. McQueen places the subtler systemic racism faced by The Mangrove Nine in the High Court on the same level as the racist physical abuse of the police. He dedicates the whole second half of the film, which is set almost entirely in a courtroom, to exploring this.

McQueen’s film pulls no punches when it comes to exhibiting the callous brutality of London’s police force, but he focuses on how their violence disrupts peace and community over how it damages the human body. The first half of the film establishes the Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill as a hub for the West Indies community: it’s a place for them to eat food that reminds them of home and chat with friendly faces; McQueen shoots the interior in warm yellows while outside is a harsh blue. It’s a shock, then, when this safe haven gets interrupted by a raid of police, who burst in through the doors without a word of warning and immediately start smashing the walls and furniture with their batons.

McQueen examines how the power and prejudices of the police are learned and enforced through a sequence where he briefly invites us into the police station. At the station, a new recruit is inducted into the force’s racist attitudes as if it’s some kind of game: they play cards, and the loser has to arrest the first Black man they see on the street. The scene that follows is chilling not just for the violence it implies but for how McQueen uses the camera to demonstrate the policemen’s power. We watch the incident from the cold remove of the police van’s front window — the glass blocking out any sounds of panic just as the police ignore the humanity of their victim. While the victim runs for his life, the driver of the van barely needs to speed up in order to catch up to him; the power of a vehicle over a man on foot becomes a metaphor for the police’s power over the marginalised.

In Mangrove, racialized violence doesn’t stop with police brutality; it’s baked into the UK justice system. McQueen’s film spends half of its runtime on the police violence and the other half on the systemic racism of the courtroom where it seems impossible for The Mangrove Nine to be exonerated. First, some of The Nine’s family members are barred at the door from watching the proceedings, even though they have a ticket to get in. Then the Nine’s request for an all-Black jury is denied, so they’re immediately set back by having to argue a case that involves racism to a majority-white jury. Throughout the trial, the judge displays a short temper with the Black defendants and gives leeway to the white prosecution, even as he claims impartiality. At one point, a guard even attacks two of the Nine unprovoked and locks them in a cell during a court break. The Nine are tasked with not just presenting a compelling case but circumventing the racist biases of the court while they do it.

So perhaps we don’t need Ultraviolence when we have Mangrove. Or perhaps the ignorance around police brutality in the UK is so dire that we need both. It’s worth noting that the acclaimed final film in McQueen’s Small Axe series, Red, White and Blue, which I haven’t seen yet, deals with the police even more directly. John Boyega plays a young Black Londoner who witnesses the racism of the police force and decides to join up so he can change it from within. The differences between Ultraviolence and Mangrove are evidence enough that the UK needs Black filmmakers, not well-meaning white filmmakers, making films that address the nuance of racist violence. As McQueen wrote in a June op-ed for The Observer: “I made three films in the States, and it seems like nothing has really changed in the interim in Britain. The UK is so far behind in terms of representation, it’s shameful.”

READ: More coverage of the London Film Festival >>