Francis Lee discusses excavating the life of paleontologist Mary Anning in Ammonite, and how he used sound design to immerse us in her world.

Read (and listen to) more about Francis Lee’s Ammonite here. Check out our ebook about Lee’s God’s Own Country here.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

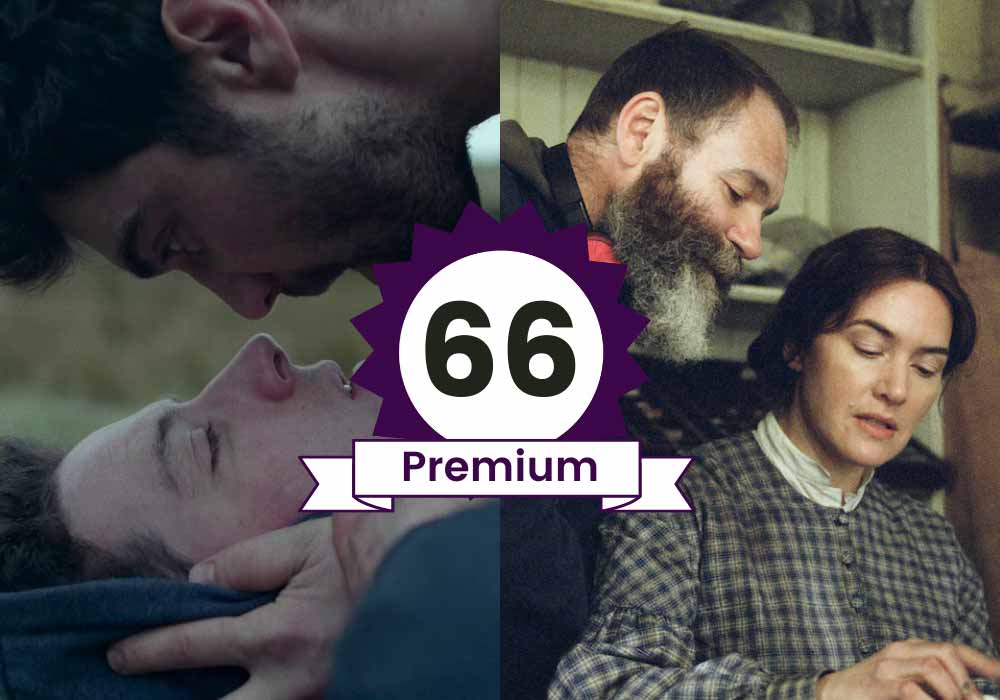

Francis Lee’s second feature, Ammonite, is an apt companion piece with his debut, God’s Own Country. Ammonite is a fictionalised account of real life 19th-century paleontologist Mary Anning (Kate Winslet), a working class woman who lived on the cold, windy coast of Lyme Regis, Dorset and worked with her hands, in the mud, excavating fossils. As with Johnny (Josh O’Connor) in God’s Own Country, Mary is a withdrawn, lonely soul; and just like Johnny, the love of a more extroverted outsider pushes Mary out of her shell.

These similarities only serve to underscore how much of a step up Ammonite is from God’s Own Country: it’s an expansion in scale, scope, and ideas. The outsider in Ammonite is Charlotte Murchison (Saoirse Ronan), an upper class woman from London whose husband has left her in Lyme Regis to “take the sea air” in order to recover from “melancholia” after losing a child. Unlike the eventually serendipitous relationship between Johnny and Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu) in God’s Own Country, the dynamic between Mary and Charlotte is more complicated because it’s fraught with class tension. Charlotte’s time in Lyme, as a visitor in Mary’s small and bare home, is a bubble in which the barriers of class are less pronounced. When Charlotte returns to her home of elaborate dresses, fancy homes, and servants in London, the context of their relationship changes completely.

While God’s Own Country was a lovely but straightforward love story, Ammonite is an altogether more ambitious effort. Lee has one eye on the romance and one eye on the lost history it represents — of historically ignored lesbian relationships, and of Mary Anning herself, who was a pioneer in her field but was never appreciated in her time. “There’s hardly anything written about Mary Anning when she was alive,” Lee told me, which meant he had to fill in the blanks of history by inventing parts of Mary’s story, including her relationship with Charlotte.

I spoke with Francis Lee over Zoom about what attracted him to Mary Anning, filling in what history books left out, and how sound design was absolutely crucial to creating Mary’s world.

Seventh Row (7R): What made you feel like a romance was the best avenue through which to explore Mary Anning’s life?

Francis Lee: I was so instantly struck with Mary, not just her accomplishments but her circumstances. Here was this woman born into a life of poverty, working class, in this totally patriarchal, class-ridden society. Through her own ingenuity and courage and damn hard work, she rose to being who we would now call one of the leading paleontologists of her generation. There was just something about that which really struck me personally and paralleled with my own life.

I knew I didn’t want to write a biopic. I wanted to imagine a Mary, my Mary, if you like. I also wanted to try, as much as possible, to respect her and elevate her to a place that maybe she hadn’t been in her lifetime, and give her possibilities that she may or may not have had.

I’m obsessed with intimate human relationships, how we operate in them, and how we manage them, so I knew I wanted her to have a romance. But in this patriarchal society where men owned women, and where Mary therefore would be a subject to a man, particularly given how men had reappropriated her work and overlooked her, I felt it was much more respectful and elevating to give her a relationship with a woman. It felt so much more equal.

At the same time, I was reading a lot about same-sex relationships in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and this paper came across my desk written by Caroll-Smith Rosenberg that investigated female and female relationships in the period, which are very well documented through letters. They describe these wonderful, caring, lifelong, supportive, and passionate relationships between women. I wanted to give a voice to that.

7R: What made you want to set Ammonite at this point in Mary’s life, in her mid-40s? If we assume Mary in the film is the same age as Kate Winslet is in real life, Mary would have died just a few years after the film is set.

Francis Lee: That’s correct!

For me, it was about coming to someone’s life after they’ve worked super hard, after they’ve had success. Fossils were very fashionable at one point in Mary’s life, and she did make good money, and life was OK. Then fossils fell out of fashion, and Mary became poor again and was back to doing menial work. I wanted to look at that part of her life where she was just getting through it, trying to survive.

I wanted to look at how bringing in somebody else for her to have a relationship with at this point in her life might be about growth for Mary, might be about reigniting that passion for her work or for a relationship.

Also, it’s an age where I feel, particularly for women, we don’t see that many dynamic stories on screen.

7R: God’s Own Country and Ammonite have a lot of character and structural similarities: they follow closed off characters who work with the hands, who open up due to a romantic relationship. Although the endings of those romantic relationships are quite different. Did you see them as companion pieces?

Francis Lee: I was interested in continuing my work around relationships and about loneliness and loss. I was also interested in continuing my work around landscape and how that forms people, both physically and emotionally, and how work dominates some people and their lives. I don’t know how conscious it was, but those are the things I obsess about.

For me, Ammonite just felt like quite a different emotional space in terms of where the main character is and what they’re going through, and that’s why the ending is somewhat different. There was an ending, when I first wrote it, that was really sewn up and happy, but it didn’t feel like it actually fitted the journey of where Mary’s at and what she’s saying about who she is and what she wants. I think you’re right. They probably are very good companion pieces.

7R: I noticed this focus on labourers in the film, that I really loved: the opening sounds and images are of a maid washing the floor of a museum; later, we see the men pushing Charlotte’s bathing cart out to sea before we see Charlotte herself; and you also give us character beats with the maids who serve Charlotte both in Dorset and in London. How did you craft that opening and think about threading that theme through the film?

Francis Lee: The person playing the museum cleaner is my best friend! (laughs)

I wanted the opening of the film to almost tell you everything the film was going to be about. Even now, when we go into spaces like museums or art galleries, we look at the things in the cabinets, and we look at the things on the wall, all the things that are elevated, that we’re told are special. We don’t look at the infrastructure around it. But when you do, you see those people. You see the people cleaning the floors, the people living in those spaces who are just as much a part of those spaces as those elevated art works or relics. Those people go unseen, and they don’t have voices, and we don’t focus on them.

Everything about this film and Mary Anning, for me, felt like these people didn’t have voices. They aren’t recorded. There’s hardly anything written about Mary Anning when she was alive. All of these people, like the museum cleaning lady, I wanted to give a voice to, but also respect in terms of how hard that life was, and how they’re defined by their work. She’s a cleaning lady. The men who carry in the fossil [in the opening scene and command the maid to move out of their way] feel they’re more important and she’s nothing. I did try to thread that throughout the film, seeing people, even if they’re not the main characters.

My favourite one is when Mary Anning is walking down the street where Charlotte lives, just before she gets to Charlotte’s house: she looks at a cleaning woman who’s cleaning the front step of another house. I really loved that. The house where she’s cleaning the front step of is the house where they shot Phantom Thread. It’s like my favourite film, so I wanted to do a little homage and clean the step of the Phantom Thread house. But again, it was seeing what women were doing, how their toil was everywhere, and they didn’t really have a voice.

7R: The sound design is so crucial to the atmosphere and intimacy in this film. I know you’re a big fan of sound design. How did you think about the sound design in Ammonite?

Francis Lee: First of all, I was very lucky to work with a beautiful man and wonderful sound designer called Johnnie Burn, who was super excited to come and work in the way in which I like to work. Sound is something I do really obsess about and prioritise. Although we record all the natural sound while we’re filming, when we go into the edit, we start the sound work very, very early. We don’t leave it until the end, which is often what happens. We start straight away with the picture, and we strip all the sound we’ve recorded off the film apart from the dialogue, and then we start rebuilding it with sounds that Johnnie and his team have gone off to all the locations and recorded. We have this massive library of hundreds of sounds of the sea, hundreds of winds, hundreds of different types of birds, all of these sounds that we then start to play with.

What we try to do is underpin every single scene emotionally and physically with the sound. For example, in this film, the sea is always present. Unless we purposefully have taken it out for a reason, the sea is always there. I’m not a great fan of the seaside and being near the sea, and it took me ages to work out why, but it’s because of the constant lapping of the waves up and out, that tide, that rhythm. To me, it feels like it’s just your life passing you by, and whatever you do, that sea will continue. It makes me feel pretty immaterial in an existentialist way. We were layering that in.

The winds are orchestrated to happen at various points, the ups in the wind, the downs in the wind, the whistling wind, and the birdsong. We had to take out every single natural bird sound, and then replace them, at various stages, with very specific birds and songs that were underpinning that scene. When Mary goes to Elizabeth Philpot’s house and knocks on the door, there’s a robin, and the song that the robin is singing is a warning sign. Seagulls are very important, where they happen, and the different sounds they’re making. Seagulls, to me, have always been about freedom: the fact that they can fly so far away and out to sea. But there’s also a loneliness about them, and they’re very linked to Charlotte. They’re always there when Charlotte is struggling.

It is my ambition one day to just make a film of sound, with no picture. I don’t know if that would go down well in cinemas. Maybe in a gallery. (laughs)

7R: In which scenes did you take out the ocean, and why was that?

Francis Lee: We took it out when Mary said goodbye to Charlotte. She comes back to the house, goes upstairs into her room, and closes the door. I’m pretty sure we took all the sound out of that, except for her footsteps. When Molly’s [Mary’s mother is] dead and Mary is dressing her in her room, we kept the sea going there because it makes you feel like you’re immaterial. And then, just before Mary leaves the room, we took all the sound out.

7R: God’s Own Country was shot in the Yorkshire landscape that you’re deeply familiar with, so you had an instinctive idea of how to shoot it, whereas with Ammonite, I’m assuming the Dorset coast is a landscape you’re far less familiar with. How did you navigate that?

Francis Lee: I went and stayed there for quite a while and tried to absorb it, tried to be out in all weathers, tried to see its ferocity, as well as its beauty, and to see its struggle. Those cliffs are very dangerous, and they change all the time, because the tide comes right up and erodes them. So I was trying to spend time there.

Also, in that little town of Lyme Regis, all the houses are built on top of each other. Everybody looks in on each other. It’s a very small community. I tried to really embed what that must have felt like.

7R: How did you work with your DP Stéphane Fontaine to figure out how to shoot that landscape?

Francis Lee: I was very blessed with Stéphane Fontaine, who’s just wonderful. We worked for maybe three or four months before shooting the film, just sharing references and talking about the film. We talked a lot about textures, actually, and how that translated to the visual, and how that should feel. I wanted it to feel a very tactile film.

We very quickly discovered that we wanted it to feel very up close and personal, that we wanted the camera to feel fluid and reflect the movement and emotions of the characters. We were shooting in very small, internal spaces. It was very much about trying to reflect the size of those spaces.

With the landscape, similar to God’s Own Country, we had a conversation where I said, “I don’t necessarily always need to see the landscape, but I do need to see the effect the landscape has on the characters.” So lots of closeups of mud and dirty hands and that kind of hardscrabble life that Mary was living.

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch great films like Ammonite at virtual cinemas and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.

Click here to subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter.

More on Francis Lee’s debut, God’s Own Country…

Take home our ebook on Francis Lee’s God’s Own Country

Return to the Yorkshire moors and discover how Lee, Secareanu, and O’Connor brought Johnny’s and Gheorghe’s romance to life.