From Petite Maman to I’m Your Man to The Worst Person in the World, Seventh Row’s editors pick the thirty best films of 2021.

Read all of our best of 2021 coverage.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

On today’s Seventh Row Podcast episode on the best films of 2021, we concluded that it’s been an exceptional year for cinema, so much so that even our top ten couldn’t hold all the films we thought were enduringly special. What’s also striking is that, to find the incredible films that populate our top thirty of the year, we had to look outside of the USA, even though that’s the country that usually dominates awards and trade publications’ lists. Our list only features three American films, all of them documentaries, compared to last year’s ten.

We hope this list is a good example of the kind of curation we offer at Seventh Row, and an argument for why following our work is a good way to stay on top of the exceptional international and independent films that aren’t being talked about in mainstream circles. If you’ve not heard of some of these films, it’s not because they aren’t great, or perhaps even vital. To us, the cream of the crop of these films are ones that look at societal systems, structures,, and psychology with a clear eye, and allow you, the viewer, to perceive the world around you with a keener eye.

We let subscribers to our newsletter know about great under-the-radar films and where they’re streaming every single week on our newsletter. Subscribe for free now if you don’t want to miss any of the films that will show up on our best of 2022 list.

30. Drive My Car (Ryûsuke Hamaguchi)

Drive My Car is the second film Ryûsuke Hamaguchi released this year, and while we narrowly prefer Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, the less sombre of the two, both are of exceptional quality. They’re also both films that contemplate the unknowability of other people, portraying relationships in which characters use each other to process their emotions about completely different people and events in their lives. Drive My Car also has a play-within-a-film concept: it follows theatre director and actor Yûsuke (Hidetoshi Nishijima) as he stages a production of Uncle Vanya. It’s slow, contemplative, and three-hours long, but completely absorbing and worth the time it takes to process. Orla Smith

29. Boy Meets Boy (Daniel Sánchez López)

From our review: “There’s been no shortage of cheap, mumblecore knock-offs of films like Weekend and Before Sunrise — filmmakers seem to think they can just shoot two people chatting in a vaguely naturalistic style and become the next Linklater. Boy Meets Boy is made of stronger stuff. It stands out from the crowd for the genuine chemistry between its leads, as well as the specificity of both its characters and the questions they’re asking themselves. Harry (Matthew James Morrison) and Johannes (Alexandros Koutsoulis) may be in suspiciously similar circumstances to Rusell and Glen in Weekend, but they’re also younger, and of a younger generation. They’re grappling with career uncertainty, Grindr hookup culture, and the reality of being a young gay man in a culture and place that’s more accepting of queerness than ever. Unlike Russell and Glen, they don’t have to worry about being physically affectionate in public, but they’re still grappling with societal expectations and internalised homophobia that runs deep.” Read the full review.

28. Bootlegger (Caroline Monnet)

Caroline Monnet’s feature debut, Bootlegger, follows a young Indigenous lawyer, Mani (Devery Jacobs), who returns to her home reserve, after years living away, in order to complete her graduate school research. On the reserve, alcohol has been banned — not by the Canadian government, as was the case in years past, but by the Indigenous leaders themselves. Mani is trying to encourage the creation of a referendum to let the community decide whether to keep the ban on alcohol which echoes colonialist history.

Bootlegger is thoughtful in its exploration of what it means to become detached from your home as an Indigenous woman, as well as how Indigenous people can end up becoming complicit in their own colonisation because so few options are available to them. The film also positions alcohol as just one way in which the community is being destroyed (e.g., forestry is another). Jacobs is fantastic, as always, here speaking multiple languages. The film is also gorgeously shot. Not all of Monnet’s ideas are fully explored, but it’s certainly a conversation starter and essential viewing for Canadians. Alex Heeney

Read Alex’s profile of Bootlegger and Reservation Dogs star Devery Jacobs.

27. Moffie (Oliver Hermanus)

From the introduction to our interview with Oliver Hermanus: “South Africa, 1981: at seventeen, all white boys are conscripted into the army for two years, forced to fight in the Border War, a white supremecist campaign from a white supremecist institution. Perhaps even more important to the government than getting foot soldiers for the battles is the indoctrination of an entire generation to uphold apartheid. Here, young men learn that their goal is to dominate, to hold power over others. It starts with white supremacy, but as Oliver Hermanus’s Moffie dissects, it’s a short hop and a skip to other forms of oppression, like homophobia.

Nicholas (Kai Luke Brummer) is our entry point into this world, and we meet him on the last night before he’s about to be shipped off to do his military service. His mother and her paramour act as though it’s a rite of passage, but the quiet, introspective — and as we soon learn, gay — Nicholas isn’t quite so excited. The initiation process starts on the train to the training facility, where the boys preemptively get drunk, and take out their aggression on any target they can. One such target is an elderly Black man (Israel Ngqawuza) in a suit on a bench, sitting on the platform at a station they pass, who doesn’t stand up in deference to the train’s white passengers. It’s a harrowing scene in which groupthink kicks in and the boys shout insults and lob a bag of vomit at the man. It’s also a succinct illustration of how much the white population relies on oppressing others.” Read the full interview.

26. Procession (Robert Greene)

From the introduction to our interview with Robert Greene: “‘I don’t use the word healing,’ Greene clarified when I spoke to him about Procession. ‘Healing is possible, certainly, but especially with the guys that we worked with in Procession, they’re not looking for healing. They’re looking for meaning, and they’re looking for help.’ In the film, Greene works collaboratively with six survivors of childhood sexual assault, and enlists a drama therapist, Monica Phinney, to help ensure the process is helpful, rather than retraumatising. Phinney describes her work as ‘the intentional use of roleplay to achieve a therapeutic goal.’ To that end, each man writes a short script centred around a real or imagined scene from their childhood, and sets about committing it to film. Sometimes, that even means returning to the precise location of their trauma. It’s an emotional experience, but one that helps them take steps to processing the pain in their pasts.

Greene describes Procession, as ‘the culmination of [his] work;’ I have to agree with his sentiment. Certainly, watching all of his films chronologically, leading up to Procession, was a striking experience. Collectively, they paint a portrait of Greene’s progression as an artist and as a person over the past decade, as he’s grown to realise the power of filmmaking as a therapeutic process, and thus gained a clearer understanding of why he wants to make films in the first place.” Read the full interview.

25. North by Current (Angelo Madsen Minax)

From the introduction to our interview with Angelo Madsen Minax: “For filmmaker Angelo Madsen Minax, returning home to rural Michigan meant confronting his demons and helping to rebuild a fractured family unit. For years, he kept his distance from home, moving to the big city where he could embrace and explore his transgender identity away from his Mormon upbringing. About ten years ago, the death of his young niece, Kalla, changed everything. Minax returned home to support his grieving sister and parents. He was also there to fight against his brother-in-law’s prison sentence: his brother-in-law was accused of killing Kalla, a sentence which was later revoked when it was exposed that the police had covered up evidence. From this trying time, the project of making North by Current was born.

North by Current is a lyrical documentary, shot periodically between 2015 and 2021, capturing Minax and his family’s journey through grieving. Minax describes it as an ‘essay film’: it’s heavy on subjective voiceover, some of which is voiced by Minax himself, and some by an unidentified child narrator. It’s never explained who this child is: Are they an imagined version of Kalla? Minax or his sister as children? Or some other, omniscient being, here to provide a spiritual commentary on the situation? This ambiguous voiceover is part and parcel with the film’s singular perspective, more concerned with capturing a state of mind or a feeling than telling us everything about Minax and his family.” Read the full interview.

24. Quebexit (Joshua Demers)

From the introduction to our interview with Joshua Demers: “Canadian satire on film is still very much in its infancy, with Philippe Falardeau’s brilliant 2015 film, My Internship in Canada, essentially hailing its birth. With Joshua Demers’s Québexit, there’s now another entry in this nascent genre, and it’s an exciting, and very funny, one. Both My Internship and Québexit share an interest in the culture clash between anglophones, Québécois Francophones, and Indigenous people.

But Demers’s film takes the important next step of actually involving all three groups in the screenwriting process: he co-wrote the film with bilingual Québécois francophone actor Xavier Yuvens and Cree actress-director-writer Gail Maurice (recently seen on CBC’s Trickster as Georgina). The collaborative process really pays off because you feel like you’re getting an insider perspective on each of the characters, which ensures all of them are three-dimensional and the humour feels very, very specific. It also allows the film to be trilingual — in English, French, and Cree — which adds another level of authenticity and nuance.” Read the full interview.

23. Sweat (Magnus von Horn)

From our review: “Few films have portrayed social media influencer culture as accurately and empathetically as Sweat. The easiest trap to fall into is characterising an influencer as shallow just because the content that they post is shallow; Magnus von Horn avoids this at every turn. Played beautifully by Magdalena Kolesnik, Sylwia feels three-dimensional, a woman who’s in over her head and desperate for intimacy amidst the alienation of online fame. She’s well meaning, and she’s also a very capable business owner — because as Sweat makes clear, being an influencer means being the head of your own mini-business. But just like so many of us, her lifestyle has become reliant on social media to a damaging extent.” Read the full review.

Read Orla’s interview with writer-director Magnus von Horn.

Listen to our podcast episode on Magnus von Horn’s The Here After and Sweat.

22. Wife of a Spy (Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

I’ll be shocked if Wife of a Spy doesn’t top our list for the best costume design of 2021: everything is absolutely gorgeous, well-tailored, and character-specific. It’s both of the time (the 1940s) and yet wouldn’t be out of place in the present. So come for the costumes, and stay for the really thoughtful character drama.

Satoko (Japan Society’s 2021 Honoree Yû Aoi) begins to suspect that her husband might be a foreign spy, so starts spying on him, in turn, trying to figure it out. What unfolds is a cat-and-mouse game between husband and wife, as well as the couple and the country, full of double-crossing and deceiving appearances. The fact that appearances aren’t quite what they seem is part of why the pristine costume design is so crucial. AH

21. The Courier (Dominic Cooke)

From the introduction to our interview with Dominic Cooke: “Set in the early 1960s, The Courier is based on the true story of British businessman Greville Wynne (Benedict Cumberbatch) who suddenly found himself working as a Cold War spy helping to put an end to the Cuban Missile Crisis. When Oleg Penkovsky (Merab Ninidze) made contact with the CIA about becoming a Russian source, they needed an amateur like Greville to do the leg work of getting his information, so as not to arouse suspicion. The film follows them through the thrill of the initial intelligence exchange, the deepening friendship that forms, and the aftermath of discovery. Just as Dominic Cooke’s On Chesil Beach explored the constrictive sexual mores of the time, The Courier is also about the restrictive societies that define both Greville’s and Oleg’s existence.” Read the full interview.

20. Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn (Radu Jude)

The winner of the Golden Bear at this year’s festival was Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, a left field choice because of just how bizarre it is, but predictable in the sense that it’s very much a “film of the moment”. Still, it’s certainly a statement for the jury to award top honours to a film that begins with an extended unsimilated sex scenes. The scene in question is an extremely OTT, comical homemade porn video made by the film’s main character, school teacher Emi (Katia Pascariu). When it accidentally leaks onto the internet, the parents at her school call a parent-teacher meeting to subject Emi to their moral-panicky rage and attempt to get her fired.

It was filmed during COVID and incorporates COVID into the world of the film. Poor mask wearing becomes an indicator of moral failure, such as when an indignant parent claims she’s “trying to do what’s best for the children” while wearing her mask under her nose. It feels cathartic to watch Jude relentlessly mock anti-maskers. It’s also incredibly anxiety-inducing, as the film reflects how little people care about actually protecting others, preferring to focus their outrage on an innocent woman’s sex life.

In the hilarious middle section of the film, Jude presents a series of visual jokes and puns, many of which relate to shameful parts of Romanian history. This vital piece of the film’s puzzle serves to place selfish, unsafe responses to COVID as just the latest in a long line of corrupt behaviour in Romania (although this behaviour is certainly recognisable in other parts of the world, too). Of course, it’s not long before the parents’ facade of polite concern is “unmasked” to reveal virulent anti-semitic and sexist tirades. OS

Look out for our profile of Radu Jude next week.

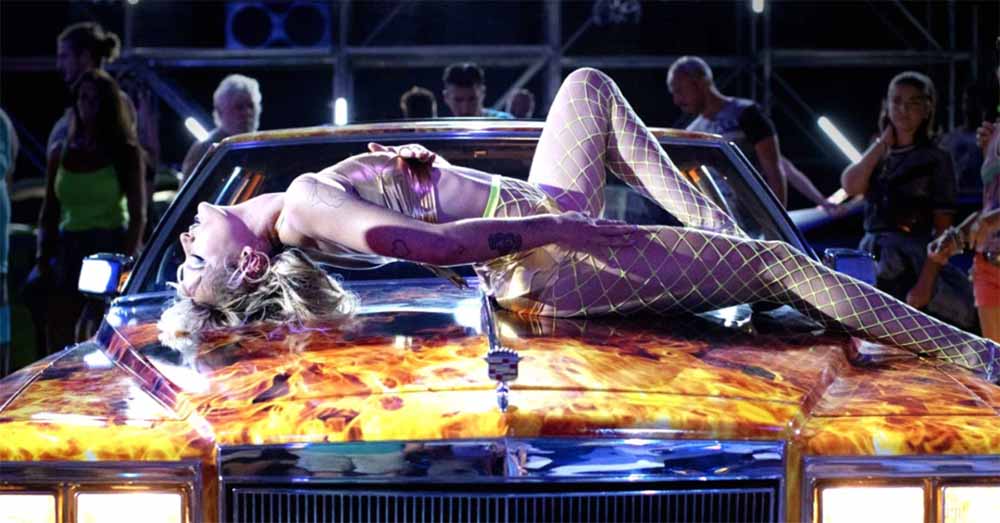

19. Titane (Julia Ducournau)

Raw director Julia Ducournau returns with Titane, a film that caused a sensation at Cannes, where it won the Palme d’Or. As always with any film featuring extreme, shocking content, the reactions have been divided and hyperbolic. It’s best to go into Titane with no expectations, and hopefully you’ll be won over by its thoughtful use of body horror to explore gender and identity.

The film follows Alexia (Agathe Rousselle), an erotic dancer who performs atop car bonnets while a crowd of mostly men leers on. She’s also a serial killer by night. What follows is a story about family, love, and the way the functions of your body can betray the way you want the world to see you. It’s often grotesque, but also sometimes sweet and heartfelt. It’ll certainly have you thinking and debating with friends afterwards, whether you love it or not. OS

Listen to our podcast on Julia Ducournau’s Titane.

18. Slalom (Charlène Favier)

From our review: “Charlène Favier’s Cannes-labelled directorial debut, Slalom, is a tense pas-de-deux between a 15-year-old professional skiing star, Lyz (Noée Abita), and her coach, Fred (Jérémie Renier). Like Una, the film is a complex exploration of the dynamics of an abusive relationship between a man in power and a child in his charge. Though it deals with sexual abuse, the film is most interested in Lyz’s perspective, avoiding judgement or sensationalism, while making Fred human if reprehensible.” Read the full review.

Read Alex’s interview with writer-director Charlène Favier.

Listen to our podcast on portrayals of childhood sexual assault in Slalom and Una.

17. Film about a Father Who (Lynne Sachs)

From the introduction to our profile of Lynne Sachs: “In the 1980s, documentary filmmaker Lynne Sachs started filming her father, Ira Sachs, a gregarious, womanising businessman. Now, three decades later, she’s finally finished making Film About a Father Who, a sprawling chronicle of her father’s life, and the children, wives, and girlfriends he left in his wake. That includes Lynne, her sister Dana, and her brother Ira Jr. (also a filmmaker). It also includes the six other children that their father had with various different women.

Film About a Father Who feels like a culmination of a career of family-focused work; it’s ambitious, attempting to take in the whole scope of Ira Sachs Sr.’s life. In non-chronological fragments, through footage spanning from the present day back to 1965, Sachs seeks to understand the complicated, unknowable figure of her father. In the end, the film doesn’t aim to be a comprehensive character study of Ira Sachs Sr.; Sachs realises that she has only so much access to her father’s mind, especially now that his declining health means that he can’t speak that much. Instead, she works with what she does have: access to herself, and to an extent, her siblings, to examine the bruises that a father leaves on his children, and how they attempt to heal.” Read the full profile.

16. John Ware Reclaimed (Cheryl Foggo)

From the introduction to our interview with Cheryl Foggo: “It’s one of Canada’s best kept secrets that there’s a rich history of the Black diaspora in the Alberta prairies dating back over a century ago. What little is known about that history has been condensed in the popular consciousness to the story of cowboy John Ware, an enslaved American who moved to Canada and became a successful rancher. But even the historical accounts of him are limited to a single book, John Ware’s Cow Country by Grant MacEwan, published in 1960, written by a white man, and full of racist stereotypes about Black masculinity. Cheryl Foggo’s moving, enlightening, and appropriately infuriating new documentary, John Ware Reclaimed, attempts to reclaim not just John Ware’s story from the biased history books but the history of Black Canadians in the prairies.

Foggo replaces Grant MacEwan’s mythology of John Ware with a newer, more modern, and more nuanced take, which highlights both Ware’s humanity and the very real struggles he faced. She casts real life cowboy Fred Whitfield as John Ware, and together, they create iconic images of a cowboy in action in the gorgeous Alberta landscape. Through animation, Foggo grants us access to the love story between John Ware and his wife Mildred. The animated images depict the two always hanging onto each other, almost curled together, as if sheltering from the storm of the wider world. Through original country songs written by Foggo’s daughter, Miranda Martini, as well as songs by Corb Lund, Foggo further sets the tone for John Ware’s story.” Read the full interview.

15. No Ordinary Man (Aisling Chin-Yee, Chase Joynt)

From the introduction to our interview with Aisling Chin-Yee and Chase Joynt: “The story No Ordinary Man tells is one of lost transgender history that’s finally being reclaimed. The film’s subject is Billy Tipton, an influential jazz musician who worked between the 1930s and 1970s. It wasn’t until 1989, when Tipton died in the arms of his son, Billy Jr., that Tipton’s family and the public discovered that he was assigned female at birth. After his death, Tipton’s story was twisted: Tipton was unequivocally a trans man, but the cis-dominated media presented him as a woman who dressed as a man in order to get a foot in the door in the music industry. Even the most cited text about Tipton’s life, Suits Me: The Double Life of Billy Tipton by Dianne Middlebrook, framed his story around this harmful narrative.

In Aisling Chin-Yee and Chase Joynt’s hands, No Ordinary Man is no ordinary biographical documentary. They go way beyond the standard archival footage and talking head interview approach to tell Tipton’s story. Joynt explained that “understanding that there was no moving image footage of Tipton was both a restriction and an opportunity for us to immediately start thinking creatively beyond the bounds of reenactment and other ways that biopics tend to be created.” The film features photos and audio recordings of Tipton, as well as his music, and his life story is told through the words of talking-head experts, most of whom are trans. But another huge part of the film are “auditions” where the filmmakers invite a whole host of diverse transmasculine actors to act out and then dissect scripted scenes from Tipton’s life.” Read the full interview.

14. Red Snow (Marie Clements)

One of the most inventive films of the year, Marie Clements’s Red Snow is part war film, part western, and part the story of the effects of colonialism. The magnetic and super talented Asivak Koostachin stars as Dylan, a Gwich’in soldier in the Canadian military who gets captured by the Taliban. This puts him in a bizarre position: he identifies as Canadian when he’s assumed as American, but as an Indigenous man, he doesn’t feel Canadian enough to be an asset worth rescuing for a ransom by the Canadian military. At the same time, as a soldier in Afghanistan, he’s somewhat serving as a force of colonisation whilst the Taliban is literally occupying the territory. This is rich territory for exploration, though in the early stages of the film, the dialogue often strays into cliche.

Still, the major achievement of Red Snow is the stunning visuals, which are paired with a non-linear narrative, which circles around memory, Gwich’in stories, and past romantic trauma. Working with cinematographers Robert Aschmann and Roger Vernon, and shooting entirely in Canada, Clements believably evokes the faraway places where the film is set. Though the film is particularly on point when in Dylan’s home territory, showing his connection to the land and snow. There’s a surreal, poetic quality to the storytelling, too, which feels more like Monkey Beach than any war movie I can think of, but then, this is Indigenous storytelling through and through. Despite its flaws, Red Snow is visually and intellectually inventive and is guaranteed to be unlike anything you’ve ever seen. AH

13. Flee (Jonas Poher Rasmussen)

From the introduction to our interview with Jonas Poher Rasmussen: “In the final shot of Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s beautiful, heartrending animated documentary, Flee, the animation fades into the live footage on which it’s based, and they’re remarkably similar. It’s a clever reminder that the story you’ve just been swept up in is in fact real, and a hint at just how faithful to reality the animation style has been throughout the film. Having seen some of the reference images on which the rest of the film’s animation is based, it’s incredible how true to life the film is.

Flee opens with silhouettes in gray and blue, an image of legs running, and the sound of heavy breathing. In voiceover, Rasmussen asks his dear friend, Amin, “What does the word ‘home’ mean to you?” It’s a strong distillation of the story the film will explore, of a man who has been constantly on the run, unable to find somewhere comfortable to call home, not just physically but emotionally, because he’s never told his story of fleeing as a refugee in full to the people who are closest to him. It’s also an introduction to the more abstract animation style that will characterise the moments of trauma that Amin recalls, more by evoking feelings than by faithfully depicting the facts of events.” Read the full interview.

12. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (Ryûsuke Hamaguchi)

From our interview with Ryûsuke Hamaguchi: “A young woman discovers that her best friend went on a date with her ex-boyfriend, which makes her wonder if she’s still in love with him. An aimless woman in her thirties half-heartedly attempts to seduce her old college professor, at the request of the younger man she’s sleeping with. A middle-aged woman attends her high school reunion in the hopes of reuniting with an old flame, but finds an unexpected connection, instead. Three short stories, loosely connected by coincidence, make up Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy. The film won the Silver Bear at the Berlinale — the festival’s second-most prestigious award — and deservedly so, as Hamaguchi’s beautifully written, elegantly crafted triptych is a melancholy delight.” Read the full interview.

11. The Dog Who Wouldn’t Be Quiet (Ana Katz)

From the introduction to our interview with Ana Katz: “The Dog Who Wouldn’t Be Quiet, the latest feature from Argentinian writer-director Ana Katz (My Friend from the Park), is a series of vignettes in the life of Sebastián (played by her brother, Daniel Katz) over the course of several years. Each vignette features small moments of connection, which taken together, feel like a full, rich life depicted in almost insignificant details. We see the moment when Sebastián is forced to choose between his day job and his dog; the moment he meets his future wife, but not when they marry; a moment of crisis as a father; and a moment of calm comfort that closes out the film. The moments are fleeting, but also often very funny and sweet.” Read the full interview.

10. Petite Maman (Céline Sciamma)

From our review: “In Céline Sciamma’s fifth feature, Petite Maman, getting to know your mother is like chasing after a ghost. Parents are elusive, in life and death, living in an adult world that, as a child, you only ever get to visit. The disconnect between parent and child is in the constantly moving camera of the opening scene, which follows eight-year-old Nelly (Joséphine Sanz) as she says goodbye to the many women in the hospital where her grandmother recently died, chasing the goodbye she didn’t get to have with her own grandmother. And in the first moment of stillness, when Nelly’s mother, Marion (Nina Meurisse), looks out the window of her mother’s room, at the grass and trees below, exhaustedly resting on a table, as if she might find her mother outside. As the camera pulls back, we feel the weight of Marion’s grief — and Nelly’s absence from the frame. They’re both experiencing loss, but it’s not quite a joint experience. Mother and daughter are moving at different speeds, in different rhythms. The camera reveals Nelly’s perspective, watching from behind, aware of her mother’s slumped physique, but unable to reach it.” Read the full review.

9. True Mothers (Naomi Kawase)

From our review: “True Mothers is the rare story of an adoption told from two perspectives and in two parts: first, the adoptive mother, Satoko (Hiromi Nagasaku), and then, the birth mother, Hikari (Aju Makita). Both women’s stories start before their son was born, and both women’s stories continue well after, until they meet again. Because Hikari got pregnant too young, at 14, her family is ashamed of her, attempting to hide the pregnancy altogether, and then expecting her to get over the traumatic separation from her child immediately. By contrast, Atoko was unable to get pregnant due to her husband’s infertility, a source of such shame for him that he suggests she consider divorcing him on learning of his problem. Their inability to get pregnant is a source of shame for both of them. This is magnified for all parties involved because Japanese culture strongly emphasizes genetic bonds, something Hirokazu Koreeda explored less effectively in Like Father, Like Son.” Read the full review.

Listen to our podcast episode about the films of Naomi Kawase.

8. Hope (Maria Sødahl)

From the introduction to our interview with Maria Sødahl, Andrea Bræin Hovig, and Stellan Skarsgård: “The week between Christmas and New Year’s proves a crucible for a married couple’s relationship in Maria Sødahl’s smart and sensitive drama, Hope. Unlike most dramas about cancer, the film is not about the initial diagnosis and treatment; instead Anja (Andrea Bræin Hovig) has already survived lung cancer, but just before Christmas, she discovers the cancer has spread, and surviving this is unlikely. The first bout of cancer is what kept the marriage together after a rough patch; the second diagnosis threatens to split them apart, as Anja starts to unleash all of her pent up anger — not helped by the medication the steroids she’s on, which alter her behaviour.

Throughout this tense but never sentimental film, Anja must reckon with the life she’s chosen and feels is about to lose, worrying most about how her passing will affect her children. At the same time, her husband, Tomas (Stellan Skarsgård) is going through an entirely separate journey: coping with what becoming a single father of six will mean, dealing with his wife’s lashing out without escalating things, and, of course, his own grief. They start on divergent emotional paths, but slowly find their way back to each other. Yet Skarsgård and Hovig imbue their characters with such history and love that even when they fight, you can feel the strength of their marriage and the weight of their years together. Their apartment also feels so full of history, from the books that line the walls to the bits of mess throughout, that you really believe they’ve lived here for more than a decade.” Read the full interview.

Listen to our podcast episode about Hope and Ordinary Love, two cancer dramas about marriage.

7. I’m Your Man (Maria Schrader)

From our review: “How big is the gulf between what we think we want from romantic relationships and what we actually need or would settle for? Is part of the joy of a relationship the knowledge that you’re needed? Is a flawed partner more attractive because they make you feel less alone for also being flawed? How do we change to suit our partners in a relationship? Wouldn’t it be convenient if you could store your partner in the spare room with the vacuum cleaner and the exercise bike? These are some of the many complex questions at the centre of Maria Schrader’s Berlinale competition film, I’m Your Man. In the film, cuneiform researcher Alma (Maren Eggert) is asked to test out a new AI robot, Tom (Dan Stevens), who has been designed to be her perfect man. For three weeks, he’ll live with her and learn from her, and at the end, she’ll write a report about the experience, evaluating what he’s like as a partner.” Read the full review.

Listen to our podcast about the sci-fi love stories of I’m Your Man and About Time.

6. Kímmapiiyipitssini: The Meaning of Empathy (Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers)

From the introduction to our interview with Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers: “Kímmapiiyipitssini: The Meaning of Empathy opens on a herd of buffalo grazing against the gorgeous landscape of the Kainai First Nation in Alberta. As we watch a mother and child buffalo nuzzle against each other, the soundtrack mingles a gentle score with the sounds of a woman speaking to a newborn baby. Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers’s Kímmapiiyipitssini is a documentary about the opioid crisis ravaging Tailfeathers’s own community of the Kainai First Nation. It’s fitting that a film that approaches that topic with such empathy and humanism doesn’t begin with sensationalised imagery of harm, but images and sounds of parental love and caring.

In Tailfeathers’s own words, “Kímmapiiyipitssini is this Blackfoot teaching that we give empathy and kindness as a means for survival.” In keeping with this teaching, her film advocates for the controversial practice of “harm reduction” as a more humane and effective way to treat those who live with substance use disorder. As Tailfeathers explains in voiceover, the most common practice of treating addiction is preaching abstinence, perpetuated by guidance like twelve step programs. But that simply isn’t realistic for many people addicted to strong and deadly substances like fentanyl, which entered Tailfeathers’s community seven years ago and has since caused countless deaths by overdose. Harm reduction advocates that patients be provided an alternative drug that’s safer and easier to regulate, so that they can continue their daily lives without painful withdrawal symptoms.” Read the full interview.

5. The Souvenir: Part II (Joanna Hogg)

When Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir came out in 2019, we loved the film so much we wrote an entire book about it and the making of it: Tour of memories: The creative process behind Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir. As a mostly autobiographical film about a bad romance that helped to shape Julie (Honor Swinton Byrne) as a filmmaker and person, it cried out for a second part: it left us wondering, what would Julie do now?

The Souvenir Part II is the perfect bookend, somehow even better than we could have imagined, telling the story of Julie coming into her own as an independent adult and a filmmaker. Structurally, it often mirrors The Souvenir, which began with a party in Julie’s flat where she was a wallflower who knew nobody; The Souvenir Part II closes with a party in the same flat, only now, everyone is there to see Julie, a whole community of support she’s built for herself over the course of these two films.

The Souvenir Part II explores Julie’s own attempt to deconstruct her toxic (yet formative in some positive ways) relationship with heroin addict Anthony (Tom Burke), which was the subject of The Souvenir, in the form of her film school graduation film. As Hogg puts it, The Souvenir Part II is a film about the making of The Souvenir: Julie builds an exact replica of her apartment on a soundstage, which is, of course, exactly what Hogg did for The Souvenir, only now we get to see what that set actually looks like in full. It’s a film about grief, growing up, making art, dealing with the misogyny in the film industry, and finding a place for yourself — which refreshingly, doesn’t mean finding a romantic partner. AH

Listen to our podcast episode about The Souvenir and The Souvenir: Part II.

4. Bergman Island (Mia Hansen-Løve)

Early on in Bergman Island, Chris (Vicky Krieps) declares, “I would like to have nine kids from five different men.” She and Tony (Tim Roth) are filmmakers who came to Fårö Island, the land of Ingmar Bergman, to work on respective projects. While they have a daughter together and often seem like a couple, Chris describes Tony as “a friend.” Hansen-Løve doesn’t define the specific parameters of their relationship, but demonstrates the differences in the way they each think about art and life. Chris envies and disdains Bergman, a prolific artist with nine kids from six different women. When she asks Tony how he feels about Bergman’s lack of involvement in his kids’ lives, he responds, “I should feel bad, right?” This is the crux of the film. Chris (and Hansen-Løve) thinks deeply about her responsibility as an artist and parent, along with the gender-based limitations she faces; so much, in fact, that those themes are prevalent in her own art. Tony, on the other hand, is not burdened in the same way. Like Bergman, his work revolves around women sans any of the complications they actually face.

In the second half of the film, Chris asks Tony for feedback on her screenplay. As she describes it to him, the film melts into the world of her work (which also happens to take place on Fårö). Her protagonist, Amy (Mia Wasikowska), is a film director who is in town for a friend’s wedding along with her ex-boyfriend, Joseph (Anders Danielsen Lie), whom she still loves. Like Chris, Amy has a young daughter and a partner back home, but her identity is not completely wrapped up in those relationships. In another striking similarity to Chris’s life, Joseph reveals that Amy “wanted two children with two men at the same time,” a desire that he found “absurd.”

As the screenplay develops, the autobiographical resemblance becomes undeniable. Chris uses her work as a lens through which to view her own life and perhaps, so does Hansen-Løve. Women don’t have the luxury of shirking their parental responsibilities to focus solely on creative endeavours; however, they have the ability to examine their unique experiences and turn them into art. Lindsay Pugh

Listen to our podcast episode about Mia Hansen-Løve’s Things to Come and Bergman Island.

3. Charlatan (Agnieszka Holland)

From our review: “Polish filmmaker Agnieszka Holland (The Secret Garden) has followed up her biopic of Gareth Jones and his discovery of the 1930s Ukrainian famine, Mr Jones, with Charlatan, a post-war biopic about Czech herbalist and healer Jan Mikolášek (1889-1973). While Mr Jones was about revealing an untold harrowing part of history and how one foolhardy man brought this story to light, Charlatan uses Mikolášek as a sort of metaphor for post-war communism in order to ask whether the new regime is really a form of liberation or just a variation on a fascist theme.

Holland introduces us to Jan (Ivan Trojan) as a successful, middle-aged man, who runs a healing centre out of his mansion. Every day, hordes of people queue up in front of his home with clear bottles of urine in hand, hoping for a chance to see the great healer and find hope. Jan’s methods are to hold up the clear bottles of urine to the light in order to divine diagnoses ranging from diabetes to kidney failure. We never see him follow up with patients so the accuracy of his proclamations aren’t really up for debate. Instead, we see him sell one of four brews to each of his patients as cure-alls, and watch people leave excited and satisfied.” Read the full review.

Read Alex’s career profile of Agnieszka Holland.

Listen to our podcast episode on Agnieszka Holland’s films.

2. The Worst Person in the World (Joachim Trier)

From our review: “In any other hands, and perhaps any other time, The Worst Person in the World would centre around Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), the sometime boyfriend of Julie (Renate Reinsve), the film’s actual protagonist. While remaining largely in the background of the film, Aksel pens a comic, gets a film adaptation of his work, loses the love of his life, goes off on cancel culture on the radio, and then has to reckon with his mortality. But since this is a Joachim Trier film, which, like all his films, was penned with Eskil Vogt, the driving engine of the film is not plot; instead, it’s a cinematic exploration of a more passive character’s emotional and intellectual experiences.

Most of Julie’s plot occurs within the film’s five-minute prologue: she switches fields of study from surgery to psychiatry to photography; has as many love affairs as career changes; and culminates by meeting Aksel, with whom she has a rom-com-esque meet cute before falling in love and moving in with him. What follows is the harder part: dealing with the consequences of your choices and finding the courage to keep making choices, to combat the passivity and complacency that it can be so easy and comfortable to fall into.” Read the full review.

Sign up for updates on our upcoming ebook on Joachim Trier’s films.

Read our comprehensive guide to the films of Joachim Trier.

1. Quo Vadis, Aida? (Jasmila Žbanić)

From our review: “It was a while into the first scene of Quo Vadis, Aida? before I realised that Jasna Ðuricic’s fierce lead character, Aida, was a translator. Facilitating a discussion between the mayor of her hometown, Srebrenica in Bosnia, and a pair of Dutch UN soldiers, she spends the scene simply relaying the words of the men in the room, but Ðuricic makes her opinions of the men’s decisions so clear that she could easily be mistaken for a participant. She shifts in her seat, her gaze set in a worried scowl, her eyes shifting restlessly between everyone in the room. She and the mayor exchange knowing looks as if silently communicating. When she translates, she speaks quickly in a stern tone, rushing the conversation along because she knows how urgent the matters being discussed are. Impartial translation is pretty much impossible in any case — you’re always adapting words and phrasing through your own lens — but especially for Aida, a citizen of wartorn Srebrenica.

This is 1995, in the heat of the war between the Serbian and Bosnian populations, and the Serbs are encroaching on Srebrenica in increasingly violent ways. Writer-director Jasmila Žbanic, who lived through the war, drops us straight into the action with this scene of negotiation between the mayor, who is concerned for the safety of his townspeople, and the UN soldiers, who assure him that the Serbs “have been issued an ultimatum” that will keep Srebrenica safe. Through Aida’s panicked eyes, we watch this hopeless conversation unfold as the soldiers naively reason that the Serbs won’t attack because the UN has warned that they will face “serious consequences” if they do.

This is the prologue to Quo Vadis, Aida?, a harrowing retelling of the genocide of the people of Srebrenica that grapples with the complicity of those who were ‘just doing their job.’ Although the film is brutal and disturbing, it refrains from showing us the most violent acts of the genocide, like the rapes and beheadings. Even when the mass genocidal slaughter occurs at the end of the film, Žbanic shows us the guns firing but not the bodies hitting the floor. She’s interested in who holds the power, not the spectacle of their violence.” Read the full review.

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch films like the best films of 2021 at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.

Click here to subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter.