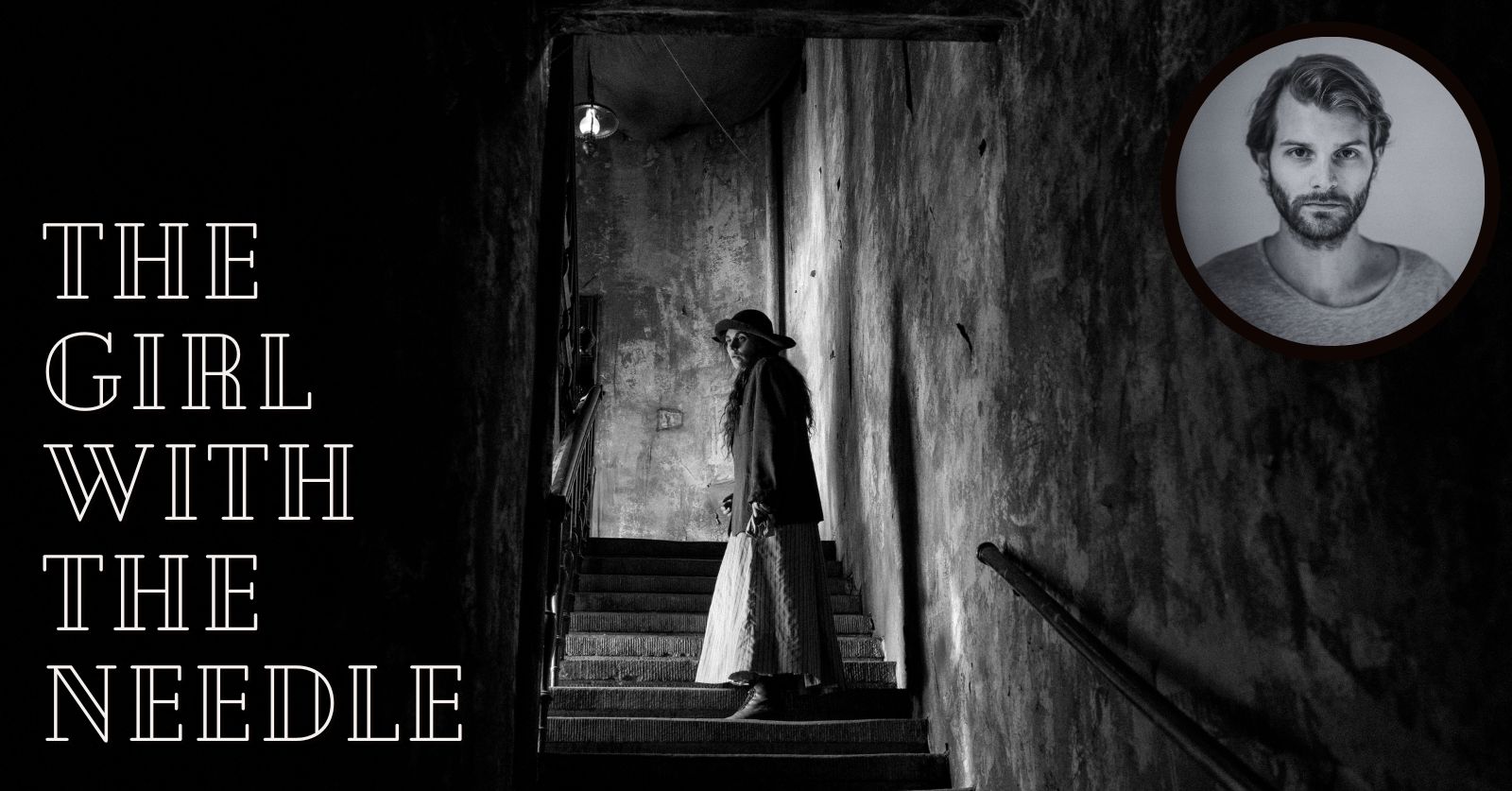

We interview filmmaker Magnus von Horn about his Golden Globe Nominee and EFA-winning film The Girl with the Needle.

Listen to the interview with Magnus von Horn on The Girl with the Needle as a podcast.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

“We set out to make this black-and-white film set 100 years ago,” Swedish writer-director Magnus von Horn told me of his new feature, The Girl with the Needle. “When we enter a film like that, we feel we’re fairly safe because this takes place a long time ago, and it’s not even in colour.”

But the world of The Girl with the Needle is a sinister one, where husbands can disappear in the war without a trace, and you can be thrown out of your home or your job with a moment’s notice. In some ways, it’s a world very distant from our own. But von Horn and co-writer Line Langebek find chilling parallels with the present day, where women’s reproductive rights are still under threat and capitalism is no less cruel. It makes for a punishing but rewarding film, one of the year’s hardest watches and also one of its very best.

The origin of the title The Girl with the Needle

The film follows Karoline (Vic Carmen Sonne), a seamstress in a factory whose husband has recently disappeared in WWI and left her destitute: the film opens with her being thrown out of her apartment. When she begins a relationship with her boss, who feels for her plight, she soon falls pregnant and finds herself completely alone and jobless, too. Desperate, she arrives at the women’s bathhouse with a needle in tow, ready to abort.

As she begins bleeding profusely from the needle, a stranger, Dagmar (Trine Dyrholm), intercepts her attempts and cautions her that she could die from this. Instead, Dagmar proposes to help Karoline by finding the baby a new home once it’s born as part of an underground business she runs. Soon, Dagmar takes Karoline into her employ, and the women begin to live together.

But how does Dagmar find new homes for the babies? The story she tells Karoline sounds like a fairytale, especially once we hear it for the second or third time. Indeed, the setup for the film borrows from fairytales: Dagmar is a middle-aged woman, you might say a ‘witch,’ who owns a candy shop, where she lures desperate young women with the promise of help. Dagmar’s home and shop are dark, Gothic spaces. But then, so is the rest of the world. As von Horn explained, “We exaggerated the setting completely, throwing dirt, water, and smoke on the exteriors. We played with perspective a lot in some of the interiors, where we sense it, but we don’t start paying too much attention to it.”

Setting the context for the characters’ stories in The Girl with the Needle

Based on the true crime story of Dagmar Overbye, a Danish woman who helped women like Karoline, The Girl with the Needle is less an indictment of Dagmar than the society that produced her. The film is rich in the details of the precarity of Karoline’s life. She begins the film in a shabby apartment and a tough job but soon loses both: moving to an attic with a massive leak and unreliable gig work that involves hard labour.

This disappearance of her husband in the war is both the cause of her problems and an opportunity: she can trade up with a better suitor. Karoline is always on the lookout for ways to improve her situation, no matter who she might hurt along the way. Just as often, she’s the victim of other people’s ambition, pride, or carelessness. And she’s not the only one.

Throughout his career, von Horn has told stories of complex people who are often treated as disposable within the society where they live. In The Here After (2015), a whole community is ready to write off a teenage boy for the worst thing he did as a child. In Sweat (2020), a social media influencer is terrified of getting off the treadmill of content production lest she become yesterday’s news, another disposable online icon. Both films were as much about the sometimes unlikable characters as the societies that abandoned them. And the same is true of The Girl with the Needle.

Magnus von Horn previewed The Girl with the Needle for us in our 2021 interview

For von Horn, it all comes down to empathy. In 2021, he told us, “If you show a character as a human, then you stop treating the character as a victim or a perpetrator. If you can love your character, then you will love the good and the bad. I’m really attracted to the dark side, but also to the good side. I like both.“

With The Girl with the Needle, von Horn told me, “We wanted to make a film that is on the edge between drama and horror and plays with the audience’s expectations.” Social realist in its concerns and attention to the human drama produced by a cruel society, the film is a heightened period drama that borrows from the conventions of horror. It even explicitly references horror movies from the period.

Before the film’s North American release, I sat down with Magnus von Horn for an interview via Zoom to discuss how he walked the line between drama and horror in The Girl with the Needle to make a film that’s social realism with a twist. He discusses being inspired by German Expressionism and Batman and crafting a story that is more modern than it might initially seem.

7R: A few years ago, you spoke to Seventh Row about Sweat, and you described your next film as a horror film and a costume drama, which is now The Girl with the Needle. How did you think about the film as a horror film?

Magnus von Horn: I have always wanted to make a horror film. When I was approached to develop this project, I felt that it had the potential to be a horror film. I never wanted to make a horror genre film but to somehow explore what a horror film is. How can you base it on drama, and always stick to the characters?

I think genre film is genre because the form and the structure of the film are stronger than the characters within it. That’s when genre wins. But once the characters become stronger than the genre, the genre somehow disappears. So, it’s difficult to call all good genre films genre films because the drama is so strong inside. They become a kind of a mix, like The Shining. I wanted to make a horror film, but to focus on the character and the drama.

7R: How did that affect your thinking about the film’s aesthetic or even the story or the approach for The Girl with the Needle?

Magnus von Horn: There was this true story of Dagmar Overbye. It’s like a true crime story from Denmark set during the time of WWI, and just after. It was a really horrible story. But when we started researching it, we learned about the society surrounding it, that would cause women to give babies to Dagmar. It says a lot about that society.

We wanted to make a story with a relatable main character. So we didn’t want to pick Dagmar as the main character. We went into this world of fiction and developed the story of our main character, who is one of the mothers who gives her child to Dagmar. Her story reveals a lot of social aspects of the world she lives in, which puts her in a difficult position which is why she ends up at Dagmar’s place.

“Those difficult circumstances are also like horror because it’s a horrible world.”

Those difficult circumstances are also like horror because it’s a horrible world. We knew that we didn’t want to make a purely social realist film but to approach that world in a creative way. We were inspired by films made at that time, or images of that time, and trying to recreate that world using elements of German Expressionism, which are like horror movies from the time.

When we eventually enter Dagmar’s very dark apartment, the film meets horror. We wanted to make a film that is on the edge between drama and horror and plays with the audience’s expectations. It has a different kind of structure, and we don’t know what to expect about where the film will take us.

Magnus von Horn on a modern approach to period drama The Girl with the Needle

We have to be very aware of what the audience expects when we give them certain things. We set out to make this black-and-white film set 100 years ago. When we enter a film like that, we feel we’re fairly safe because this took place a long time ago, and it’s not even in colour.

But eventually, the story may not be so far away. It’s more modern in its approach, and all those things are a kind of a game with the audiences to try to tell something in an interesting way.

The real story it’s based on is about a woman who does this [redacted horrible thing]. But she did it for a reason. That reason starts making sense in a strange way. It’s like, is she the horrible one? Or is society the horrible one? Is the society averting their eyes from real horrors? It creates a very complicated image full of drama, interpretation, and contradictions.

7R: If the film is an indictment of something, it’s not necessarily an indictment of Dagmar, but of the society around her that produces the conditions that require her.

Magnus von Horn: Completely. Initially, we said, half jokingly, it’s like when the city of Gotham can’t deal with its crimes, Batman comes — or Joker comes. In this version, Dagmar comes. It’s not so different, except this happened for real. We can’t just call Dagmar a sick woman. She’s part of something bigger, just like you said, the society around her,

7R: People are so disposable in this world. Karoline’s husband just disappears, so she’s planning on trading up husbands. And even when he returns, she throws him out because she has a better option. She gets thrown out of her job so quickly. Your earlier films are also about people who society treats as disposable.

Magnus von Horn: Yes! It’s great that The Girl with the Needle is set in a world 100 years ago. The world looked different. When you are in this world, when you are thrown out, it’s not like, “I need you gone by the end of the week.” It’s like, “You have five minutes.” It sets up a different mindset, which is a reflection of a harsh world, an oppressive world. When your husband comes back, you throw him out directly. You go for another romance because that’s probably more fruitful in this world. You hope to improve your situation from peeling potatoes in a horrible attic.

It creates a different mindset and different behaviours. Working in this world is fun and provocative because you must think with a different logic. For example, breastfeeding a seven-year-old girl: today, it’s really provocative. But in the universe of the film, it might not be such a strange thing to do. It’s great for her immune system. And the milk needs to keep flowing.

We can be judgmental about it today if it happened now, but we don’t really have the right to judge them in their society because they lived in a different world. It’s interesting how the world is very different in some ways, but the world is still similar. It’s still us; it’s not so long ago, actually.

7R: How did you walk that line with The Girl with the Needle? Period dramas are always at their core about reflections of society today, even if they’re about the past.

Magnus von Horn: We need to create a world that feels, on the one hand, extremely credible and realistic, but on another level, it also should feel like a creation and an imagination of the world 100 years ago.

I always thought Oliver Twist from 1948 by David Lean is such a great film because it has all this strange architecture and this really created world. But it’s also a very social realist story. It mixes very credible acting and this world that feels a bit twisted. I think film loves this contradiction, these contrasts.

But it’s about having a sense of when it’s being exaggerated and when you’re falling off the fence. I built up a good nose for that because we developed the film for so long. We have a good sense of what the DNA of this film is: when it becomes too much and when it’s not enough.

7R: What did you want to be heightened or exaggerated in The Girl with the Needle?

Magnus von Horn: It’s many different things. When I was writing or doing prep for the film, I was always listening to electronic music. I always knew I wanted the soundtrack not to be from the time but to have an electronic bass. Now, I see that this makes the film more modern and more connected to the world today.

Black and white is a way for us to make a credible time journey for the audience by using images that are inspired by the images, films, and photography from that time. When the workers leave the factory in the film, we recreate a frame of a Lumiere Brothers’ film. It’s a way of making the audience travel in time and believe that world. Even if they don’t know that particular image, subconsciously, I believe they feel it.

I’ve always wanted to build miniatures to use in a film. We built thirty or forty miniatures of buildings and filmed them. We scanned them and added them digitally to the film with VFX. It was a half-analog way of working.

Magnus von Horn discusses creating a heightened reality without becoming Tim Burton in this interview

When I was working with cinematographer Michal Dymak, it was about being as creative as possible without becoming Tim Burton. For example. the camera should never be able to do completely unrealistic things. That was something we worked on a lot. The camera should not be able to just go and fly through windows and do all this magical stuff. We should treat the world as completely real regarding the camera.

But the world should not look completely real. We can play with the scenography, but the camera should treat the world as real and not be exaggerated.

The setting is completely exaggerated: we threw dirt, water, and smoke on the exteriors. We played with perspective a lot in some of the interiors, where we sense it, but we don’t start paying too much attention to it. It’s a fine line to walk.

7R: You mentioned playing with perspective in the interiors. There’s sort of a gothic element to a lot of the spaces.

Magnus von Horn: We built sets for most of the interiors: Karoline’s apartment in the attic, Dagmar’s candy story, Dagmar’s apartment and the back room where Karoline sleeps. We deliberately made the corridors a bit too long and very narrow. There are very, very thick boards for the walls in the back room. It warps the perspective alongside the small staircase. We also used a lot of wallpaper. If you look at the locations we had in colour, they’re all red and green because those are the colours that make for the most interesting blacks and grays.

We would try to find locations that would also play with perspective and give depth. We wanted a sense of buildings that are a bit crooked, like almost falling over. Any chance we had, we would try to work with that to a certain extent. In the film, there are a lot of VFX shots, but you don’t notice it because you don’t see it.

7R: You shot The Girl with the Needle in the academy ratio. How did that help?

Magnus von Horn: The academy ratio is a 3:2 aspect ratio, which is the aspect ratio of photography at the time. We prepared the film by taking stills in that aspect ratio. The cinematographer, Michal Dymek, would take stills, and I would act in them. That’s how we do our storyboards. We would always shoot in the 3:2 aspect ratio when we scouted for locations.

It’s also about using the frame from that time to travel and to use the references of images and films that we know represent that time. But those are not copies of what the world looked like at the time. It’s just other images that someone has very consciously made and taken of the world, which they’ve deliberately framed to look more beautiful or scary than the real world. It’s like a double meta level in this process, which is very inspiring.

More Magnus von Horn interviews, The Girl with the Needle, and horror

Listen to our podcast on Magnus von Horn’s first two films: The Here After and Sweat.

Listen to this interview with Magnus von Horn on the podcast.

Read our interview with Magnus von Horn about Sweat.

For more films on the border between drama and horror, check out our ebook Beyond Empowertainment: Feminist horror and the struggle for female agency. The book features in-depth studies of films like Personal Shopper, Thelma, and Unsane.