Co-directors Sofia Bohdanowicz and Deragh Campbell discuss finding the structure of MS Slavic 7, their collaboration, and working on a budget.

“And the funereal earth was bursting

This was our first encounter

The next will take place on Judgement Day.”

‘To Józef Wittlin on the Day of his Arrival in Toronto – 1963’, Zofia Bohdanowiczowa translated by Jagna Boraks

MS Slavic 7 opens on the scanned page of a book open on this poem. The pages are yellowed but crisp. The thin, semi-translucent pages hint at poems printed on the reverse side. On the left, Bohdanowiczowa’s poem is written in Polish, on the right the translated English. The spine is bound tightly in tiny, delicate loops. The delicate quality of the page does little to dull the intensity of the emotions they express.

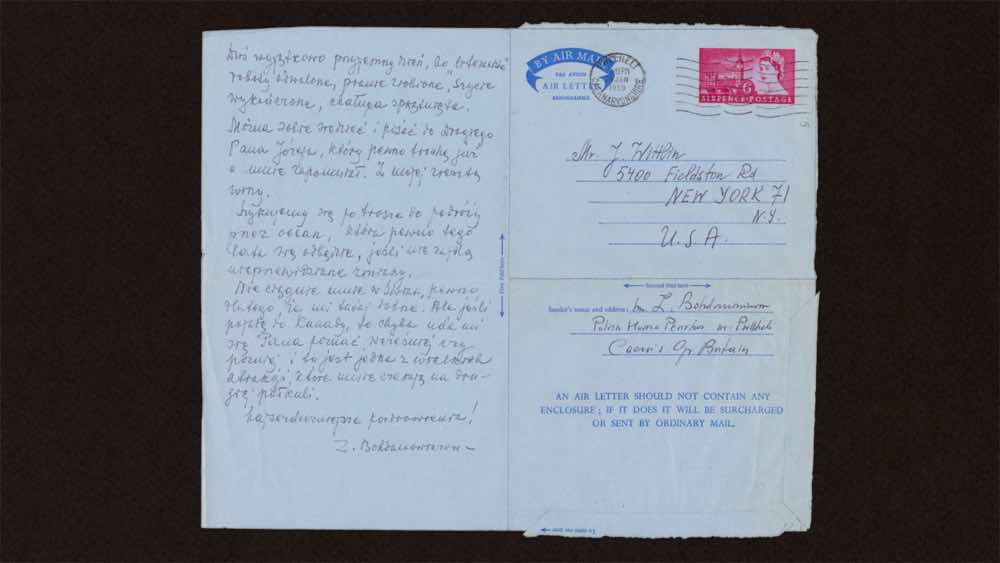

The newest collaboration between Sofia Bohdanowicz and Deragh Campbell (who starred in Anne at 13,000 Feet) is a feature-length examination of letters written by Bohdanowicz’s grandmother, Zofia Bohdanowiczowa, to another Polish poet, Józef Wittlin. Set over three days, Campbell reprises her role as Audrey, a character who has already appeared in their previous collaborations Never Eat Alone and Veslemøy’s Song (currently streaming on Mubi). Audrey is something of an alter-ego created by both Campbell and Bohdanowicz, combining different elements of themselves.

Audrey’s family is central to the film. Her grandparents were Polish immigrants who immigrated to Canada after suffering during World War II. The letters are actual letters written by Sofia Bohdanowicz’s grandmother to the poet Józef Wittlin (in the film, Zofia Bohdanowiczowa becomes Audrey’s great-grandmother). As a film about generational disconnect, it is unsurprising that one of the other main characters, Anya (Elizabeth Rucker), steps in as Audrey’s aunt. She represents a generation who grew up in a home of first-generation immigrants. Aside from Audrey’s aunt, the other characters are an archivist (Aaron Danby) and a translator (Mariusz Sibiga).

The film is divided into three parts. Over three days, Audrey returns to the Harvard archives to read her great-grandmother’s letters. At the end of each day, she has a long, thoughtful monologue explaining her thoughts and progress, addressed to the camera. Each day, ideas evolve, but the letters do not necessarily bring Audrey any closer to her family history.

Intimate and reflective, the film examines the threads that bind us to our family histories. What happens when those lines are frayed? What place do we have within that lineage? The film is an examination of personal histories, language, and objects. As Bohdanowicz explains, it’s about finding “the macro through the micro.”

Sofia Bohdanowicz and Deragh Campbell joined Seventh Row by telephone to discuss the film’s production and their collaboration. MS Slavic 7 opened at TIFF Bell Lightbox on October 10.

Seventh Row (7R): When did you guys start working together, and how would you describe your working relationship?

Sofia Bohdanowicz: Deragh and I started working together when I was working on my first feature film called Never Eat Alone. I had accumulated all of this footage of my grandmother working through all these domestic movements and gestures that I later studied in Maison du bonheur. I had spent a lot of time filming with my grandmother and my partner Calvin’s grandfather, George, and I wasn’t really sure how this narrative line would come together. I had this narrative of my grandmother wanting to get in touch with someone that she had been in love with in her twenties, but I didn’t know how to recreate or stage these moments in film with myself.

I realized that it would be really interesting to have an actor re-animate these moments and these conversations that I had with my grandmother. I had seen Deragh in I Used to Be Darker directed by Matthew Porterfield. I was really touched by how genuine, authentic, and honest her performance was, but I also knew her from going to a lot of screenings in the city [Toronto] at the Lightbox. One day, I finally asked her if she’d be interested in working with me for Never Eat Alone. It was just such a seamless experience. Our chemistry was fluid from the moment that we started working together.

We moved forward, and we made Veslemøy’s Song, and MS Slavic 7. And we have another short that we just finished. This character, [Audrey], that we developed together, are pieces of myself and Deragh and pieces of family members. She has really taken on a life of her own.

Deragh Campbell: Our dynamic is quite particular. We have a common goal to discover something authentic in a moment. Two perspectives are better than one: you have someone behind the camera seeing what’s happening and someone in front of the camera, seeing what’s happening. We never have any issue deferring to the other person or feeling that we have to defend something as our idea. It’s very much [working towards] what’s best for the film.

As a performer, I’ve always found that Sofia is really non-judgemental. You have none of that dynamic that can sometimes happen between an actor and director where you feel that you have to please them, and you’re either failing or succeeding. This was true even before it was a co-direction; it was always a non-hierarchical model between the actor and director.

Deragh Campbell stars in Anne at 13,000 Feet

Read our interview with director Kazik Radwanski

Sofia Bohdanowicz: What you said there is really intelligent and wise. Maybe you said it before, but I feel like this thing about me being behind the camera and you being in front of the camera creates this fluidity in the way that we work. There isn’t a lot of ego. It’s not one person being right or one person being wrong. It’s about looking at the overall goal and trajectory of the work together.

7R: How did your collaboration work in the screenwriting process for MS Slavic 7?

Deragh Campbell: Each scene is approached in a different way. For instance, the party is totally unscripted and improvised. But the interactions with Anya, that were actually shot at a different time in the same location, those are totally scripted. The interactions with the archivist are scripted.

But the monologues are kind of somewhere in between. Sofia had read the letters previously and written notes about what she thought was important. I had filled up a notebook with some secondary sources, like poetry and art criticism and things that I thought could be relevant. At the end of each shoot day, I would read one third of the letters, then sort of compose a monologue based on Sofia’s notes, my notes, and my first impressions of the letters. I’d sort of write a monologue and then not recite it verbatim, but improvise within those ideas that I had jotted down.

Within those kind of time constraints, you get that impression of connecting thoughts and connecting sources. It was also an interesting mode of characterization in that we found a way to make a character that represents both Sofia’s and my ideas in that moment.

Sofia Bohdanowicz: Our thoughts were fused within the film in a very intuitive way. What’s hysterical is that we just won an award for best script at the Black Canvas Contemporary Film Festival in Mexico. I picked up the award, and I wanted to say, “There was no script!” But then, I was thinking about it, and I was really moved that we won that award because I think that it points to how strong the structure was and how constructed Deragh’s ideas were in approaching the film. It also honours my great grandmother’s work in her words — which we kind of exhumed, reanimated, and brought to life together.

I discovered the letters, and I was really excited about the content. Deragh was just as excited about the content as if it were her own great-grandmother. She took it upon herself to pitch this beautiful structure of this woman poring over these letters over the course of three days. That was the foundation of the film. I very much see her as an architect of thought and conversation and ideas.

The only thing I would add about the scenes that were scripted, like between Aunt Anya and the archivist, is that we built upon what we did in Never Eat Alone: for each scene, there would be beats and certain things that Deragh and my grandmother had to hit within the scene, but it was largely improvised. They were coming up with their own dialogue. With this film, we grew from this idea. We had a structure, but we weren’t exactly sure about the conceptual narrative, which came through within the editing process.

7R: I read that an early version of MS Slavic 7 did not include subtitles during the sequences where Audrey is reading the letters. Can you explain why you decided to add them?

Sofia Bohdanowicz: The original idea of having those segments silent was it was the idea of deconstructing the letters. First, you have the image of them. Then, you understand them through Audrey’s interpretation of them. At the end, you get the recital of the letters.

It was during note sessions where we were talking about the narrative within the letters and what it meant to us that we realized that it was kind of a shame to not have that narrative throughout. The monologues are about the pleasure of reading, the pleasure of forming these connections and these new thoughts. Without us even having anticipated it, it was becoming a kind of a survey of different ways of reading on screen. You ask the audience to read in different ways. I was really excited by the different ways that we could explore a letter or bring it to life.

At the Black Canvas Festival in Mexico, they were really curious about the subtitles, as well. Something that came out of conversations there is that she’s [Audrey] looking at these letters, and she can’t understand the content because she doesn’t speak Polish. I don’t speak Polish either. But we were trying to explore the weight of the history that has preceded this person and still weighs on her. Does it still impact her in the here and now?

I was reading an interview with Chantal Akerman where she was talking about her fiction work, and people were asking her if it was autobiographical. She said, “Well no,” but she was incorporating [autobiographical] elements into her fiction films like Rendez-vous d’Anna which was a big influence for us when we were conceiving this film. She said that, naturally, there were themes from her own life that were inserting themselves into the narrative of Anna which were more documentary-like than a documentary could ever be [but it was still a work of fiction].

That’s the same for Audrey in this film. In some ways, she’s exploring her great grandmother’s work and trying to understand her own history. But she’s also attracted to things that reflect her own reality, as well.

7R: There’s also a lot of exploration of the tactility of the letters themselves. Can you talk about that?

Sofia Bohdanowicz: Within the structure, there are three elements that were really important to us. The first day is all about the objects. What does the object look like, feel like? What does it smell like? How does it sound in your hands? I got a macro lens, and we did a lot of principal photography where [Audrey] was just engaging with the objects.

I remember the first day that we went to camera: we worked in silence for 30 minutes where [Audrey] was just touching and engaging with the letters. It was just this seamless moment where I was actually capturing Deragh interacting with these objects in a very meaningful way. So there is something very documentary-like about it.

The second [idea] that Deragh wanted to explore in the structure was the aura of the objects and the spirit of the object. [Treat the letters as a kind of] talisman that has kind of magical properties that you can hold onto because of its history. And then the third part was the content. We were really trying to find an interesting way to chronologically feature the story of just Zofia and Joseph interacting with one another.

7R: Do you want to talk a little bit about the relationship between language and learning about family history? There’s a literal disconnect in the languages spoken between generations, but a more spiritual one, as well.

Deragh Campbell: I have a lot of faith in language and its ability to, with some difficulty, of course, articulate how you feel. Audrey wants to be close to her great grandmother, and she wants to experience the significance of the letters, but it is a little bit difficult. She can’t just look at them and fully emotionally experience it. She has to engage with language in order to be able to find meaning in it. She has to relate to [the letters by reading] theoretical writing. And through that kind of engagement with language, she’s actually able to feel the reality of the letters more.

Sofia Bohdanowicz: There isn’t a way for me to absolutely see eye to eye and understand in any way what my great-grandmother survived, nor my grandmother [who immigrated to Canada] nor my father, growing up in Toronto with parents who had survived World War II. I love the way that you [Justine] highlighted how different generations speak different languages. There are generational gaps, and that’s something that we really wanted to work on, explore, and highlight. Within the film, you see Audrey striving to connect with her great-grandmother’s work [as a way] to understand her own family history so she can situate where she is herself in the world. But there’s also this dissonance between herself and the parental generation.

My grandmother was put in a camp in Siberia, and my grandfather fled and lived in various places throughout Europe during World War II. When my father was growing up, he had parents that survived that. My Polish grandparents wanted, very simple, comforting and basic things. They wanted to make a soup. They wanted to know how school was going. They just wanted to provide an environment where people could eat and exchange ideas and had a very practical approach. They wanted my father to get a steady job: don’t be an artist because that will not give you a solid income. [They] look[ed] at [his] art as a hobby.

So that’s what my father learned from his parents: have a solid job, have a stable life. Those were my grandparents’ values because of the trauma that they survived. My father wanted to pass that on to me. I feel like that is a dissonance that exists within my engagement with my parents. I’m not mad at them for it; I don’t resent them for it because I see that as an act of love. They’re just trying to pass down what they know best to me.

The other thing that is highlighted in the engagements that Audrey has with Anya is that [Anya] represents this kind of dissonance between these two generations, but she also represents self-doubt and insecurity. As artists who are trying to self-actualize and assert themselves in the world, sometimes, there are a lot of difficult and abusive things that we say to ourselves when we’re trying to come through on our own ideas and create something. That was something that was teased out of those interactions, as well.

Audrey can be a little bit of a brat sometimes. She’s saturated in her own privileged perspective. Growing up, she didn’t have to experience what her grandparents experienced. You didn’t have to experience the trauma of being a child of parents that survived the war. That is another factor, another layer, that impacts her inability to communicate to those generations. She’s so saturated in her own perspective, just in terms of not having lived that history, but trying to understand it. She’s unable to completely connect to it because of how privileged she is.

7R: MS Slavic 7 is very cyclical. And I feel like this impersonal domestic space of Audrey’s hotel also kind of goes through that transformation over these three days.

Deragh Campbell: Some of the way that we shot the film was fairly unconventional. Usually, you get one location, and you shoot everything there, and then you move to the next location. Whereas with this, for those monologues, we would return to Union Cafe each morning and record one of the monologues, and then go on with the rest of the shoot day [at a different location]. [Returning to Union Cafe each day] was a part of being able to show them [the viewer] the process of her thoughts. We found that necessary.

The hotel is a bit different. That was shot in the more traditional way. We shot everything that took place in the hotel in the one day. That’s a budgetary thing, and I’m so glad we ended up getting the hotel room that we did. I love the splashes of turquoise. It was like a slot machine of art direction. We went on Hotwire, and it was really whatever room we got.

Sofia Bohdanowicz: I was like, “Can’t wait to see what this is, what the images in our movie are going to be.”

Deragh Campbell: I love hotel rooms. I’m a little bit obsessed with them. When you enter a hotel room, you have this neutral space. It gives me this intense sense of possibility. I feel like I could write a novel in a hotel room.

I love that every day, [Audrey] comes back to this neutral space, and it is full of new information and new inspirations. I love this idea that a hotel room is a place where your thinking is so uninterrupted by cumbersome symbols of your day-to-day life. It’s so different returning to a hotel room.

At film festivals, when you’re returning your hotel room after seeing three movies, you just feel the movies kind of taking up that whole space for you. Whereas it’s different when you returned to your home, and you see your photographs, your books, and all these things. It doesn’t feel quite as purely just like an experience of that time and that material that you were taking in.

Sofia Bohdanowicz: In the same way that Audrey is trying to come into her own, she’s trying to make these spaces her own. What I love about working with Deragh is that she really thinks about the details of her [character’s] wardrobe and the objects that she’s going to interact with.

When we were preparing to do the shoot, she prepared this reading list for herself. This is something that she does frequently for a lot of characters that she prepares for her. She has like a curriculum that she follows to prepare for a character, which I think is absolutely brilliant.

We were curating these objects that she would use in the film. It’s such a funny way to set up the film: she walks into a hotel room; she has her bottle of wine; she has her books, and she wants to put her clothes away. There’s something really beautiful about examining these little details as a way of looking at how we get from here to there, like as a whole. That’s a theme that also runs in Akerman’s work, documenting these everyday gestures to understand the truth: the macro through the micro.