Seventh Row’s editors reminisce about six of the best scenes of 2020 and explain why they stuck with us throughout the year. This is the final article in our 2020 wrap up series.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

For the final piece in our best of the year series, we wanted to look back on the moments in 2020 films that have stuck with us. Three of our writers picked a few scenes each, so we’ve come up with six in total — a small sample of many memorable moments that defined our year.

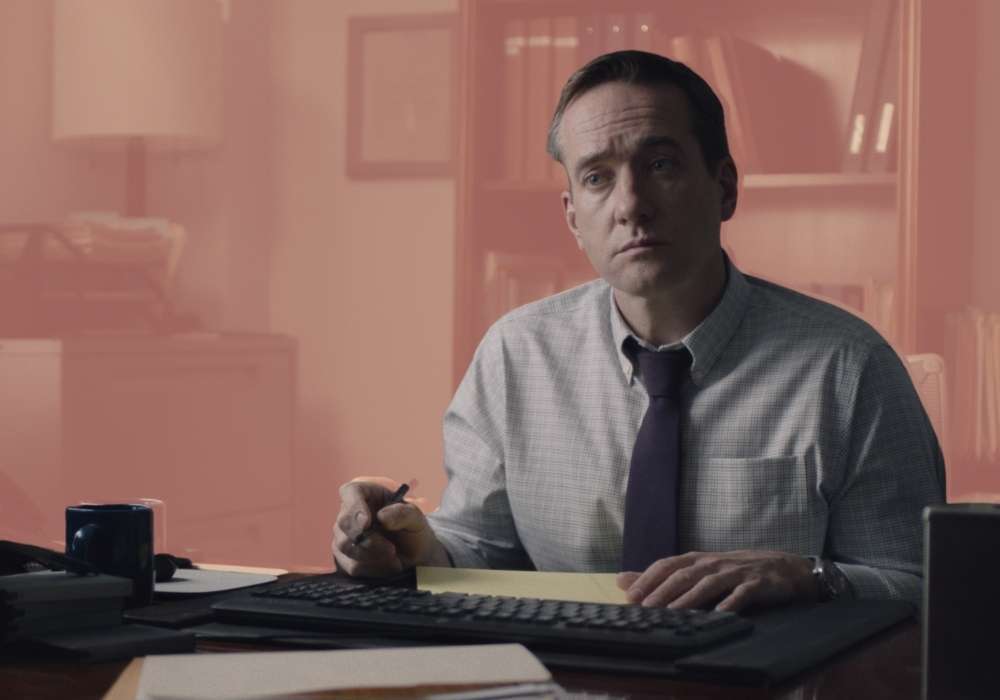

Visiting HR, The Assistant

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the brilliance of Matthew Macfadyen’s one-scene performance in Kitty Green’s The Assistant. Here’s a short excerpt from that article (read the full thing here): “He plays an HR consultant who appears mild mannered, kind, and helpful until you realise that he’s doing his part to cover up sexual abuse in the workplace. This scene, which takes place 50 minutes into the film, is probably my scene of the year, and it’s largely thanks to the intricate interplay between Macfadyen and Julia Garner. Garner’s character, Jane, is a worn-down assistant to a movie exec, and throughout a working day, she begins to suspect that her boss is sexually abusing women behind closed doors. She visits Macfadyen’s character to report this abuse, but in just ten minutes, he convinces her that speaking out is the last thing she wants to do.”

“Macfayden appears warm and welcoming at first, smiling and laughing casually, almost goofily, so that Jane feels she’s in a safe space to open up. His face is open, concerned, empathetic, his gaze fixed on her so she feels she has his undivided attention. As Jane begins to describe ‘a girl who arrived today, she’s very pretty, and she’s young’, Macfadyen’s eyes widen and eyebrows shoot up on the words ‘pretty’ and ‘young’ — you see him taking note of these details so he can use them against her later and paint Jane as jealous. His forehead creases, and then he pauses for a skeptical ‘…and?’ At this point, his body language begins to subtly imply that Jane is wasting his time: he nods rapidly and talks over her as if hurrying her along, scrawls notes on his notepad, and rubs his eye as if he’s tired and wants this over with. Macfadyen gently and impatiently taps his fingers against the desk.”

It’s not just Macfayden and the equally excellent Garner (whose performance we wrote about here) that make this scene so memorable; Green uses costumes and sound to make Macfadyen’s manipulation feel so menacing. When Jane enters the room, she’s wearing a baggy coat and a long, woollen scarf, almost like armour to protect her during this emotionally vulnerable confession (we wrote about the film’s costumes here). Casually, Macfadyen’s character asks Jane if she’d like to take her coat off — an innocent enough suggestion, although the more he insists, despite her polite “No,” the more it feels like a demand. Jane compromises by taking off her scarf and keeping her coat on; “much better,” Macfadyen smiles. Already, he and Jane are engaged in a subtle power play.

I could talk about the genius of this scene all day, but there’s one last moment I’d like to highlight: the simple act of Macfayden passing Jane a box of tissues when she starts to cry. Green manages to make even this feel like a violent gesture. It’s not a soft, cardboard box, but a grey, metal one, menacing even as the tissues inside are meant to offer comfort. Sound designer Leslie Shatz underscores the coldness behind Macfadyen’s gesture by making the sound of the tissue box crossing the desk loud and screeching, like nails on a chalkboard. Orla Smith

Read our full essay on Matthew Macfadyen’s performance in The Assistant.

“I taste London in this cake!”, First Cow

The third time we see Cookie and King-Lu bringing their oily cakes to market, there’s already a queue awaiting them when they set up in the morning. The Chief Factor’s (Toby Jones) right-hand man, Lloyd (Ewen Bremner), walks straight to the front of the queue and commands, “Hold one out today. The Chief Factor wants one. He’ll be here soon.”

At this point of the film, there has been talk of the Chief Factor and his extravagance in bringing the “first cow” to Oregon to provide milk in his tea. But the first time he appears in the film is after this fanfare, so that our curiosity is especially piqued. A shot of Cookie’s hands adding the pastries into a pot full of oil stands in for the passage of time, and we cut to a man dozing off while standing guard. His shoulder is tapped by a walking stick that is then revealed to be carried by the Chief Factor, who commands, “Look alive, son, ” before jumping the queue to get a cake. It’s a surprise to see the diminutive Toby Jones in this role, holding such power, and so unwilling to allow any slack among those in his employ. His admonishment of the guard is impersonal and condescending.

“I’ve heard about your cakes. I’d like to try one if I may,” the Chief Factor says. “How much?” “For you,” King-Lu replies, “only ten silver pieces.” In three sequential shots, Reichardt lingers on the transaction of coins for goods. First, we see the Chief Factor counting his coins as he looks down on Cookie, only his hat visible in the frame. Cookie is on the ground cooking, putting him at a lower level than the Chief Factor, and reinforcing the Chief Factor’s power here, even as he’s played by the not very tall Toby Jones in a top hat. The Chief Factor hands Cookie his coins; cut to Cookie passing the coins to King-Lu, cut to King-Lu pocketing the money in their bag of cash. Reichardt’s cuts draw attention to the chain of goods exchanged, as a reminder that the Chief Factor is now paying Cookie and King-Lu for goods made with his cow’s milk, which they stole. He doesn’t know this, at the time, of course, but he gladly hands over his cash, and they happily take it.

Although King-Lu is holding a basket of pre-made oily cakes, Cookie takes a fresh cake hot out of the pot for the Chief Factor. As the camera pans down to show Cookie adding the final touches to his masterpiece, the Chief Factor’s arm and then hand remains in the bottom right of the frame, his power and presence still felt. The Chief Factor looks down at Cookie’s work with great interest, before Reichardt cuts back to Cookie, as he adds a coating of honey to the cake and then some cinnamon. “A little cinnamon is nice,” Cookie explains, his voice wavering with a hint of nervousness as he feels the Chief Factor’s eyes boring into him.

“I taste London in this cake,” marvels the Chief Factor on the first bite, savouring it with a twinkle in his eye. He looks at the cake like it’s the best thing he’s ever seen, reminiscing about South Kensington back home. King-Lu looks slightly apprehensive, while Cookie beams with pride. The Chief Factor takes no notice, too busy savouring every bite, tenderly pulling small pieces off the cake and bringing them slowly to his mouth. The irony here is that the Chief Factor is only able to enjoy these oily cakes because Cookie and King-Lu stole the milk from his cow. Although he has not yet realised this, it sets up Cookie’s and King-Lu’s crime as minor and truly victimless because the man they have stolen from is pleased with the result. In fact, he’s adamant that Cookie and King-Lu understand just how much he appreciates their product: “ I commend you, sir… on this delicious… baked comestible.” He pauses after ‘sir’ and ‘delicious’, choosing his words carefully.

“I hope you won’t be leaving too soon,” adds the Chief Factor. King-Lu cautiously replies, “We have no plans,” trying to keep his cool but looking slightly uncomfortable as he continues to do trade, accepting cash from someone offscreen. “Very, very good,” says the Chief Factor with a smile, before leaving the frame utterly satisfied. Once the Chief Factor departs, Cookie and King-Lu exchange a look. Cookie is smiling and pleased, as if the Chief Factor’s approval has persuaded them they’ve done the right thing by selling oily cakes made from the Chief Factor’s stolen milk. King-Lu attempts to smile back at him, but it’s a fake smile. When he stops looking at Cookie, his expression is less enthused and more pensive, as though he’s relieved they got away with it this time, but isn’t sure that they’ll continue to do so. Alex Heeney

This is one First Cow scene analysis of three. The other three were published in our ebook Roads to nowhere: Kelly Reichardt’s broken American dreams, alongside analyses of scenes from Reichardt’s whole filmography. Check out the ebook here.

The boxing ring rap battle, The Forty-Year-Old Version

In my favourite scene from The Forty-Year-Old Version, Radha (writer-director-star Radha Blank) attends a Queen of the Ring rap battle where four women eviscerate each other with words. At this point in the film, Radha isn’t feeling great about herself. After one disastrous performance at a showcase, she has decided that her foray into rap was a “lapse in judgement” and that the safe bet is to keep working on her play, which old white gatekeepers have sanitized beyond recognition. Radha is at the point where she needs to decide how much she is willing to sacrifice for artistic opportunities. What’s the point of having a play on Broadway if she isn’t even proud of it?

While this question hangs in the air, the energized camera moves around, capturing each performer in action as the battle commences. Occasionally, there is a cut back to Radha, who reacts along with the crowd. There’s no question that she loves every moment of what she is witnessing, sometimes letting out a silent whistle or exchanging looks of appreciation with D (Oswin Benjamin). Unlike Radha, these women aren’t sanitizing shit. They say what they feel, even if it’s deeply insulting. No old white man is stepping in and telling them their art is “a little inauthentic.” Watching these female rappers express themselves without restrictions has sparked something in Radha that can’t be easily extinguished. In this scene, a future sans “poverty porn” finally comes into focus. Lindsay Pugh

Read our review of The Forty-Year-Old Version.

Talking over the intercom, Proxima

Alice Winocour’s incredibly moving film Proxima comes to an emotional peak toward the end of its runtime, when astronaut Sarah (Eva Green) is reunited with her daughter, Stella (Zélie Boulant), but the two are separated by a pane of glass. Sarah is about to depart for a year to space, so she’s in quarantine, but she’s allowed to see Stella one last time before she leaves.

This scene is so heartbreaking, especially as we’re living through a pandemic, because of how it explores the difficulty of intimacy when you’re not in the same room as your loved one. Sarah and Stella both have a microphone on each side of the glass that they can speak into, but it’s plugged in far away from the glass. If they want to be able to hear each other, they have to be far away from each other; if they want to be close, they won’t be able to hear each other. Eventually, they decide that physical closeness is more important than words, and the two come right up to the glass divider, placing their hands on top of each other. At one point, the reflection of Stella’s face even overlaps with Sarah’s (as pictured in the above image), a beautiful visual representation of their connection in that moment.

When we talked to sound editor Valérie Deloof about crafting this scene, she told us, “For the quarantine scene, the sound was actually played over loudspeakers and recorded on either side of the glass; we therefore had the choice between a close sound recording, a normal pole, and a diffused sound, which made it possible to choose the best possible balance to make the separation between Sarah and Stella felt. [Dialogue Editor] Laure- Anne [Darras] and Alice [Winocour] spent a lot of time on this because this balance was fragile. The sound behind the glass was too muffled to be intelligible, and the changes of the camera axis and the space created sound breaks that were too violent, which could break the intimacy of the scene. The balance was found when we started to cry with each screening.” OS

Read our interview with sound editor Valérie Deloof.

Mika’s boat dive, Sibyl

When I’m sick of my job and ready to quit in a fit of rage, I always think about the scene in Sibyl where Sandra Hüller’s Mika dives into the ocean. After watching her film production steadily fall apart as drama between the lead actors intensifies, Mika’s ability to hold it together disintegrates. She can’t communicate with her actors, the film crew doesn’t respect her, and the desire to scream at everyone has turned into a pressing need. Mika is a woman who has been pushed to her limits and no longer has the energy to problem solve. Her reserves have been exhausted.

When Margot (Adèle Exarchopoulos) starts laughing during what seems like the hundredth take, Mika throws up her hands in exasperation, rips off her sunglasses, and screams, “I’m not going to take this anymore.” She’s been a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown since her first scene, and now her feelings are finally coming to a head. After a brief exchange with her PA, she takes off her shirt and unceremoniously dives into the water. While gasping for breaths, she chokes out, “Finish the film without me. They can’t stand me anymore, and the feeling’s mutual.” The scene is a cathartic release for anyone who has suppressed their rage for far too long and arrived at a tipping point. Even after revisiting it countless times, it never fails to make me laugh. LP

Listen to our podcast episode on Justine Triet’s Sibyl and In Bed with Victoria.

The hiking date, Spinster

Spinster is one of my favourite films of 2020, mainly thanks to the penultimate scene. After watching Gaby (Chelsea Peretti) struggle for the better part of a year to figure out what kind of life she wants, everything finally starts coming together. She’s built a healthy relationship with her niece, Adele (Nadia Tonen), adopted a sweet dog named Trudy, and is about to open a restaurant. Gaby initially thought that she needed a romantic relationship for fulfillment but has come to realize that the life she’s built for herself is equally satisfying.

A cliche sentiment often thrown at single people is some version of “love comes when you’re not looking.” If this were a standard romantic comedy, Gaby’s hiking meet-cute would have certainly resulted in a relationship (or at least, the hope of one). Audiences are conditioned to believe that happy endings and love are synonymous, that one can’t exist without the other. Instead of following the expected route, the film doubles down and shows Gaby kindly rejecting a promising but inconvenient romantic prospect.

What I appreciate most about the scene is the easy, natural rapport between Gaby and Will (Jonathan Watton), the lost hiker that she rescues. They share the same humour and take a legitimate interest in each other, two important ingredients for relationship success. When Gaby explains to Will that he didn’t misread the situation but that she’s not interested in pursuing anything further, he respects her wishes and doesn’t try to pressure her into changing her mind. It’s not often that we get to see a character meet “the perfect man” and choose to walk away. Gaby proves that despite what the asshole at her friend’s dinner party said, she really is “single by choice” and finally ready to celebrate without shame. LP

Read our interview with director Andrea Dorfman.

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch great films at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.

Click here to subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter.