Olivia Vinall on bringing Shakespeare’s women into the 21st century, working on TV, and her new film, A Beautiful Curse.

A Beautiful Curse is currently screening virtually across the US until November 22. Click here for tickets.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

When I saw the 2013 NTLive of Nicholas Hytner’s Othello, I had two key takeaways: Rory Kinnear was an Iago for the ages, and Olivia Vinall, as Desdemona, might just be the most exciting young actress to break into the Shakespeare scene. A lesser actress could easily get overshadowed in a production starring Adrian Lester and Rory Kinnear, especially in one of Shakespeare’s Young Women parts that are regularly sidelined by productions. But Vinall’s Desdemona was none of the things you might expect of the young woman who rashly married a Black older man, only to be brought down by a handkerchief: she was self-possessed, self-confident, and most importantly, thoroughly modern.

Vinall has since built a career on playing women who could be marginalized or even feel dated, and making them not only one of the most compelling people in the room, but feel like someone you could meet today. Her Cordelia in Sam Mendes’s King Lear (2014) is the best rendition of the part I’ve ever seen: a woman who refused to be cowed to her father’s will, entirely capable of running a country, and yet full of compassion. She doesn’t feel like a relic of the past who feels filial responsibility; she feels like, as Vinall envisioned her, a modern day law student who could have been my classmate.

Modernizing and shedding new light on classical characters is no easy feat, and part of that is because the authors themselves often didn’t care enough about the characters to make them meaty. There’s a reason that actors like Cush Jumbo, Maxine Peake, and Ruth Negga are playing Hamlet, that Harriet Walter played Henry IV and Brutus, and Adjoa Andoh played Richard II. As written, they’re better parts. As Vinall put it, what differentiates Shakespeare’s roles for men and roles for women is that “Iago gets to say, ‘I’m going to do this. Watch me do it.’ And then he does it. And you’re like, wow, how amazing. Instead of after the event being like, ‘Oh, I’ve been affected in this way.’” Vinall’s performances push against the sidelining of these women. I was constantly wondering what Vinall’s Desdemona and Cordelia would do next, because one thing was for sure: they could go head to head with any of these men.

Although Vinall would likely jump at the chance to take on any of the male roles in Shakespeare, transforming his women into compelling and relatable characters is an equally valuable — and likely harder — project. Having cut her teeth as Juliet in Romeo and Juliet, Vinall recalled, “I really rebelled against the idea of ever playing Juliet. When I was young, I was like, I don’t want to play her. What a drip. I want to play the men. She’s so boring. What is this love stuff?” But just like she did as Desdemona and Cordelia, she found a way into Juliet that made her a character worth caring about, despite not being one of the men.

After proving herself through her work with the Bard, Vinall has continued to do exciting work in theatre, taking on parts that are either rarely written for women or performed with much consideration. In 2015, Vinall originated the role of Hillary in Tom Stoppard’s The Hard Problem (also directed by Nick Hytner and recorded for NTLive), in which she is equally convincing as a super smart science graduate student as she was as Shakespeare’s women. Her knack for the rhythms of language was also on display here. In 2016, she starred in all three of the National Theatre’s Young Chekhov plays (Platonov, Ivanov, and The Seagull), all often performed in one day, in which she played three different versions of Chekhov’s ideas about women. By casting Vinall in all three roles and putting the plays back to back, Jonathan Kent’s productions really spotlight the women and their changing roles in Chekhov’s early plays. A recording of The Seagull is now available to libraries worldwide in The National Theatre Collection II.

While theatre has offered Vinall more opportunities to really sink her teeth into meaty material, she’s also been quietly working on TV and film throughout much of her career. Two of her most noteworthy TV performances were in the miniseries The Woman in White, adapted from the Wilkie Collins novel, and the BBC’s limited series Roadkill (written by David Hare who also penned the translations of the Young Chekhov plays). In The Woman in White, Vinall plays two characters who, by virtue of being strikingly similar in appearance as written, seem somehow spiritually connected. She is both Laura, a well-to-do woman confined by the societal expectations of marrying for status, and Anne Catherick, a poor and possibly insane working class woman. In Roadkill, Vinall stars as Julia Blythe, assistant to the Prime Minister (played by Helen McRory). Julia is orchestrating many things behind the scenes while being constantly underestimated as a young woman.

When Vinall and I sat down in March to talk about her career, it was on the occasion of the world premiere of her new film, A Beautiful Curse, at Cinequest, where it won the New Visions Feature Film Competition. Vinall plays Stella, a woman afflicted with a mysterious sleeping ailment on a deserted island in Denmark where a silent pandemic is putting people permanently to sleep. In the film’s first half, she is only seen as the figment of Samuel’s (Mark Strepan) imagination; he stumbles upon her sleeping in her apartment when looking for a safe place to sleep, and begins to believe himself in love. What could have been a Manic Pixie Dream Girl role is elevated both by Vinall’s performance and the film’s gear shift in the second half when Samuel is suddenly afflicted with sleep and Stella is awake, allowing us to meet her on her terms — at least to a degree.

In this wide-ranging career-spanning conversation, Vinall discusses playing Shakespeare, working with great texts on stage, learning from great actors like Simon Russell Beale and Adrian Lester, and why recording audiobooks is more than just a way to make end’s meet. Her audiobook reading of Far From the Madding Crowd was released in summer 2020, and her ability to bring multiple characters to life with different voices and accents make it one of the best audiobooks I’ve listened to. We spoke in March, just a few weeks before her Roadkill co-star McRory had passed away, which is why the tone of our conversation about her is mostly awe rather than also sadness.

Seventh Row (7R): What got you interested in acting and wanting to pursue it professionally?

Olivia Vinall: It’s a question that I’ve asked myself so often. Most people have that moment where they go, “I was young, and I was on stage, and I realized I wanted to do it.” But it took longer for me to realize that the thing I always went back to, even from a young age, was acting. I moved around a lot as a kid, and at each new school, I’d go and join the drama club, no matter what.

I’ve always been so interested in seeing what it’s like to live in other people’s shoes. As is probably common with a lot of actors, when you feel quite shy as a kid, and you can have that release, somehow, it’s really appealing and attractive.

It was a slow buildup for me to realise. I remember, one day, speaking to my mom, and I didn’t know what to do for university or where to study. She said, “What do you love more than anything?” She knew the answer. I knew the answer. I finally said it out loud, and she’s like, “You’ve got to follow your dreams. You just have to do it. Life is too short. If you’re lucky enough to be able to, then just go for it.” I kind of cracked on from there.

7R: I know that you trained at the Drama Studio London. What do you feel you got from that training?

Olivia Vinall: The course I was on was just a one-year post-grad. I had done three years of drama at university. Before university, I was living in Belgium. I didn’t really know about drama schools. I’d heard about RADA, but I just didn’t feel ready. I felt too young. So I studied drama at uni and then couldn’t afford to do another three years.

7R: Like most people.

Olivia Vinall: Exactly. It’s crazy, isn’t it? I wanted to go to those places, but also I just found this course, [at the Drama Studio] and it was a really lovely school. It kickstarted you straight into the industry. It taught you all about agents and things that I had no idea about, and equity and stuff like that. It was a lovely year, but it’s pretty intense trying to cram it all into one year.

7R: Did you find that you got good technical training from drama school? Or was it more about getting into the industry?

Olivia Vinall: At the time, they didn’t really have the resources to do much TV kind of training. I know that it’s gotten much more [focused on TV] now since I’ve left. But we only had a couple of classes. It was [about], like, how to hit a mark on the floor, being in front of a camera, hearing what happens before action, and stuff like that.

We did a lot of vocal work, which really helped me for theatre work. Especially because Othello and Desdemona was my first big, main theatre role. And the Olivier, which it was [performed] in, is 1,500 seats approximately. You had to really pump it out there. So all those classes really, really helped me.

7R: What was that like, to be thrown in at the deep end with Othello at the National Theatre? The Olivier is an amazing theatre, but it’s huge.

Olivia Vinall: I’d seen shows there since I was a kid. I remember so clearly, I had three rounds of auditions for Othello. The first one was in a tiny room with the casting director, which was like ten minutes. The second one was with the director, Nick Hytner, and it lasted about two minutes. We read a scene, and then I had to leave. And I was like, “He hates me. This is terrible.”

Then, I got a call to do the third round. They basically just led me through the corridors of the backstage at the National, and they’re like, “Oh, we’re just gonna do a scene on the stage.” I was like, “What?!” I was so unprepared. They took me through a little side door, and suddenly, it was the huge stage and the empty auditorium. The director, Nick, and the vocal coach, Janette Nelson, were standing in the stalls to see if I could fill this space. It was insane. Adrian Lester, who played Othello, was there.

They’re like, “Let’s just do the handkerchief scene.” They just picked the scene. And I was like, “Okay, Let’s do this.” It was a few days before Christmas [in 2012] when the world was supposed to end. And I thought, this is either going to go terribly, or I’m not going to know that it went terribly because everything will have stopped.

7R: I’ve heard that actors give other actors tips about where you have to stand on the stage in order to hit the back of the back of the theatre.

Olivia Vinall: They have this famous… Michael Bryant, who is a wonderful actor, they call it the sweet spot. It’s right in the middle. And they’re like, when you stand there, you feel like you can fill the whole space. Nick did a really clever thing in that production with all the little boxes of scenes that came out [i.e., smaller sets that would help to confine the large space of the Olivier stage]. That really helped with the sound but also creating the eyeline, making it really intimate so you didn’t feel too lost on that stage.

When we did King Lear, and I came on as Cordelia when she’s the Queen of France, Sam Mendes, our director, opened the whole stage up, and I had to stand there with this gun on this empty stage! I’ve done five shows on that stage now. It weirdly feels really homey on that stage, if that doesn’t sound too silly. I get so excited by it. I love discovering the sounds and the different spots and how they work.

7R: How did the set in Othello help you with the sound?

Olivia Vinall: I think because he had all these boxes that thrust out, and we do the scenes within them, it kind of contained the sound so it reverberated better in there. And also, I think it helped the audience’s ear connect [the visuals with] how they heard it. It just really focused you in. Because you can get a bit lost sometimes on that stage.

7R: Do you have a general approach for how you go about finding a character? Is it about just thinking about the dialogue first or the physicality? Or does it come when you collaborate with other actors or get the costumes?

Olivia Vinall: It’s such a good question, and it’s one that I’m constantly trying to reevaluate for each project. I think coming from theatre, the first thing are the words, for me, and then that’s the key into creating a whole background in that Stanislavskian approach of their whole world beyond words.

It was wonderful for Othello, because of imagining it in a contemporary setting, I was thinking, “Why would Desdemona make these arguments about Cassio?” I was able to see her as someone at university age, and her father had all these expectations from her. Maybe she was going to go to Cambridge and study law. Her arguments are so good that I thought, what would create that in someone? What would be her passion? I thought she was probably a law student so she could put Cassio’s suit forward really well. I love creating that backstory.

I’m getting more and more interested in, I want to say, method style, but I don’t mean where you’re so fully in it, and you don’t speak to anyone. I don’t mean like that. But I think immersing yourself as much as possible helps me, personally.

I did three Chekhov plays, as well, on the Olivier. When I did The Seagull, [scenes] like when she comes back in from the rain, I just wanted to come on stage drenched. They were like, “You’re gonna get pneumonia each night! Don’t get in the shower with your clothes on!” But I had to do it. I’m sure a more accomplished actor could just imagine those things fully, but I need little anchors that get me there. It’s quite a physical thing.

I love working with other actors; they bring so much. It’s what choices they make, as well, for their characters, that really informs me.

7R: I feel like you’ve worked with so many of my favourite actors.

Olivia Vinall: Oh yes! Who are your favourite actors?

7R: Oh my gosh. I’m a big fan of Rory Kinnear, Adrian Lester, who were in Othello, and Simon Russell Beale and Kate Fleetwood who were in King Lear. And you worked with Helen McCrory more recently in the TV series Roadkill. If I were to look at everybody you’ve collaborated with, it’s like, oh my god, that sounds like a dream.

Olivia Vinall: I pinched myself. I’m like how [do I get to work with all of] these people who I’ve always admired. What’s been so lovely to find out is how nice they are, how lovely and how giving and generous they are. They’ve all helped me so much to understand and build up a process. They’re really open and lovely. That’s cool that you like them, because they’re great people.

7R: What do you find that you’ve learned from working with all these other actors? You mentioned that they helped you build up a process.

Olivia Vinall: I will never forget how generous Adrian was with me. Before we started Othello, he gave me time. I felt really insecure because I was such a newbie, and I kind of felt like I didn’t deserve a place there. He was like, “You have to just believe you’re here, and you’ve been given this for a reason.”

Even recently with Helen McCrory on Roadkill, I remember our first scene together. I’d seen Helen and Hugh Laurie, who was in it, in so much growing up, I was so nervous. I remember I had to carry a cup of tea over to her as her assistant, and my hand was shaking so much. They had to glue the cup to the saucer.

She just just put me at ease, and we had a lot of laughs. That just made it feel really comfortable. Watching her work, she brings something new in every we take, so you’re kept on your toes. It’s kind of improvising, but it’s around the script. David Hare had written it, who I’d worked with before, so it felt really comfortable and collaborative.

I also really learned from all of them how to just be generous and not be all ego; just support every level of person on set and know that everyone has a specific job that’s important. Sometimes, people can get very much in their own head, in their own worlds. So it’s staying open to everyone else.

7R: When I think about a lot of the roles that you’ve played, especially in classic texts, I feel like you imbue these women with really modern sensibilities. I’d never seen a Desdemona played like that, or a Cordelia that felt like a person who I could know, today, who’s a real person with agency. You get to do the same thing with the miniseries The Woman in White, which is a period piece, but it’s got a very modern bent. Is that something that’s important to you when you’re accepting roles?

Olivia Vinall: I can’t tell you how wonderful that is to hear because that is at the forefront of what’s important to me. In the past, or growing up, I felt like, “Why are we seeing this again? What else could you bring to this play?” Often, I’ve watched productions and thought they’ve really pushed the women to the side. They’re just a device. They’re being killed by the men. They’re being abused. It’s like, who are they? What is their reality in this world?

I don’t want to be a device. So if I can ground them in a contemporary truth that feels real to me, then I can try and understand why someone would do that now. To me, that’s why I’d want to see a show [restaged] today. I want to go to Shakespeare now to understand how it reflects on my life.

With Desdemona, I struggled for a while thinking, why would she sacrifice this for this man? Why would she believe them to the end? That purity of her love was something that I discovered as we worked on the play. In a similar but very different way with Cordelia, who is she? Who does she need to be in front of her father and with these siblings? It was very much her wanting to be a woman in the world and have that presence and say no, for the first time, which can often be so so hard, and just assert her right to be independent, but still loving.

With The Woman in White, I was like, I just can’t bear it if this is a period drama where Laura is abused, and that’s it. I explored a lot about synesthesia, her sensory understanding of the world, and how valid that is; how that can be overlooked and undermined often. Sensitivity is a strength, I think, not a weakness. That was great to explore with these amazing female characters.

7R: I totally know what you mean about female characters getting sidelined in Shakespeare productions. It’s often like, did the director forget that they’re there? Were there rehearsals with them? Because it seems like they forgot to do that.

Olivia Vinall: Yes, totally. Absolutely. At the beginning of Othello, [Nick Hytner] was like, okay, Desdemona, Iago, Emilia, Othello: that is the tragedy of the play. It’s not just these two men. Desdemona dies. Amelia is abused and manipulated. How can we sideline them? And I was like, “Yes! Why has this been overlooked?”

7R: I wonder about what that’s like for you to play, as an actor. When I interviewed Maxine Peake about playing Hamlet a few years back, she said that the challenge of playing Ophelia is that your big moments all happen off stage. And that’s a problem with a lot of female characters in Shakespeare. You have to play the after effects on stage, but you don’t actually get to play any of the big moments. Does that resonate with you? Because you’ve played so many women in Shakespeare.

Olivia Vinall: Absolutely. It’s really frustrating. So often the men get to have that emotional journey in front of the audience, and they get those wonderful monologues and soliloquies where they argue with the audience. Iago gets to say, “I’m going to do this. Watch me do it.” And then he does it. And you’re like, wow, how amazing. Instead of after the event being like, “Oh, I’ve been affected in this way.”

I’ve always really admired people who play Ophelia. I think that is a really hard part because it happens offstage, and she has such a big change when she comes back. It’s hard to believe in it, isn’t it? I just want them to be on stage explaining themselves more.

7R: How do you deal with that when you don’t get to have those big monologues? What is your approach, then?

Olivia Vinall: I think there can be the danger of wanting to explain it all. When you come back in, I’ve definitely panicked, and thought, “How can I express every emotion that I’ve been through in the interim?” But actually, I think [you have to trust] that an audience is so much more intelligent [and can understand] that that [character’s off-stage] experience has happened. You don’t need to explain it all when you come back in. That’s something I’ve tried to work on.

7R: One of your early roles in 2010 was playing Juliet in Romeo and Juliet in Mussolini’s Italy, which was staged in a small space at the Leicester Square Basement Theatre. What was that like? How did you approach Juliet?

Olivia Vinall: I was at drama school at the time. Linnie Reedman, the director, came into our drama school and said that someone had dropped out, and could they audition me? My principal let me leave school early for, like, two months to do this show. It was a really tiny space that had one exit, and on the other side, we had to build a fake exit. So we’d all pile in on stage left, pretending we’d left the stage.

I have to say, I really rebelled against the idea of ever playing Juliet. When I was young, I was like, I don’t want to play her. What a drip. I want to play the men. She’s so boring. What is this love stuff?

You think you know it, and then you read it. It’s the most beautiful language I’ve ever read, I still think, to this day. It’s the most beautiful exploration of feelings. I feel really lucky to have ever got to say them out loud.

I haven’t seen it since, but I’m really excited to see the Jessie Buckley and Josh [O’Connor] version. Baz [Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet] is one of my favourite films ever. I love it so much. When you watch it, when you discover it when you’re younger, you feel like you’ve been given a key. You’re like, “I get it now!”

7R: I feel like it perfectly understands the play, which is amazing, because the line readings are terrible.

Olivia Vinall: And I quite liked just throwing that to the wind, like, whatever.

7R: At the National, especially, because it’s in rep, you’re playing these parts over a long period of time. How do you find that your performance shifts or changes over the course of a run?

Olivia Vinall: I always feel like, on the last night, I want to go back and give people their money back for the first weeks. It’s so insane that you open the show, get reviewed after a week, and then have, like, an eight-month run. I know you should be completely ready at that point. But you learn so much doing it night after night.

Simon Russell Beale always had this phrase about holding it to the light, and then it takes on different meanings because of the way that the light captures it each night. And it does. It changes. It’s like this strange beast that takes over in different ways [depending on] what everyone on stage is bringing each night, what energy they have.

We did the Young Chekhov rep season there. Twice a week, we did three shows in a day. It was insane. It was like twelve hours of a show with, like, forty-five minutes in between.

7R: I did not realize those were all done in one day.

Olivia Vinall: Yeah, it was epic. It’s probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But just the most amazing. You’d start with his first play, Platonov, and then go to Ivanov, and then The Seagull: his first three. So you see how his writing develops over those years. And also how the three women that I play, and how he depicted different women, changed in writing over those years. And then also, your energy changes. You’d end on The Seagull, so I’d technically be having to get younger through the day, but also in pain by the end.

Sustaining yourself for a long run is tricky. You have to keep on top of keeping your voice safe and really basic practical stuff. You’re, of course, relieved, in a way, on the last night. You’re like, “Wow, we’ve done this.” But the next day, I always wake up hearing a line thinking, “I should have said it like that.” Always regretting!

With the Chekhov, we had five months’ break because we started them in Chichester, and then moved to The National. It was so wonderful to revisit the part because of that feeling when you end and you want to go back in and get stuck in again and be like, “Actually, maybe, how about it means this?” We had the chance to do it! That felt really, really lucky.

They were full on energy-wise, and I just loved each of those women. Again, it was trying to bring something to each of them that doesn’t just mean that they’re a device for the men. I think The Seagull is just one of the most incredible plays written.

7R: I love it, too. I went into the archives and saw the production with Kristin Scott Thomas as Arkadina, which was amazing,

Olivia Vinall: Was that the Carey Mulligan [as Nina] one?

7R: Yes!

Olivia Vinall: Oh, wow. I’d love to see that. David Hare did that version, and then he did our one, as well.

7R: Nina seems like a really tough role to play, because I could see her, in the wrong hands, not being an interesting, thoughtful character and more of a histrionic victim.

Olivia Vinall: Yeah, absolutely. I feel like I often come across parts that fall under that label. I really rage against that. I go, “Okay, right. Let’s start from the beginning. Who are they?”

Nina was a huge challenge because, again, so much of her change happens offstage. You hear about her experience, then you see her. Her joy and passion and excitement for life is just crushed and taken away in a blip.

I saw her as in love with Arkadina. I thought she just wanted her life. The most exciting thing around, so much more than Trigorin, was watching Arkadina and [wondering], who’s close to her? How can I be her? What moths are also drawn to that flame? That, to me, was the motivation.

At the end, she says, “It mustn’t be for fame. It mustn’t be for glory. It’s about the ability to endure.” I think about it all the time. It’s just, for me, an important reminder, as an actor, not to be swept up in that side of things, to just keep going with what you believe in. And hopefully, you won’t end up with the same fate as her.

7R: Because Chekhov in English is a translation, it can be modernized a lot more than when you’re doing Shakespeare. What were the differences, for you, between doing these great classic texts translated from a foreign language into English versus in the original English.

Olivia Vinall: The versions [of Chekhov] that we did, David Hare didn’t make it too modern. He wasn’t creating a language that feels colloquial to now. But I know there are productions that often do that. I haven’t seen any, but I’d be quite interested to see how they adapt Chekhov in that way. Have you seen any? I don’t know if it helps make it feel more relevant.

7R: I haven’t seen it with Chekhov. I’ve seen the Schaubühne productions of Shakespeare translated into German. I’d never seen anything like that before. They have subtitles that are in English, which are just Shakespeare’s original text, but then they ad lib on top of it, and they start talking to the audience. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen. You could not do that on the English stage.

Olivia Vinall: No, it’s very sacred, isn’t it? Every word must be said this way. The language, of course, is wonderful and to be adhered to, but I do admire people who find freedom with it. We were talking about the Baz Luhrmann version, and even just messing up whatever version or rhythm there is, I’m interested in, because it might bring a different heartbeat to it.

7R: I’m less familiar with Platonov and Ivanov so I don’t know the characters as well, but maybe you can tell me a bit about the work on those two productions, too.

Olivia Vinall: Platonov is his first work. It was unfinished. If you did it unabridged, it would be like eight hours. We cut that down to about four. It’s this epic, sprawling piece about the main character, Platonov, who is a bit of a lothario who falls in love with these different women. He feeds off them a little bit. Sofya, in that one, leaves her husband and gives her life to this man. And then, he just casts her aside. It’s interesting seeing that formative writing of his, how it develops into the other characters.

And then Sasha, in Ivanov, falls in love with Ivanov, who’s also married to a very sick woman. So he develops each play. I saw her as someone who has read Ayn Rand, and wants to be independent, and sees a thinker, and they fall in love with each other’s minds. They can talk to each other really well. He’s the only man who has been around for her to have those discourses with. Each one — Sofya, then Sasha, then Nina — informs the other. I felt like one giant snowball, by the end of the evening, of all these women.

7R: That’s so interesting. I hadn’t realized that they all have a similar arc. Do you think of them almost as the same character developing? Or do you think about playing them as completely different, like with totally different physicalities and talking differently?

Olivia Vinall: By the end, I found them to be myriads of one energy. But each one, I explored a different kind of rhythm and perspective. It felt like Chekhov exploring who women are; tussling with that and not really getting to understand it, but having these different facets and different versions of a form that he was exploring.

I think he writes women really well. He’s written these really incredible characters. It was almost like being able to play one character, but all of their facets.

7R: I think with The Seagull, it’s like, “Who are the men? Who cares!”

Olivia Vinall: Yeah, exactly. Exactly. Oh my gosh.

7R: We talked a bit about the characters, but maybe less about the experience of working with this particular cast and director. I imagine working with Sam Mendes is different from working with Nicholas Hytner is different from working with Jonathan Kent. What do those different collaborations bring to you, as an actor.

Olivia Vinall: Nick Hytner had such a clear vision at the beginning. He had the setting. He knew how he wanted it to be. We found freedom playing the characters and having the discussions and doing all of that work beforehand. And similarly with The Hard Problem, which he also directed.

With Sam [Mendes on King Lear], it was also wonderfully free, because on the first day, he sat us down and said, “We shall, by indirection, find direction out.” You know when you’re nervous, and [you’re working with] someone you admire, and they’re going, “I don’t know, either! Let’s find it together.”?

[Sam would] get loads of rugs and put them in a circle, and we’d all sit around it and take our shoes off. And then we’d just try the scene. You’d step into the circle for your scene, and you try it in loads of different ways. You’d be like, “Now, we’re at a party.” That opening scene of Lear is really difficult. Finding a way in is really tricky. We wanted to understand what world we were going to be in.

What’s so great about working with these directors is that they’re so, so intelligent, so they understand the importance of creating a world that we comprehend. And it’s not just archaic and isolating. We played a lot, and it felt very, very free.

Jonathan Kent [who directed the Young Chekhov trilogy] is just this bundle of energy. I don’t know how he does it. All his productions exude life and joy. He put that into his style of directing. To be able to sustain directing three shows, I mean…

The cast was kind of an ensemble, but just [myself] and one other actor did all three shows. You’d rehearse in the day, and then most people would leave, and you’d stay on and then rehearse the next show into the evening. Jonathan never lost his energy. He was just so excited by doing these productions. That kept us going.

It’s interesting how different people work. I definitely would like to work with some more women. I need that.

7R: The Hard Problem has got to be the polar opposite of doing Shakespeare and Chekhov, since you were actually originating a role. And you were in the Dorfman Theatre, which is a tiny little theatre at the National, compared to the Olivier.

Olivia Vinall: I still count my lucky stars that I ever got to play Hillary. I feel like, in years to come, people will come back to that play and see it in a very different way and learn a lot more from it. I think people maybe expected something from Tom Stoppard’s next play. I actually think he’s properly a genius. The discussions he has about goodness, and consciousness, they just blew my mind. To get to see them for the first time, and originate the role, as you said… I’d never done that before. And I haven’t done that since.

She’s just on fire. Hillary is a woman at the top of her game. She knows more than the men. She can kind of achieve anything, but she also has this longing to understand whether her daughter is okay and who she is, and whether you can be good. I thought that was a beautiful weaving of these two ideas of science and heart and head.

Learning about the science, too, was amazing. Working with Nick on Shakespeare, and then doing this, I was like, “Nick. It’s so freeing!” It’s got its own rhythm. [We can] go anywhere with this. It made me realise I should have that approach more with classical texts.

Tom’s writing has a rhythm, and you need to be very precise with it, with the full stops. He really loves the word ‘if’, and if you missed saying the word ‘if’ at the beginning of a sentence, he’d always know. And he’d be like, “Olivia, if! Carry the argument on…”

She was a joy. I think about her a lot. I think about her mind a lot. I know there have been other productions since. I’d love to see one. I think she’s great. I think it’s a great play. I’d do it again in a heartbeat.

7R: Did it change with you? I know with new work, often, things get edited a bit in the rehearsal process, but maybe that’s different if you’re working with Tom Stoppard.

Olivia Vinall: I think so. I think probably, under other circumstances, they would. He was just explaining to us, the whole time, what it was about. I’m so embarrassed, the very first time we met, and we sat around to read the play, he went, “Any questions?” I had so many questions, but I put my hand up, and all I could say was, “So… molecules…” And I froze. It was so much to start to understand. And he looked at me like, okay, it’s a long journey. He was lovely.

7R: Something that I really like about your characters is I feel like these are really smart women. Not everybody can do that. You feel like these are women who are intelligent and thoughtful. Even if they’re not necessarily speaking a lot — Cordelia doesn’t speak a lot — I still get that vibe.

Olivia Vinall: That is an amazing thing to hear. I feel a little bit humbled by playing these intelligent women because it makes me feel lacking, somehow, in myself. I feel a bit like I’m flying like when I’m speaking as them. With Cordelia, there’s that confidence to stand up in that situation and speak your truth. It’s something that I don’t find as easy. Hillary is able to take these men on head on.

Even Julia in Roadkill, she’s there with the men going, “I’m going to use this tactic. You can’t see it coming, because you think I’m a woman who doesn’t know anything, but actually, I’m going to do you over and take your job.”

It’s really nice that people have given me the opportunity to play those parts, because they feel very, very different to me, how I think, and how I operate in the world. It’s really, really fun.

7R: Do you have to, in your head, be thinking, what is this character thinking, all the time?

Olivia Vinall: I think it comes from the background research that you do, so that, in that moment, you can be ready to think like them, any which way, any moves that they make. You’re with them. You’re feeling it and experiencing it as much as possible. Because I never want my Olivia head to come in and shy away from it or have my insecurities about how much I know, in that particular field.

Research is really key for me. There’s a Houses of Parliament tour that you can do. I got my little headset, and I went around. I went into the House of Commons [as preparation for Roadkill]. It’s just so important to understand it and feel that world.

7R: I wanted to ask about Cordelia. I remember, years before the production, I saw an interview with Sam Mendes where he was like, I don’t know about King Lear: you have to figure out why Cordelia doesn’t just tell Lear that she loves him. How did you solve that problem?

Olivia Vinall: It’s really difficult, isn’t it? I just saw her as someone for whom her love is [expressed] in not saying it. Being demanded to do something — her love is greater than that. Like Juliet says, “My love is as bounteous as the sea.” It transcends words. If he doesn’t understand that, or see that in that moment, then, what is their relationship?

I think it’s so full, so deep, that she can’t speak it. And actually, the simplicity of nothing, that’s taught me a lot in life. You don’t need to hear all the words. You just need to feel it. If the other person is connecting with you, there’s an understanding there that transcends language. That was how I viewed Cordelia in that moment. She has no option but to not be like her sisters, who use all the words and are a bit verbose; [she is] just truthfully her. I really admire that. I think that’s an incredible, powerful quality to have.

7R: What was it like to start making the shift into screen work?

Olivia Vinall: I found it so exciting. I feel like such a novice. I feel like, aaaahhhhh, what am I doing?! I’m really, really enjoying starting to explore it, and also learning from wonderful screen actors, [observing] the ease that they have. It was just a joy, like, working with Jessie Buckley on The Woman in White and seeing her skill and her competence and her ease. People like that are teaching me a lot along the way.

7R: What do you find is the difference for you between acting on screen versus on stage?

Olivia Vinall: You don’t need to worry about projecting out so much to the back of the stalls. That’s something that I’m working on. I can have that tendency to tell, not show, [which is] the opposite of what you should be doing.

I think it’s really wonderful to be able to capture, in one moment, the reality of a situation with another actor. I love being in the real environment for something. That’s so exciting. I love filming outside and having the elements affect your performance, smelling the air. It’s stuff that I try and imagine in my mind in the theatre, but when you’re actually in situ, you get to do it for real. It’s just wonderful.

7R: Does that compensate for the fact that you don’t get to play out a character’s arc in order all together each night?

Olivia Vinall: I do struggle with that. I have heard about films that have shot in order, and I envy that. Because of doing theatre work, you like doing that journey.

It really makes you have to be so on top of that preparation. You start, inevitably, with what you feel is the hardest scene. You’re suddenly thrust [together] with someone whose [character] you’re in a relationship with… and go! You have to already be there. It makes me acutely aware that I have to be ten steps ahead.

7R: I guess you could end up shooting the last scene first. Just like on stage, you learn about the character as you’re shooting it, and then, suddenly, now you’re at the beginning, but you’ve already picked the end.

Olivia Vinall: Yes, absolutely. When you’re on stage, you think about it afterwards, and you go, it’s okay, tomorrow night, I’ll have another go at finding this. Whereas once you’ve shot the scene, and that’s it, I’m very bad at letting go of that and moving on.

When I watch films, I’m just in constant awe at these amazing performances, that emote so truthfully. There are so many amazing actors that I’m like, what an amazing skill.

- Olivia Vinall as Laura in The Woman in White

- Olivia Vinall as Anne Catherick in The Woman in White

7R: In The Woman in White, you play two different characters so you have to track two different journeys and decide how similar you want them to be. I don’t really think they are very physically similar, aside from that they’re both you.

Olivia Vinall: That was a real challenge, because I didn’t want them to be like, “Oh look, Olivia’s just put some teeth in.” Which maybe is the case, and fair enough.

What’s really interesting, in the novel, is how they both have these different sensory experiences of the world. Laura, when she hears music, sees colours and things. The way that Anne Catherick is described, she has all these feelings that manifests in her body from different sounds. When you look at synesthesia, the condition, it’s very, very common in families. There’s a family line link. So I thought, what if that’s the quality that they both have? That was how I started to explore the differences between them as opposed to, hopefully, just visually looking a bit different.

7R: I wanted to ask about Cordelia. I remember, years before the production, I saw an interview with Sam Mendes where he was like, I don’t know about King Lear: you have to figure out why Cordelia doesn’t just tell Lear that she loves him. How did you solve that problem?

Even in the novel, Laura is not given her own diary entries, really. Marian writes so fluently and fluidly about what’s going on, and so does Walter Hartright, but Laura is just, like, snivelling in the corner with a handkerchief in a lot of the book. And I’m like, what is the reality of this woman? She can’t be the centre of this story and not have feelings and her own journey. [Series director] Carl Tibbetts and I spoke a lot about how to bring that out in Laura. And equally, in Anne, [how to] see her pain and her suffering and what she’d been through to get to where she was. I don’t want it to be suffering women for no reason, with no background.

7R: I guess that’s very similar to the Shakespeare problem of you don’t get to tell your own story.

Olivia Vinall: Yes, frustratingly so. I often wonder why I’ve been given those opportunities to play those women. I feel such a responsibility to bring humanity to them. If these are the opportunities I’ve been given, as frustrating as some of those parts could seem, the real joy is going, “Let’s excavate that. Let’s dig away and really understand them.”

I don’t want to watch performances where they’re being sidelined and they’re a device. I’m not interested in work that’s being made like that. I just don’t think that should be done. If that’s the case. I’ll fight tooth and nail for giving them some kind of autonomy.

7R: Can you tell me about Where Hands Touch, where you played a concentration camp inmate, and was one of your first screen roles? I’m a big Amma Asante fan.

Olivia Vinall: I couldn’t believe that she cast me in it. I’ve also admired her work for so long. I remember I had this Zoom casting with her because she was in another country. I was so nervous, just on Zoom, doing this audition. And we had to do the German accents.

I think any story that even touches on concentration camps, you have to be very, very careful about why you’re doing it. Amma is so intelligent. She was someone you could trust with bringing out what was important about showing that story. And Amandla [Stenberg], the lead actress, was just incredible and so young, doing such an amazing performance.

We filmed it on the Isle of Man, and I remember, I was asked a week before to shave my head for it. I was like, okay, yes, let’s do this. It was really freeing, but also very strange walking around the Isle of Man suddenly feeling different in your life, and then filming those scenes.

7R: You were talking about wanting to get into the world of the story. Is that especially helpful when you do period films, because you can really be in that world when filming in a way you can’t on stage?

Olivia Vinall: Yeah, it was really helpful. I did struggle with that with that film, internally, because I felt this strange mixture of depicting this horror, and then you get some comfort [yourself, as an actor]. You get to go to a hotel at night. I struggled with that. I felt like I couldn’t or shouldn’t depict it in some way. The story was important to tell. So that’s what got me through those feelings, but I definitely did find that hard because you want to live a truth of that, but you can never live the reality.

7R: When I hear you talk about how you approach roles, it reminds me a lot of how Simon Russell Beale talks about acting as three-dimensional literary criticism.

Olivia Vinall: He’s so great. I think I’ve probably learned so much of this from him. When he was doing Lear, he was looking into the medical conditions that cause his memory loss. He created such a rich character. He used to do this thing with his hands that was gnarling them in a particular way that was so like my granddad, who had this condition. It was so well perceived, this tiny hand flicker. I thought, it’s those little details that you know yourself, that someone else might not see, that [creates a] full [character].

7R: Were there specific things like that for any of your roles that you might want to talk about?

Olivia Vinall: For The Woman in White, the synesthesia felt like a real, personal thing that I didn’t have to convey overtly, but really helped me as a way in.

In The Seagull, at the end, when she says she’s a seagull, I saw it as a kind of Tourette’s, [to explain] why someone would repeatedly come back to that memory. There’s many different ways of playing it, of course. But for me, it kind of burst out of her, like she couldn’t [control it]. When someone’s been through extreme pain or loss, it can trigger and change something in you. That helped me to understand how that came out.

7R: I know you’ve also done some audiobooks. I’m always very curious if that’s an interesting prospect for an actor or just, like, gotta pay the bills.

Olivia Vinall: What a lifesaver it’s been in lockdown. I converted my wardrobe. I tried to soundproof it and do some [recording] in there.

I’ve always loved listening to them myself. I know, some people don’t. I also really love doing things where people can’t put you in a box of who you should play. I did Far From the Madding Crowd last summer, and there’s like twenty different farmers in there with different accents. You’re playing all these men, as well. I’ve always wanted to play the men. It’s just really freeing. It’s no kind of visual judgment on who you are. That, for me, is the most kind of play. It’s really, really fun. It definitely helps pay the bills, but also I do properly enjoy it.

7R: How do you even prepare to read a ten-hour book?

Olivia Vinall: I tell you, honestly, in the summer, because everyone’s doing it from home, and there’s all these technical difficulties, I recorded a book three times. We got to the last chapter the first time, and the producer said, “You might want to get a gin.” And I said, “Oh, great, because we’re at the end?” [The producer said] “No, because none of it recorded.” It was really hot last summer, and there’s no ventilation in my cupboard. That sounds so boohoo, woe is me. But it was just a practical thing that I never thought of, [the prospect of] it not recording.

7R: I’ve got to ask you about A Beautiful Curse. How did you get involved with the film? The character Stella is sort of somebody’s projection in the first half, and then you get to see who she really is in the second half.

Olivia Vinall: What really appealed to me was — kind of everything we’ve been talking about — that she is the projection of what someone might want from a relationship, Samuel has imagined who Stella is and gone through her stuff. That feels so invasive and awful. The director, Martin [Garde Abildgaard], has so much heart, and he said he was writing the story about soulmates and understanding yourself in a relationship.

And I thought, That’s really interesting, [the question of] what mirror we hold in front of us. What do we want from someone else? And what do we expect them to be? That’s what drew me to the script, originally, because it was another instance of turning what potentially could seem like just a stalker story on its head.

I studied Festen at university, which was done in the dogme style. I’d always wanted to work in that way. That’s what we did on the island. It was all natural light. Everything we found to use was on the island already.

We were talking about the joy of being in the natural environment: being out there in the freezing weather, these sand dunes on this beach. It was something I’d never really experienced before. And they were really up for improvising. I hadn’t had that [experience] filming [before], and that was really cool. The other actor, Mark [Strepan], it was really easy with him. He was very much up for that, too. So it was a very playful time, a very strange time being on an island, and making a movie that’s very dreamlike, as well. I feel like reality and dreams kind of blurred a lot in the filmmaking.

7R: Is there a difference between how you approach when your character is somebody’s fantasy versus when you’re playing a real person?

Olivia Vinall: Stella has so little time in the film to show herself as a real person. I feel like we never actually get to see who Stella really is. And I quite like the mystery of that, that it’s not explained. You’re always wondering, is it Samuel’s perception of her? Is it really her? Is it a reflection of him? Does she even exist?

And that’s why we wanted small changes towards the end. There are tiny subtle differences. I enjoyed that because it leaves it more mysterious. It makes me, when I watch it, reflect on whether Stella is real, or is Samuel searching for who he is as a person?

7R: It’s an intimate film with just these two characters. Talk about the polar opposite of playing in the Olivier Theatre at the National.

Olivia Vinall: It’s the polar opposite. And it’s such a joy to do this. Even calling it a job feels strange, but it’s just great to get to explore the multitude of ways that you can perform and explore human connections. I don’t think I’ll ever be on a tiny island with so few inhabitants again. It was a real isolation experience. Samuel was filming so much while Stella is asleep. I was on this island and would come across the strangest things in the woods — deers and all the snow falling. It was a great time.

7R: What is your relationship with costume? I can imagine this might be different for theatre because you’ve got weeks of rehearsal before you put on a costume in a real way. But I know a lot of actors talk about how they don’t really know who the character is or how they’re going to move until they put on the shoes or they put on the costume, and then everything changes.

Olivia Vinall: I totally agree with that. I feel the same. You’re inhabiting them when you’re inside their clothes. It makes you feel like you’re inside their skin more, in the shoes, especially, because it affects how you walk so much.

I love getting away from myself. I love trying to transform and explore someone else. I definitely feel like I’m a vessel for that. I feel very much that my purpose is to be that vessel, to inhabit these people, and to entertain people in whatever sense that is. I like the escapism of it; it’s appealing to me. I also love changing — I don’t just mean for the sake of it. I don’t mean like I want to change my hair just for me. But I want to forget Olivia as much as possible. All those things help me. Definitely, other actors, who are way more accomplished, could do it without [those changes]. But that is a key for me, to see through different eyes and different body shapes. And also, the restrictions of different costumes. For the Chekhovs, we had to wear corsets for hours.

7R: Oh, my god, it’s like a whole day of corsets.

Olivia Vinall: It was the same for The Woman and White, for the whole filming day. That constricts you and binds you; it bound women at the time. It’s so limiting. Costumes, and the development of clothes, historically, is really useful for that.

In Where Hands Touch, it’s the taking away of identity, making everyone look the same, trying to turn people into animals. It shows how clothes and aesthetics and our looks give people a sense of who they are. That taught me so much, as well, that stripping away of it all.

7R: What do you want to do next? Do you want to keep working in theatre? Do you want to work in film and TV? Do you have your eye on certain roles?

Olivia Vinall: I love theatre so much. That’s where I began and what I’ll always love. But I’m really enjoying filming at the moment, as well. To sustain doing both would be a dream.

In terms of roles, I think it’s great to see Maxine Peake and Cush Jumbo playing Hamlet — all these amazing women tackling these parts. It doesn’t have to be women playing men. They’re just people speaking these words and that experience. I would love to get stuck into other Shakespeare plays in that way.

There’s so many wonderful plays, so many wonderful American plays, as well. I know it’s been done so much, but I love [A] Streetcar [Named Desire]. I could read it forever. I think it’s just amazing. I think one day I’d quite like to direct it. I have a vision of how I’d want to do it one day. That might be fun to try and do.

7R: Are you interested in directing, more generally?

Olivia Vinall: I didn’t really think that I was, but the more people I see doing it, and the more women that I see doing it and also being actors… maybe one day.

7R: Are there roles on your bucket list? Do you feel like you want to do Hamlet, or something like Coriolanius?

Olivia Vinall: It’s really hard because, even though I’ve been in it, and I don’t think anyone could do it better than Rory Kinnear, personally, but I think lago is the most fascinating character. I wouldn’t do it because it could never live up to what he portrayed.

7R: He was so amazing.

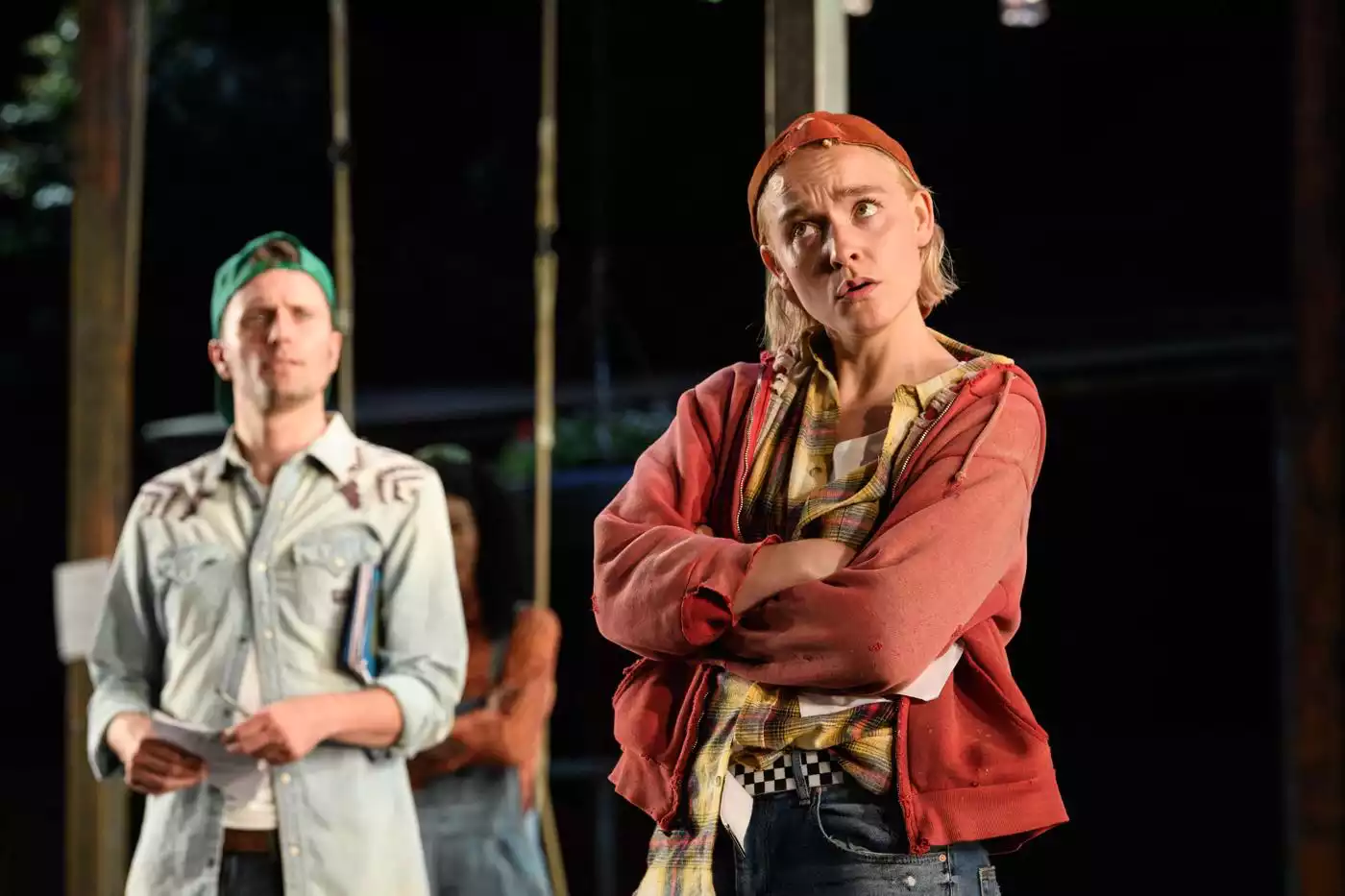

Olivia Vinall: He was so amazing. I think a lot of the Shakespeare comedies, too. I’ve done a lot of tragedy, but I really enjoy [the comedies]. It was so freeing doing As You Like It [in 2018]. We did it outside [at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre] in the summer. The joy of that!

- Olivia Vinall as Ganymede in As You Like It

- Olivia Vinall as Rosalind in As You Like It

7R: What are you working on next?

Olivia Vinall: Well, I was supposed to be starting a film. I’m not allowed to say what it’s about. We were going to be filming in Mexico, but because of COVID, that’s been postponed. I’m waiting to hear when that will start again. In the meantime, I’m just figuring out when that will be and then if other stuff can fit before it or around it. It’s exciting that theatres might start opening up again because I’d love to do a play soon. I was doing a play last year when we shut down here in the UK. It didn’t go on that night. We all did the warm up, and it was the half, and then it was like, no, you’re not going on.

7R: So it stopped before the run even got to start?

Olivia Vinall: We’d only done like three weeks of the show at The Globe in the [indoor] Sam Wanamaker [Theatre]. We felt like we were just starting. We all naively thought we’d be back on in a few weeks. And then we just never went back. I haven’t closed the lid on that. It took a while to feel like there was an end to it.

Where to watch Olivia Vinall’s work

The NTLive recording of Othello is available to rent on National Theatre at Home. It’s also available in the National Theatre Collection, which your library may have access to.

A recording of The Seagull is available in the National Theatre Collection. Check with your local library.

Sam Mendes’s productions of King Lear and Nicholas Hytner’s The Hard Problem were both recorded for NTLive though not currently publicly available.

The Woman in White is streaming on the PBS channel on Amazon. Roadkill is available on BBC iPlayer and on the PBC Channel on Amazon.

A Beautiful Curse is still on the festival circuit. Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter for updates on future screenings.

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch under-the-radar films with great actresses like Olivia Vinall at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.

Click here to subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter.