In this interview, legendary indie filmmaker Patricia Rozema sits down with us to discuss her works, from Cannes award winner I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing to her lesbian romance When Night is Falling to Kit Kittredge: An American Girl.

Read our extensive coverage of Patricia Rozema’s Mouthpiece (2018).

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

As an American, I felt a bit unqualified to interview a Canadian filmmaking legend like Patricia Rozema. I mean, this is one of the pioneers of the Toronto New Wave. She’s got one of the longest, most dynamic filmmaking careers in Canada, with films set everywhere from Regency Era England to a post-apocalyptic farmhouse and genres ranging from musicals to YA. She won the youth prize in Cannes’ Directors Fortnight program for her first film, I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987), when she was exactly my age — 29. But if my video chat with the director on a sunny Wednesday afternoon taught me anything, it’s that imposter syndrome is for suckers.

Fresh from a four-movie retrospective this spring, and now celebrating the upcoming release of I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987), White Room (1990), When Night Is Falling (1995), and Mouthpiece (2018) on Blu-ray — both courtesy of Kino Lorber — Rozema knows a thing or two about trusting your creative intuition. When we chatted, she had just finished teaching an MFA-level filmmaking class at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Rozema is every bit as brash and witty as her movies, but she’s also an earnest, generous collaborator. She’s inspired by her students. She fangirls over Wong Kar Wai. Even with her lecture hall hovering in the background of her Zoom screen, our conversation felt less like an interview and more like a catch-up over coffee. It was easy to lose track of time as we covered her early career, joked about lesbian stereotypes, and bro’d out over universal healthcare.

Seventh Row (7R): What’s the retrospective process been like? Did you get any interesting feedback on your films?

Patricia Rozema: People have been commenting on themes across my films, which I’ve always had trouble addressing because I think of them as all so different. One person observed, I thought really interestingly, that although the main characters were out of step with their environment, they were quite comfortable in themselves. So it was like a fish out of water, where the problem isn’t the fish; it’s the water. I liked that, and it just felt true.

There were a bunch of observations that I was very excited to hear. I recommend it highly. Make a bunch of films, and then, thirty-whatever years later, get people to comment on them. Which films stand out, and which fall back? The film that a lot of people dismissed in its time was White Room, and now several young critics and journalists have taken it quite seriously.

7R: The Kino Lorber restorations of White Room and When Night Is Falling are going to make those films widely available to people for the first time. How does it feel to have those early works out in the world again, and what do you think it is about them that still speaks to people today?

Patricia Rozema: It’s thrilling, these Blu-rays and 4K restorations up on big screens, the films being treated with such respect. It makes me feel fancy. I’ve also added a bunch of short films and new commentaries in some cases. It feels like a combination of my earlier self and my more recent self meeting. Mouthpiece is relatively new, and I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing is my first film. Both show a kind of absolute freedom, an unfettered openness and resistance to any kind of rules.

In Mermaids, I didn’t know what the rules were. I was so outside of the norm: I was a woman, first, in a world that didn’t take them very seriously as creators. I was a lesbian. That was unheard of in the Calvinist Christian world that I grew up with. I didn’t study film. I was just responding to my life and making what I wanted to see. And in Mouthpiece, I didn’t care what the rules were.

7R: What did you study, if not film?

Patricia Rozema: Philosophy.

7R: Can you tell me more about how one led to the other?

Patricia Rozema: One of my high school teachers actually taught something called “Man and Society.” In hindsight, it was philosophy. I think philosophy was a great place to come from for film because it’s about how ideas form.

I’m teaching film right now, and we’re really trying to impress upon them that film is just a pencil. You’re just drawing something. The technique, the machinery, that all keeps changing, and it should keep changing. But you need to control your craft. You need to be able to manage the clay that you’re sculpting with and know when it’s going to crack and how it’s going to dry and all these things. But still, what’s the germinating idea here? Constantly bring it back to the idea.

7R: What’s your favourite movie to teach right now?

Patricia Rozema: I’m not unpacking other films so much. I was asked what I’d like to teach, and I thought, okay, how did I learn most? I learned by doing. Sandra Oh came in to talk about directing actors, and Jeremy Podeswa, who’s a friend who directs, as we call it, zhuzh TV, came in to talk about that. I’m bringing in some inspiring, very, very accomplished people, and then we’re making some movies.

I spoke to some of my professors who really had an impact on me about what makes a good professor, and I believe that it’s listening. The worst thing would be if my students were to go, “Oh, Patricia says I have to cut here, Patricia says this should be the ending shot.” They have to find their own voices and define their own styles.

I was once having trouble finishing a film, and I had this big, very spirited discussion with a producer who felt it should go a certain way. I had the good fortune of being able to contact Jane Campion and said, “Would you look at it? Will you tell me what to do?” She said, “Sorry, I’m shooting. I don’t have time. But your body knows the answer.” I just said that today, in class. Someone had a choice between two shots to end the movie. And I said, “Your body knows the answer.” She knew instantly which one to choose.

7R: Which movie were you working on when you asked for that advice?

Patricia Rozema: Into the Forest (2015) with Elliot Page and Evan Rachel Wood.

7R: Speaking of queer people, I want to touch on When Night Is Falling, because I fear other journalists mightn’t. That movie did not blow up the box office, and you were also making it at a time when lesbian representation on screen was extremely different from how it is today…

Patricia Rozema: Can I ask you how representation is different now?

7R: I think that When Night Is Falling is an especially interesting coming-out story because it’s not a coming-of-age story. This woman is fully formed, and this pursuit of passion disrupts what many people would regard as a successful and stable life.

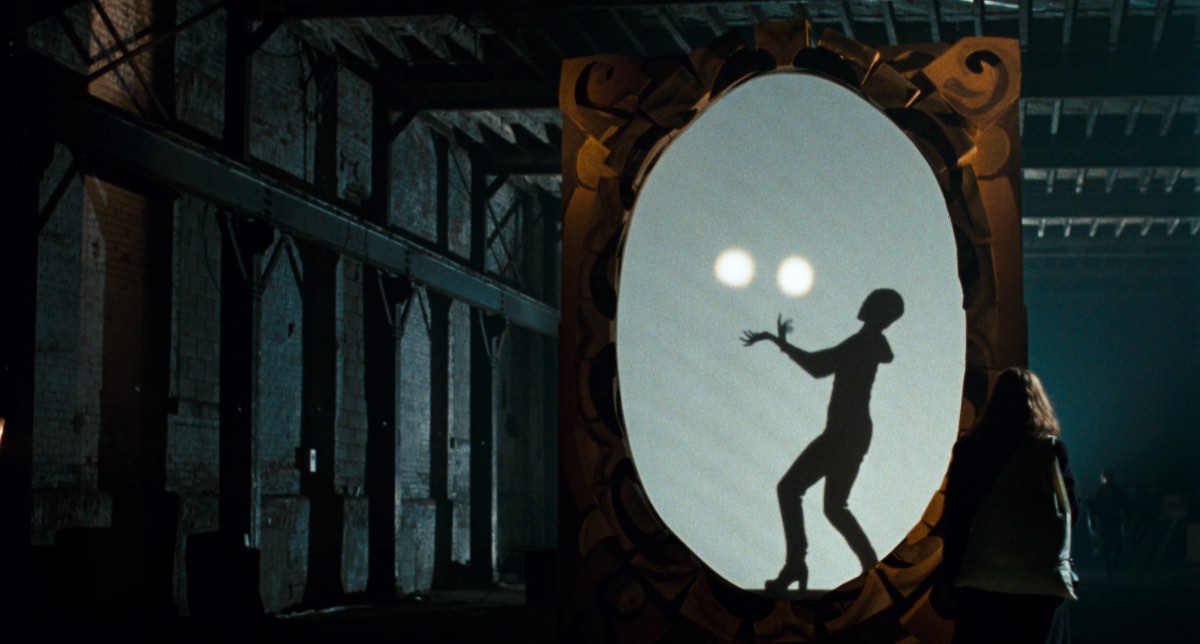

Patricia Rozema: Well, beginnings are exciting. Self-understanding is inherently dramatic. My first drafts of that film were kind of bleak. They had a woman who had the option to pursue a love and then didn’t. I often find that grief, loss, and disappointment make love seem more significant. That’s what was motivating my first draft of When Night Is Falling. And then I thought, oh, come on, we’ve had enough cautionary tales. I want to do something blindingly happy, almost impossibly happy. Even the dog comes back to life!

I just had a screening here in LA, and a woman stood up, and said, “I was teaching in the South, and I was teaching Sunday school. And then they found out that my best friend was more than that, and I lost my job. I lost my family at the same time, and no one would speak to me for ten years. And then I saw this film. It was the first lesbian film I ever saw. And I thought, ‘Oh, it’s going to be okay. There are people out there that understand, and it’s going to be okay.’” And she said, “I went from feeling dirty, from feeling flawed and broken, to being proud.” I don’t say that to say my film heals all wounds, but to know that you’ve made something that could give that to somebody else? Oh, my god, it’s the most deeply satisfying thing.

7R: That’s incredible feedback to get. I love that you touched on the ending of When Night is Falling, because when you kill the dog right at the beginning of your lesbian movie, I was like, “Oh, no! What has she done?!”

Patricia Rozema: I had one screening which was all lesbians, which was fantastic. My people. And then, when the dog died, the gasps of horror in the audience, I’ve never heard anything like it. It was hilarious. My girlfriend at the time of making it went back to Paris and became a distributor. She and her new girlfriend distributed that film.

7R: Classic.

Patricia Rozema: Yeah, we’re still good friends. And she reported to me later that Wong Kar Wai, one of the filmmakers that they also distributed, was in their office, and he saw the poster for When Night Is Falling. He said, “Oh, I love that movie,” which shocks and thrills me. He said when the dog comes back to life, that was his favourite part. It’s the lesbians and Wong Kar Wai that really appreciate that.

7R: I mean, who else do you need?

Patricia Rozema: That’s it. That’s all I care about. If they like me, I’m fine. I’m done. I can die.

7R: It sounds like you’ve gotten some very warm feedback on When Night is Falling. But I think because we have so few lesbian movies, books, etc., we as a community can be kind of hard on our own. I’m curious if that was part of your experience, as well.

Patricia Rozema: I remember it more for I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing. Some people wanted me to be more out. I’ve always been really out in my life, but [back] then, I was more careful.

I had one very surprising response. I was at a dinner in London, and there was this very glamorous art dealer. She didn’t know that I’d made When Night Is Falling. We somehow got talking about movies and lesbians and whatever. She said, “Have you seen this film, When Night Is Falling?” And I said, “Yeah.” She said, “Well, clearly, whoever made that has never slept with a woman.”

7R: No!

Patricia Rozema: So, yes, at least one person didn’t feel represented. It was also a biracial love story, and some people had a concern that the Black woman [played by] Rachel Crawford had been exoticized in the story. I wrote it thinking of two white girls and then cast for anybody, and she was great. I asked her, what do you think? Do you think we can do this story without addressing race? She was very thoughtful about it. She said I’d have to address it in the sequel, when they meet their families and have to decide where to live. But she said at the beginning, when you’re falling in love and you’re in the circus, it doesn’t matter. So I decided to go with that.

7R: That’s an interesting critique. It’s hard to separate how much exoticization just comes from being a member of the circus, but fair enough.

Patricia Rozema: But it was a circus that some people wanted to run away from! So it wasn’t necessarily a fantastic other.

7R: Right, that’s something that you grasp really well, the reality of being an artist and living in the world. The circus is failing. Pauline, in Mermaids, doesn’t even get that what she’s doing is art. The whole “starving artist” thing seems to come from a really authentic place. What’s it been like, on a practical level, to make independent films your whole life?

Patricia Rozema: When I grew up, I was taught how to save. So I saved like crazy. I literally ate cans of tuna for dinner many, many nights. I had this idea that if I could just get enough money together to do a down payment on some hole in the wall somewhere, then no one could throw me out.

No one was going to take care of me. I knew that I wasn’t going to have any support, so I would have to take care of myself. That was really it: I saved like crazy. I decided on a look that didn’t take a lot of money and decided on a way of life that was just dirt cheap. And then I worked really fucking hard.

I never expected that I would make money from the profession. I considered it like painting, and I thought that was sexy as can be, in a way that you do when you’re in your early years. And later, you kind of think, what? New clothes would be nice.

7R: Health insurance would be nice!

Patricia Rozema: Well, I’m in Canada.

7R: Canada, dude.

Patricia Rozema: Dude, that really makes a difference. Those kinds of social safety nets affect the art you make. If everyone hated my work, I would still have health care. If I was coming into my own in the US, I might have had bigger movie stars and then the films would have gone much farther if they had worked. But in Canada, I knew I would have more control over what the movie was saying and doing.

There are a couple of things I did for TV, which of course is not my final say, but everything that’s a feature, I’m behind every moment of it. Every shot, every sound, I’m completely responsible for it, for good or ill. If I’d grown up in the US, unless I’d found some kind of Medici, I might not have had that. I might have been thinking about genre, hooking the audience, and being more market-conscious than I was.

7R: This is a good segue into Kit Kittredge, your most commercial project. I’m fascinated that they hired a Canadian to make the first American Girl movie. Did you feel like an outsider at all in that process?

Patricia Rozema: I was brought into that project by Julie Goldstein, who I had met on Mansfield Park, so it didn’t feel like she was reaching out for a Canadian. She was an ally, and we’d worked together before. I was by no means the writer on it, but I did some tweaks to the script as we went. I called it my thinly-veiled socialist manifesto.

When I was doing the junket for the movie, I was hauled out of my Filmmaker magazine interview by the head of American Girl, and they said, “If you say one more time that this is your thinly-veiled socialist manifesto, you will not be doing any more interviews for our movie.” I said, “This was in my mind while I was making it! You can talk about what was in your mind, but you’re not going to control what I say was in my mind.” I remember Wally [Wallace] Shawn was thrilled with the questioning of capitalism. It was a time in America when the government just poured money into social projects. I thought it was so interesting that during COVID, people didn’t say, “Oh, is free enterprise going to save us now?”

Anyway, my experience on Kit Kittredge was fun. I had all these kids who had never acted, and you can only shoot them for a certain number of hours a day. There were animals, dogs. It was meant to feel like chaos. I had three cameras, so I could catch magic if it happened to happen. It was fun.

7R: I’m sure people will be curious to hear more about the cast. I wasn’t old enough to appreciate it when I first saw this movie as a girl, but in hindsight, this cast is stacked.

Patricia Rozema: That was the power of the brand! It also came together really quickly. Sometimes, when you’re asking people three, five months in advance or a year in advance, they don’t want to commit yet. But it was like, “We’re gonna shoot any minute because of Abigail’s schedule.” So we just approached Stanley Tucci, Julia Ormond, Wally Shawn, Chris O’Donnell, Jane Krakowski, Glenne Headly… Who else was in there? There was just an embarrassment of riches. It was so fun.

That was HBO’s power. You get into the system and you get answers, like, two days later. It was incredible. These actors all had children — I mean, almost all of them, except Wally Shawn. I said to Wally, “Do you have children?” He said, “No, I was never really good at that.”

I did a show for HBO as well, called Tell Me You Love Me, which was very graphically sexual. They were right around the same time. I felt okay about doing both of them because they were balancing each other out in a way. I have two children, and I wanted to do something for them, honour them in some way, and teach them some values in a way that not every movie for kids does.

7R: You have worked with some of the greatest Canadian actors. The figure of the Canadian woman has been a throughline in almost all of your films, and also the city of Toronto. It’s been fascinating to watch those things evolve in your films. As a filmmaker, and as a filmmaker revisiting things, what’s it been like to represent Canada?

Patricia Rozema: I’m proud of myself that I let Toronto be Toronto. Because the pattern was, for the most part, to hide the fact of where it is. If you’re trying to make a film that’s going to press all the buttons and get out there, you wouldn’t necessarily highlight the fact that you’re from elsewhere. I liked that I just embraced place. I just feel like it looks insecure, and like you’re trying to please everybody else, when you don’t.

The confidence to do that, or the will to do that, comes, again, from knowing that if you fail, you’ll still be okay. I grew up reading Margaret Atwood, who was so just out-there Canadian. Alice Munro wasn’t disguising her work as somewhere in Middle America. Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, and Neil Young weren’t pretending to be Americans, and they were doing just fine.

If my goal had been to do Marvel movies, I might have taken a different path. But my goal was never that. I had this idea very young, like in my early twenties, where I was like, wouldn’t it be a great life to just sit in the nursing home and have a row of film cans — of course, it was cans, then — beside me, and they’re all different people and they’re all different ideas and they all they add up to a worldview? I’ll never get too good at that. I wouldn’t tire of it. It just seemed like, if I could get away with that as a life, and have a sandwich a day not die in the gutter, that’d be very good.

7R: Your characters’ dreams influence their lives significantly. Do your dreams influence your life, whether creatively or otherwise?

Patricia Rozema: I wish they did more. I’m not the first to say this, but if my subconscious is speaking to someone else’s subconscious, without my consciousness getting in the way or distorting that, then that’s a powerful interaction. If I can add my consciousness to that, add the intellect to that, then it’s even more layered. Respecting the ineffable, the unspoken, and the things we don’t understand about ourselves is such a precious thing, and very hard to do.

In Mansfield Park, there’s a moment at the end where everyone just pauses, and they consider alternate lives. That was from a dream. I remember I was trying to shoot it and Harold Pinter was like, “I don’t know what you’re going on about here,” and I said, “You know what, Harold? I’m gonna be honest here. I don’t either, but I really like it.” And he said, “I can respect that.” He got the need to honour the things that have a pull but that aren’t explainable. I can come up with explanations and motivations, but these things come after the fact. People say never report your dreams, but I love it. I love those images. I find them thrilling.

7R: What is something that inspired you today?

Patricia Rozema: One of my students’ short films. It was from somebody who’s wildly intelligent and intellectual. I’ve been thinking, well, maybe they’re meant to be an academic — which I have great respect for, but it isn’t the same emotional skill set as being an artist. That was my thought after I saw their first cut. Then I saw their second cut and wanted to cry. The perfectibility of these stories is exciting because I go with them. I go through all of these, like, “Oh dear, I’ve had so much hope, but this is really clunky and it’s never gonna sing.” And then you just keep at it, keep healing it, keep re-understanding. You have to learn the same lessons over and over and over again.

That’s what religion was good at. Sometimes, I feel like we threw the baby out with the bathwater — and there was a lot of stinky bath water, let’s say it — but religion had a system of revisiting values that were shared, and reaffirming them. We’ve all had the experience of having a film that has just revolutionized our minds and our hearts. It’s a paradigm shift, and then a week later, you go, what was that about? What was the title?

I sometimes wish there was something like church, but without all the awful bits, where we got together with people and didn’t have to set it up. It was just there. You go to this place at this time, and people you know will be there. You may sing together, you might hear someone you respect talk about things higher than your own little career, and you’ll contemplate things larger than your little self. I’d go there.

7R: Well, it sounds like you’re building that for other people.

Patricia Rozema: Oh, that’s a lovely thing to say. I hope so. That’s a lovely thing. I never thought of that.

Related reading/listening to our interview with Patricia Rozema

More interviews with Patricia Rozema: Watch our masterclass with Patricia Rozema. Read our Mouthpiece interview with Patricia Rozema and her co-writers/co-leads.

More interviews with Patricia Rozema’s collaborators: Watch our masterclass with Mouthpiece co-creators Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava. Read our interview with Mouthpiece editor Lara Johnston. Watch our masterclass with Mouthpiece cinematographer Catherine Lutes.

Pat5ricia Rozema on the podcast: Listen to our ‘Dead Mothers’ episode on Mouthpiece, Stories We Tell, and Louder Than Bombs. Listen to our in-depth episode on Mouthpiece, one of our earliest podcast episodes.

More 2SLGBTQIA+ coverage, like When Night Is Falling, I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing, etc.: Read all of our 2SLGBTQIA+ film coverage.