The 2016 season at Santa Cruz Shakespeare offers a terrific production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and a thought-provoking gender-swapped Hamlet.

In its third season as the reinvented Santa Cruz Shakespeare and its first at its new home in Deleveaga Park, the company continues to push the boundaries in its productions of Hamlet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. While colour blind casting has always been a feature, this year they’ve upped their gender blind casting: Hamlet, Polonius, and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are all played by women. Peter Quince has been transformed into Penny Quince (Kate Eastwood Norris) and Hermia’s patriarch has become a matriarch (Carol Halstead). It’s a practice Santa Cruz Shakespeare tested out on a small scale last year with a female Leonata to mixed effects, but which works here like a dream.

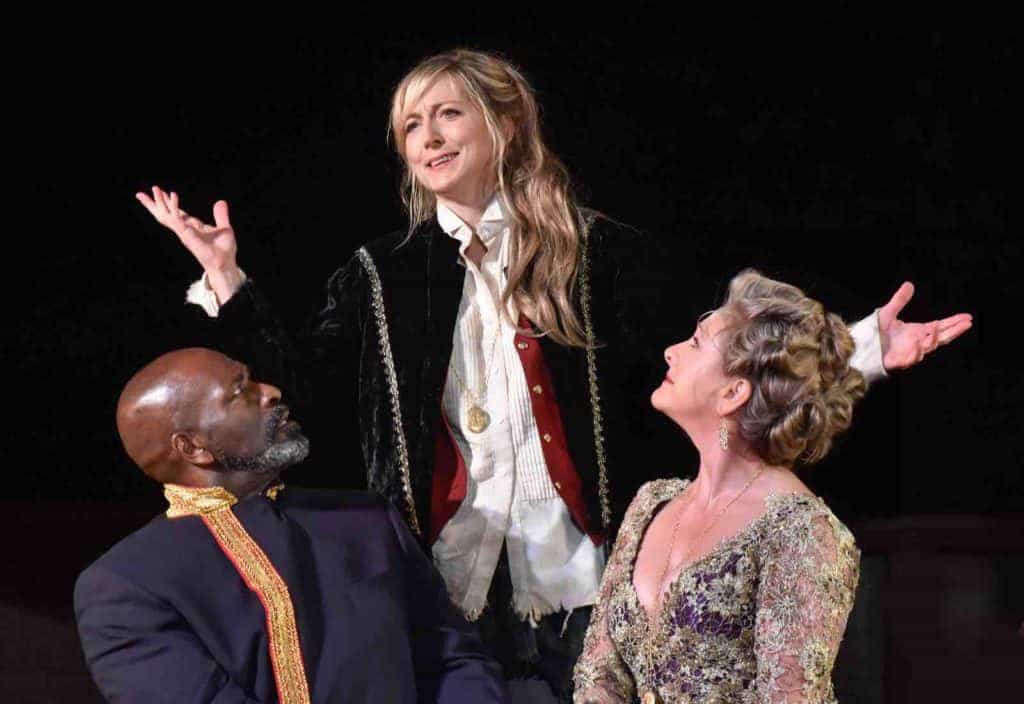

In Hamlet, this “blind” casting leads to some interesting new interpretations. As Ophelia (Mia Ellis) and Claudius (Bernard K. Addison) are the only two black characters at court and Claudius seems much more concerned with Ophelia’s madness than Hamlet, we’re left wondering if they might be related. Could Claudius’ second-in-command, a female Polonius (Patty Gallagher), have once been something more? Casting a cis-female Hamlet — compared with Maxine Peake’s transgender Hamlet — also invites us to question why Hamlet is so obsessed with Ophelia’s chastity and fertility.

Terri McMahon’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream opened first this year, and it’s clear that this is meant to be the company’s flagship show: it’s perfectly cast, while the same can’t be said for Hamlet. Santa Cruz Shakespeare hires a company each year, each actor taking a role in both plays. Mia Ellis’ regal countenance and powerhouse voice make her an ideal Hyppolyta and Titania, but she’s ill-suited to the meeker Ophelia. While Bernard K. Addison steals scenes as Nick Bottom, but his more serious Claudius is dead on arrival, almost devoid of personality.

The spotty casting isn’t helped by the indistinguishable costumes, with the result that characters bleed together. Hamlet (Kate Eastwood Norris), Horatio (Mike Ryan), Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern are all clothed in the same school uniform, which is baffling. Are we meant to believe that there’s a uniform at Wittenberg — and Hamlet wears it at home? How are we to differentiate between Hamlet’s childhood friends, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and his newer university friend, Horatio, if they all dress the same way?

Fortunately, Kate Eastwood Norris has a commanding stage presence as Hamlet — though sometimes almost too dominating for us to believe that she finds Denmark a prison. Not enough care is taken with the soliloquies, which too often sound like recited speeches rather than moments when Hamlet is wrestling with her thoughts, but Norris is still incredibly watchable.

The payoff for Norris’ confident Hamlet comes in the last couple of acts when Hamlet returns to Denmark from England. So often, the interactions Hamlet has with the gravedigger (Larry Paulsen) and the palace servants feel like filling time. But in this production, each is weighted with meeting. The lowly gravedigger is the first character who can challenge Hamlet verbally or territorially, insisting that the grave is his. While Hamlet was sparring with powerful figures like Polonius and Claudius in the first half, she’s now been reduced to making a meal of the lower ranks, suggesting her downfall is already well underway.

Mullins’ production is the first time I’ve ever seen the gravedigger serve more than just comic relief. Hamlet may be laughing along with his jokes, but inside the grave lies Hamlet’s lost childhood: his companion Yorick and his first love Ophelia. In an ingenious piece of set design, the grave lies just underneath a floorboard, hidden beneath a trap door. At the end of the scene, it gets completely covered, with no signs of it remaining, not even excess dirt. It’s as if the action of the entire play has been taking place over a grave that we — and the characters — didn’t even know was there.

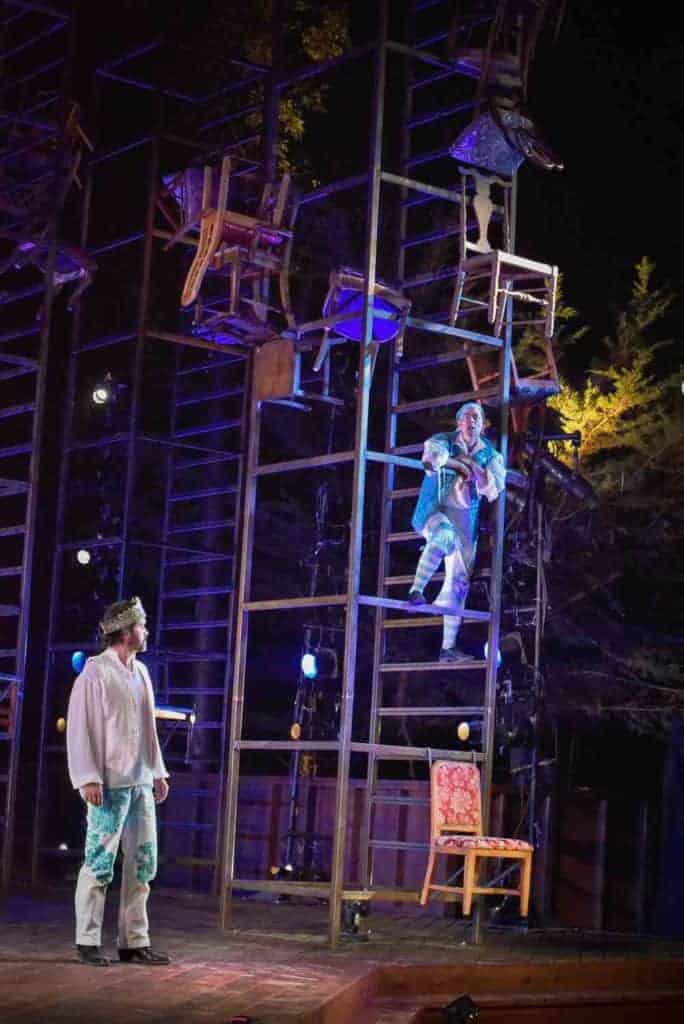

Although Dream was altogether a strong, amusing, and seamless production, it stands out for its incredibly effective use of metatheatre. Almost all of the action in the forest plays out before Oberon (Cody Nickell), and sometimes some of his fairies, who serve as an audience to laugh at the young lovers’ foibles. Oberon sits on a bed of stacked chairs and occasionally interferes, freezing the action, feeding the young humans lines. He’s the architect of the mess they find themselves in, albeit by accident thanks to his poor instructions to Puck (Larry Paulsen), and he’s also the one who helps resolve it. When the final act rolls around with the performance from The Rude Mechanicals, their bad theatrics aren’t merely there as tacked on comic relief; it’s a role reversal. Now that the lovers are happily settled, they can laugh at the actors still trying to figure it out — blissfully unaware that they themselves were providing this kind of entertainment for the fairies just moments before.

Dream’s one misfire is that it fails to address how its interpretation clashes with the text itself. The production never addresses how Oberon’s control over the lovers screams of the patriarchy, the very same kind of power that Hyppolyta was deeply uncomfortable watching Theseus (Cody Nickell) display towards Hermia (Katherine Ko) and her lover (Kyle Hester). Given the parallels the production draws so well between the doubling of Hyppolyta/Titania and Theseus/Oberon, it’s a missed opportunity, which risks leaving us with a sexist reading of the production.

Now that recorded theatre is becoming more common, it’s begun to noticeably influence the productions at Santa Cruz Shakespeare. The stacked chairs that hang from metal columns in A Midsummer Night’s Dream are right out of the National Theatre’s As You Like It earlier this year, which created a creepy Forest of Arden with chairs hung from the ceiling like trees. The gender-bending casting in Hamlet likely takes its cues from Sarah Franckom’s recent production, which also gender-flipped Polonius and Hamlet, to somewhat similar effect. And Julie Taymor’s fingerprints are sprinkled over A Midsummer Night’s Dream, from the balletic fight between the lovers in their final confrontation to the costuming and casting of Snug (Daniel Fenton Anderson) and his portrayal of the lion. The many great, unique touches, in each production are their selling point, but it is interesting to see how they are in conversation with other modern Shakespeare productions.