Orla Smith interviews The Farewell director Lulu Wang about making cinema of her own life and framing a family.

Review: Midsommar is a chaotic, visceral horror

Orla Smith reviews Ari Aster’s Midsommar, an exquisitely crafted horror with innovative sound design that unfortunately struggles to come together thematically. Listen to our podcast episode about Midsommar here.

Approaching center frame in The Souvenir

In The Souvenir, Joanna Hogg demonstrates Julie’s development from a shy observer to the main character in her own story through the way Julie occupies the room and the frame. This essay is a sneak preview of the new ebook on the film, Tour of Memories: The Creative Process Behind Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir. Get […]

Sundance London ’19 Capsule Reviews

Orla Smith recaps the best films of the Sundance London Festival, including Animals, Corporate Animals, The Farewell, and The Nightingale.

5 reasons we’re grateful for Joanna Hogg

In anticipation of our book on The Souvenir and Joanna Hogg, we reflect on all the reasons why this British director is one of the best. In the meantime, sign up to our Joanna Hogg challenge! Joanna Hogg helped give us Tom Hiddleston Hogg saw talent in Tom Hiddleston long before most of the film […]

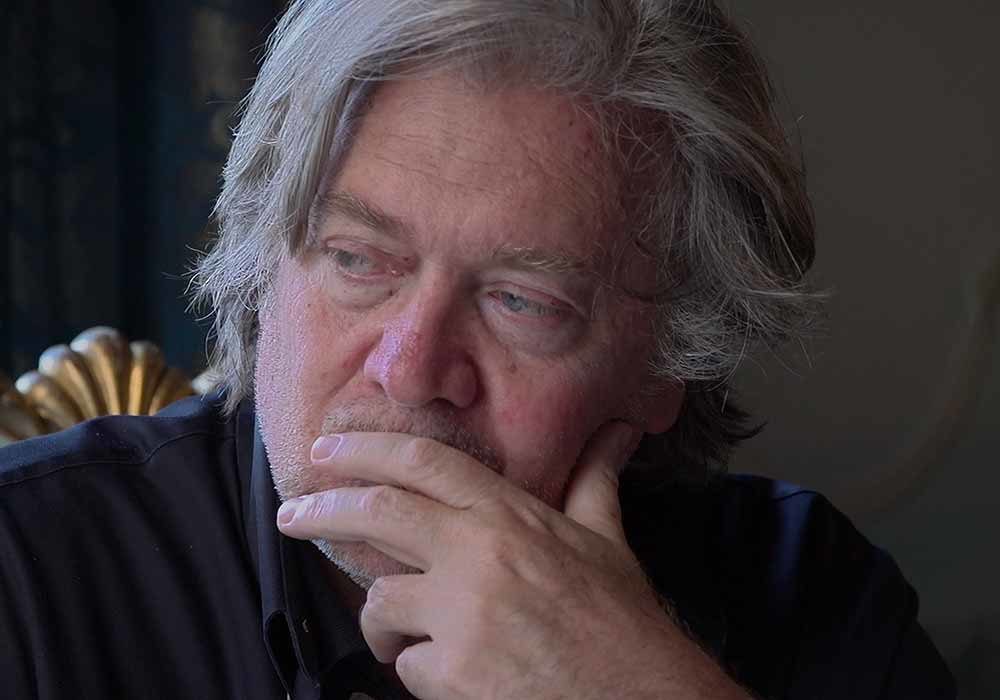

Klayman on filming Steve Bannon in The Brink: ‘Let him underestimate me and let me never underestimate him’

Alison Klayman discusses her new documentary, The Brink, a character study of Steve Bannon that spans a year. The Brink begins with Steve Bannon discussing the mechanics of Nazism and Hitler’s rise to power. He’s critical, of course — no political figure wants to be seen praising the literal Nazis — but the irony is […]