Merchants of Doubt takes an in-depth look at how the same public relations experts — these “Merchants of Doubt” — who helped tobacco companies persuade the world, in the 1950s and 1960s, that cigarettes weren’t harmful to health, even though the tobacco companies had done their own very good scientific studies that proved the opposite, were […]

Best of The Seventh Row

Great Movies: Oslo, August 31st and loneliness in the city

Joachim Trier’s brilliant and moving Oslo, August 31st is as much about its protagonist as it is about his generation and his city. Listen to our podcast on Oslo, August 31st here.

Don’t be fooled by the title, Fifty Shades of Grey is Anastasia’s film

Fifty Shades of Grey is far more interested in Anastasia’s thoughts and conscious decisions than in giving Christian even a semblance of a personality.

The 10 best film posts at The Seventh Row in 2014

The first full year at The Seventh Row has been a big one, with coverage of Sundance, Cannes, The San Francisco International Film Festival, and the Toronto International Film Festival. Here’s a look at the best film posts at The Seventh Row in 2014, which includes both reviews and interviews. 1. Review of “Boyhood”: In […]

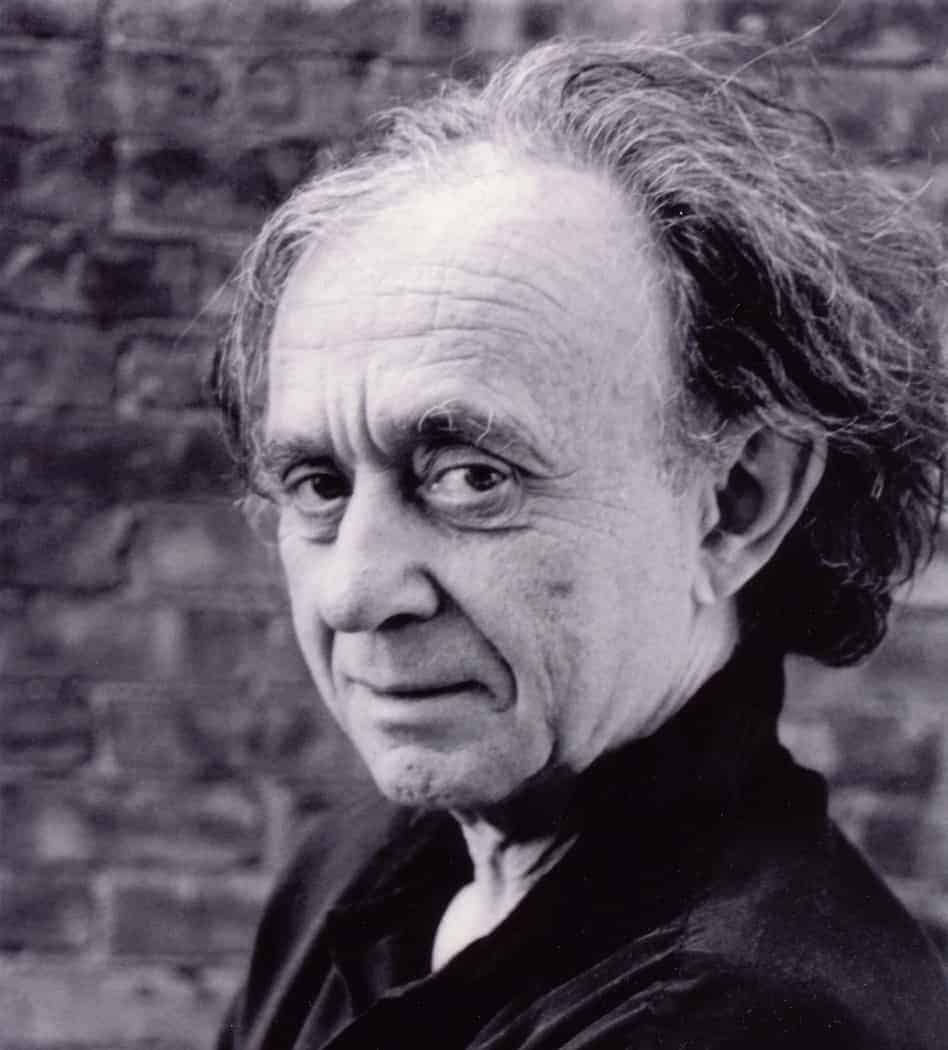

Frederick Wiseman on his new film National Gallery

His latest film, “National Gallery,” which premiered in the Director’s Fortnight at the Cannes Film Festival in May, takes a look at the inner-workings of London’s renowned art museum. The film is a fascinating look at one of the greatest art museums in the world, its role in the community, and how the paintings it houses continue to speak to us.

The Imitation Game: cracking the Nazi code and the human one

Benedict Cumberbatch stars as Alan Turing in The Imitation Game, an engaging but often silly look at the team who cracked the Enigma code.