By chasing after a PG13 rating, Mockingjay Part 1 has lost much of the moral ambiguity that made the books so interesting.

Best of The Seventh Row

Eddie Redmayne on Stephen Hawking and shooting out of order

In The Theory of Everything, Eddie Redmayne (My Week with Marilyn and Les Misérables) gives an impressively detailed performance as cosmologist Stephen Hawking. The biopic chronicles several decades in Hawking’s life – and his relationship with his wife Jane (Felicity Jones) – from his time as a Physics Ph.D. student at Cambridge, where they met and he […]

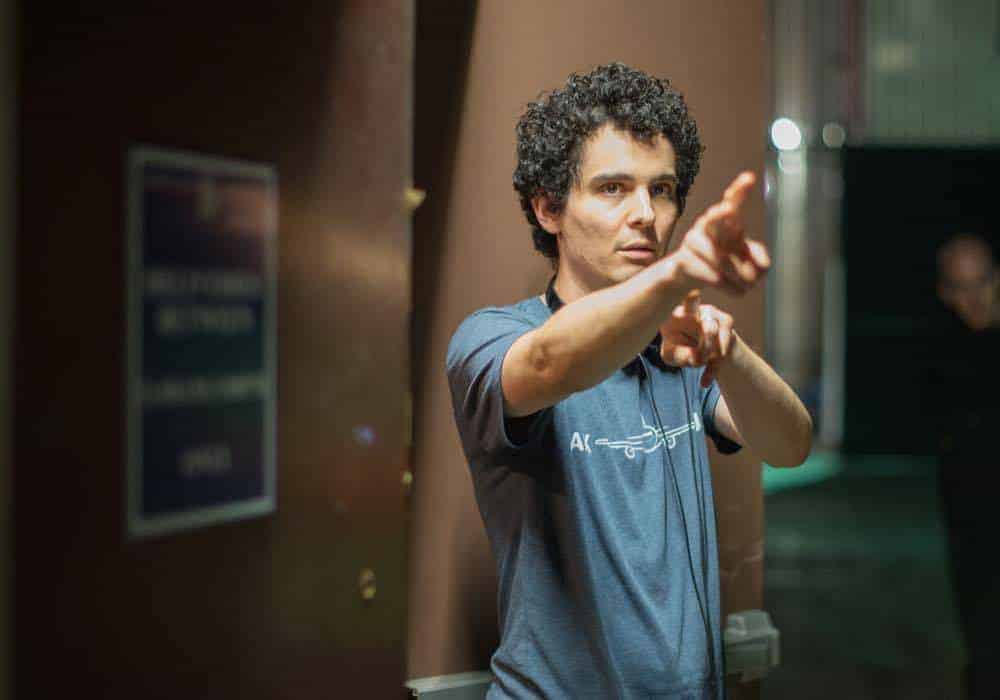

Director Damien Chazelle talks jazz and Whiplash

Director Damien Chazelle discusses Whiplash, jazz drumming, the bubble of big band jazz, and his approach to depicting jazz on screen.

Radcliffe and Kazan charm in The F Word or What If friends fall in love in this Toronto-set film

Starring Daniel Radcliffe and Zoe Kazan as a pair of Torontonian friends, Michael Dowse’s film The F Word (or What If, as its known stateside) asks, what happens when you meet someone you really connect with, and want to hold onto, when dating isn’t an option?

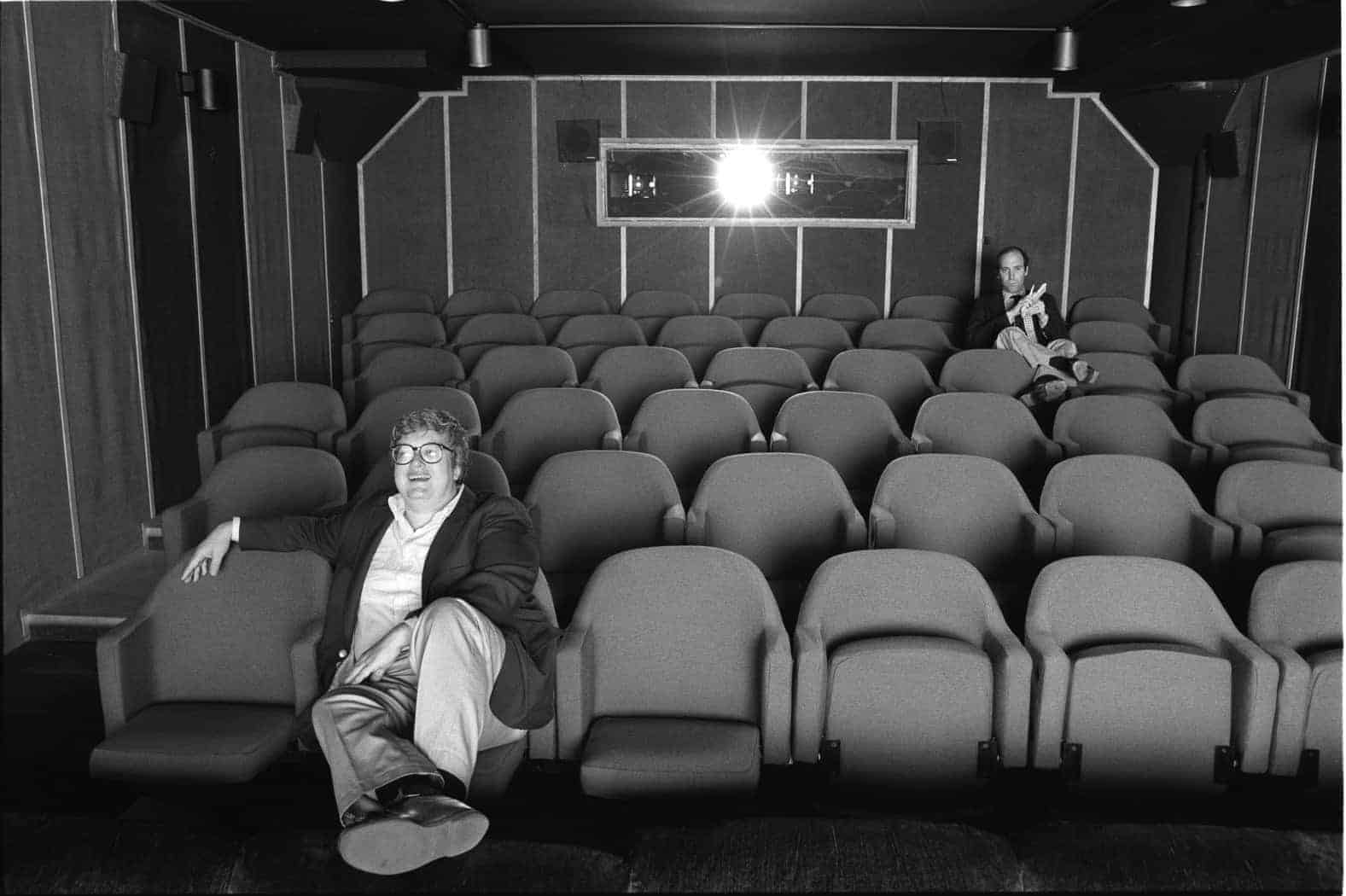

Life Itself: After a life at the movies, Roger Ebert lives on in the movie of his life

I grew up watching “Siskel and Ebert and The Movies.” It was a weekly ritual in my house, helping us decide what to see that weekend. The show struck something deep, and inspired me to start writing film reviews at a very young age: I was in grade 6 and I started my own magazine. It was through their television show that Siskel and Ebert became the world’s most powerful and influential film critics.

Sam Mendes delivers a lucid, dark, and funny King Lear for NTLive

Sam Mendes’ NTLive King Lear is an almost flawless production of the play at the National Theatre, which was broadcasted live to cinemas worldwide. The phenomenal Simon Russell Beale stars as a megalomaniac Lear who is slowly losing his mind.