Alex interviews legendary theatre director Marianne Elliott about directing for stage vs. screen and her first film, The Salt Path.

British Cinema

Ep. 143. The Old Man and the Land and the line between cinema and radio play

In this episode of the podcast, Alex

Heeney reviews and discuses the British independent film The Old Man and the Land, which stars Rory Kinnear and Emily Beecham.

TIFF 2024 Ep.6: Ralph Fiennes x 2: The Return and Conclave

Alex discusses two Ralph Fiennes films at TIFF 2024: Edward Berger’s Conclave and Uberto Pasolini’s The Return.

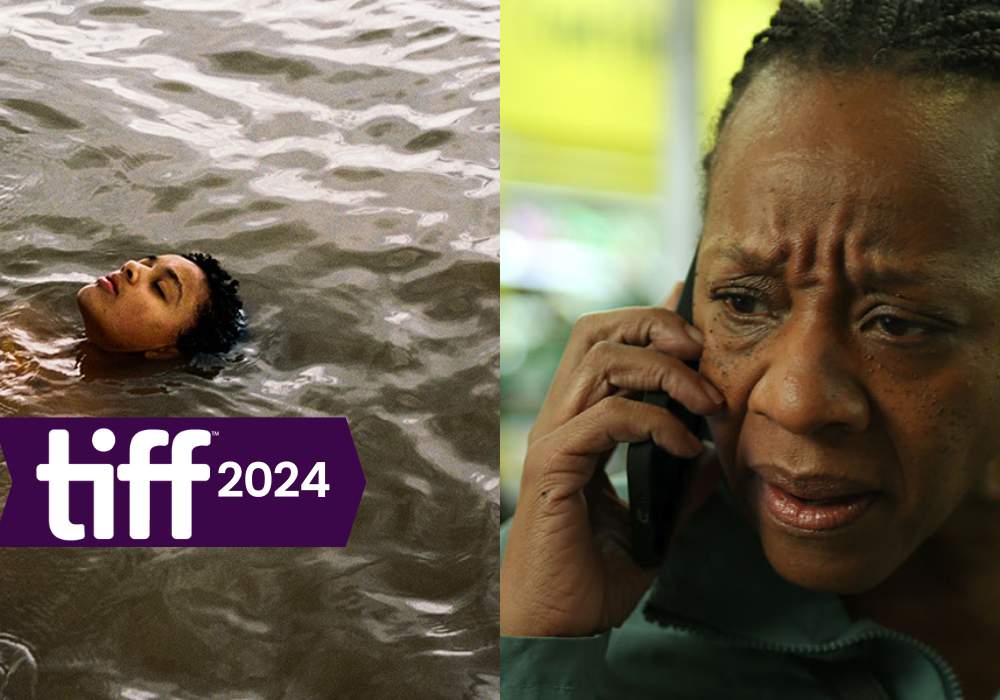

TIFF 2024 Ep. 4: British social realism: Andrea Arnold’s Bird and Mike Leigh’s Hard Truths

In this episode of the TIFF 2024 podcast, Alex discusses two new works from British social realist filmmakers Andrea Arnold and Mike Leigh: Bird and Hard Truths.

Film Review: Ken Loach’s The Old Oak

Alex Heeney reviews Ken Loach’s The Old Oak about finding solidarity between former British miners and new Syrian refugees in a small town.

Film Review: Wicked Little Letters is predictable fun

Thea Sharrock’s Wicked Little Letters is the kind of film you can enjoy with your mum and immediately forget about afterward.