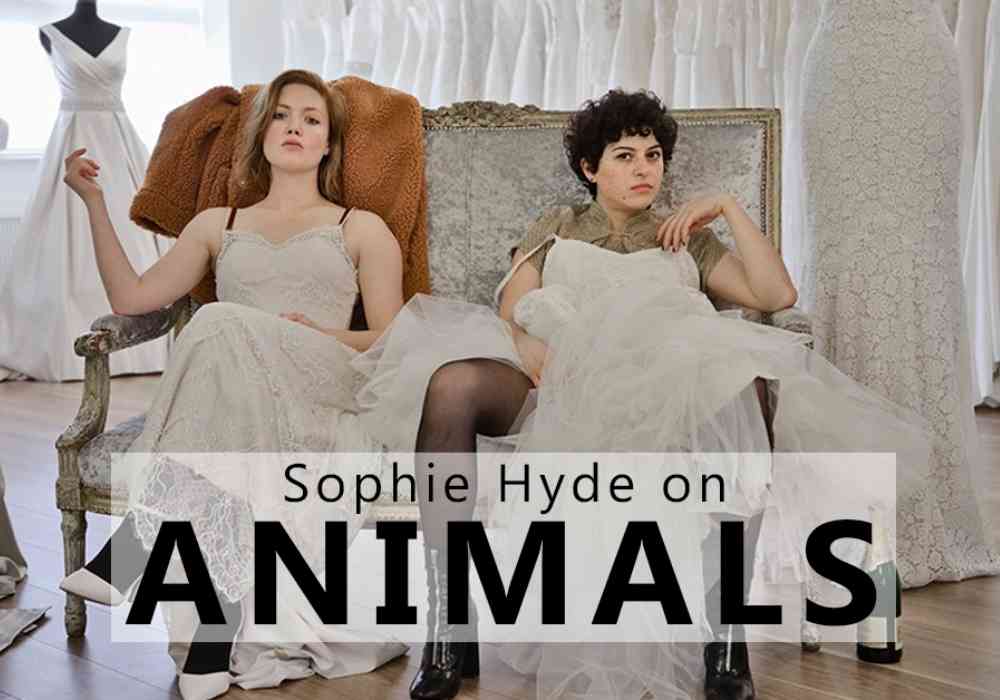

Animals director Sophie Hyde on her complex, sprawling coming-of-age film starring Holliday Grainger and Alia Shawkat.

Sundance London 2019

An interview with Lulu Wang on framing a family in The Farewell

Orla Smith interviews The Farewell director Lulu Wang about making cinema of her own life and framing a family.

Sundance London ’19 Capsule Reviews

Orla Smith recaps the best films of the Sundance London Festival, including Animals, Corporate Animals, The Farewell, and The Nightingale.

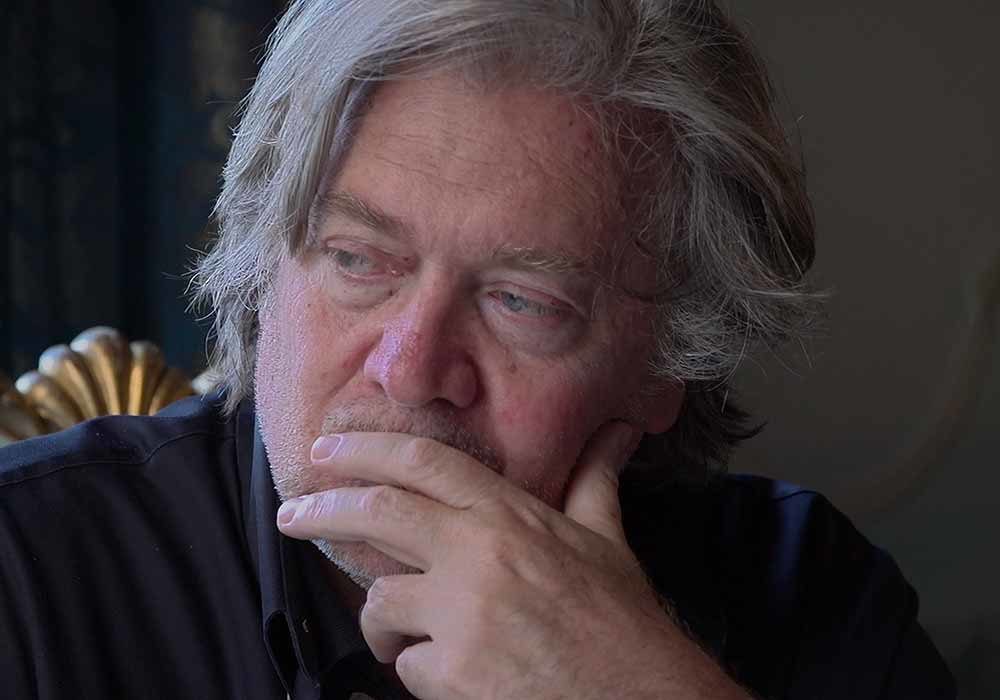

Klayman on filming Steve Bannon in The Brink: ‘Let him underestimate me and let me never underestimate him’

Alison Klayman discusses her new documentary, The Brink, a character study of Steve Bannon that spans a year. The Brink begins with Steve Bannon discussing the mechanics of Nazism and Hitler’s rise to power. He’s critical, of course — no political figure wants to be seen praising the literal Nazis — but the irony is […]

Shola Amoo on his stylised, subjective coming-of-ager, The Last Tree

In this interview, Shola Amoo discusses The Last Tree, making a highly subjective coming-of-age tale that’s set over three distinct locations that were important to him in his own teen years. One of the best coming-of-age stories at the 2019 Sundance London Film Festival was Shola Amoo’s semi-autobiographical sophomore feature. The Last Tree tells the […]