On the podcast, Alex recommends Laura Piani’s Jane Austen Wrecked My Life, a witty and warm film with a touch of melancholy about a woman getting unstuck.

World Cinema

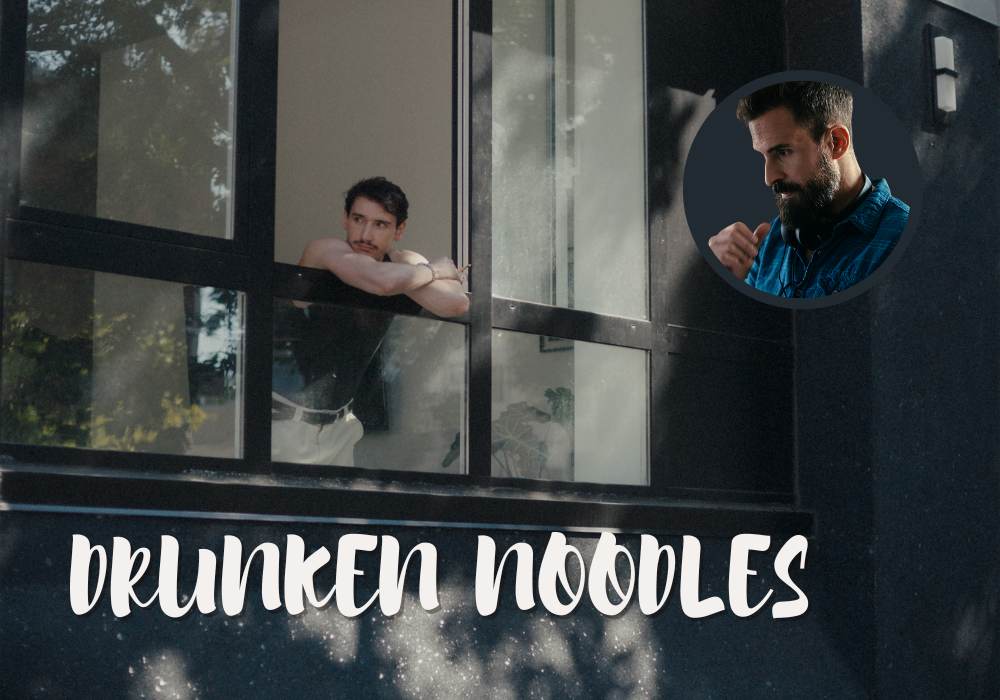

Interview: Lucio Castro on Drunken Noodles

In this interview, Lucio Castro discusses the total freedom of low-budget filmmaking for his queer Cannes ACID film Drunken Noodles.

Film Review: Pauline Loquès’s Nino at Cannes

Alex Heeney reviews Pauline Loquès’s feature debut, Nino, starring Théodore Pellerin, which screens in the Critics’ Week sidebar at Cannes. The film tells the story of a twentysomething man’s nervewrecking weekend after he’s diagnosed with c

ancer and before he starts treatment.

Film Review: Alice Douard’s Love Letters

Alex Heeney reviews Alice Douard’s debut feature Love Letters, which screens in the Critics’ Week sidebar at Cannes. The film tells the story of a queer woman in 2014 whose partner is pregnant with their child, and the paperwork involved with becoming her daughter’s legal parent.

Interview: Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne on The Unknown Girl

Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne discuss the making of The Unknown Girl, the sound design, and creating reality on screen.

Ep. 171 Navigating Cannes beyond the competition

On the podcast, Alex unveils the inner workings of all of the lesser-known sections of the Cannes Film Festival beyond the competition. She also talks about the many great films that have screened outside the competition in the past and what she’s looking forward to this year.