Charlène Favier’s Cannes-selected debut, Slalom, is a tense pas-de-deux between a 15-year-old professional skiing star, Lyz (Noée Abita) and her coach, Fred (Jérémie Renier).

World Cinema

Charlatan draws parallels between a faith healer and communism

Agnieszka Holland’s Charlatan tells the story of Czech herbalist and healer Jan Mikolášek to draw parallels with post-war communism.

Guillaume Canet shines in Au nom de la terre (In the Name of the Land)

Au nom de la terre (In the Name of the Land) tracks farmer Pierre Jareau as he struggles with increasingly crippling debt and his mental health declines.

Anne Fontaine’s psychological drama Night Shift (Police)

Night Shift looks at the inner lives of three police officers who take the night shift together. The film screens at Cinemania across Canada on Nov 22. Tickets are available here.

Antoinette dans les Cévennes is a showcase for Laure Calamy

Caroline Vignal’s Antoinette dans les Cévennes is a mid-life coming-of-age comedy starring the great Laure Calamy.

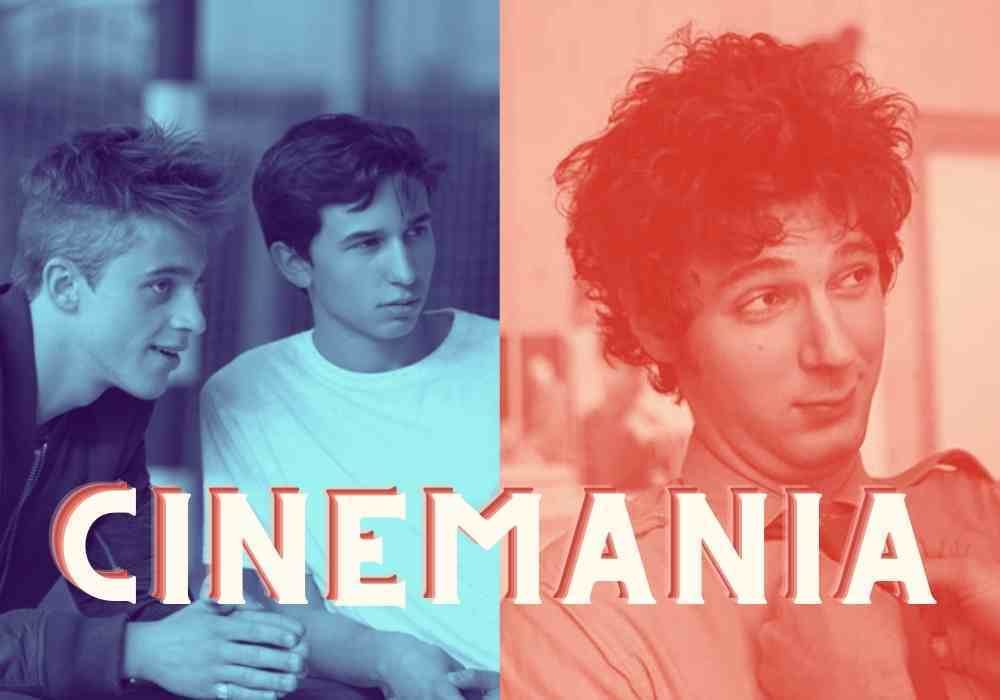

Are boys OK? Un vrai bonhomme and Mes jours de gloire at Cinemania

Un vrai bonhomme (Man Up!) and Mes jours de gloire are both coming-of-age stories about boys who are ill-equipped to cope with their mental health issues.