Writer-director Alexandra Therese-Keining discusses her sophomore film, Girls Lost, a smart and sensitive exploration of gender, gender performance, identity, femininity, and masculinity.

This is an edited version of the article originally published on September 19, 2015, as part of our TIFF15 coverage. Girls Lost will be available on DVD and VOD (including iTunes, Vimeo On Demand, and WolfeOnDemand.com) in Canada and the U.S. as of December 13.

Writer-director Alexandra Therese-Keining’s sophomore film, Girls Lost, is a smart and sensitive exploration of gender performance and identity. It was also one of the best films to screen at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival. The film follows a tightly knit trio of fourteen-year-old girls — Kim, Momo, and Bella — who face constant, sexualized bullying by the boys at their school. They idly wish they were boys, thinking this would free them from misogyny.

Their wish unexpectedly comes true thanks to a magical flower’s sap, which when ingested, temporarily transforms their bodies into a male form. The experience is freeing for Kim, who has always felt trapped in a body that wasn’t really hers, even as she’s forced to confront the consequences of his bad decisions that are driven by elevated testosterone levels. They all gain confidence from the experience and learn about the fragility of masculinity, but only Kim wishes to make the transformation permanent.

Magic realism allows Therese-Keining to set a sensual, almost dream-like tone, which enables the film’s nuanced, boundary-crossing gender explorations. Occupying a boy’s body allows Kim to chase after an object of desire, the bad boy Tony, a deeply homophobic but sensitive boy whose insistence on seeming tough makes him emotionally volatile and dangerous. But it also has unexpected consequences for the sapphic romance between Kim and Momo, who prefers Kim in a girl’s body.

The Seventh Row sat down with Therese-Keining to discuss adapting the film from the Swedish best-seller Boys, developing the film’s aesthetic, and creating some of the film’s most memorable scenes.

Seventh Row (7R): Girls Lost is based on a book, Boys, which was a big hit in Sweden. How did you get interested in adapting the book? What were the challenges of adaptation?

Alexandra Therese-Keining: After my last film, I was sent a lot of scripts that were pretty romantic dramas. Then, the producer of the company that made the book called me and said that I should really read this book. So I did. I just completely fell in love with the whole magic realism of it. I always loved films that had one foot in reality and another in a different dimension.

At the same time, I was reading the American writer Judith Butler. She has really interesting thoughts about gender performativity, where you can act your sex. You’re not actually your sex from the beginning. You use different kinds of attributes to act, to become someone — to become a boy, to become a girl. That really made me interested in how I could find that feeling in the characters and in the story.

[clickToTweet tweet=”The notion was it’s easier to be a boy and then…she understands that that’s not the case at all.” quote=”The notion was it’s easier to be a boy and then…she understands that that’s not the case at all.”]

7R: How did you think about what the differences between boys and girls, and the performance of being a boy or a girl?

Alexandra Therese-Keining: In the first act, the [girls are] really looked upon by their male peers as sexual objects. Every day, in school, they’re being called “cunts” and “whores”. People tease them about their breasts. It’s all about their femininity and their womanhood. They’re being diminished as people. They’re just chattel, just a body. To me, that was really interesting: what would happen if you put boys in the same situation?

I think the notion was that it’s easier to be a boy. Then, when Kim falls in love with Tony, she understands that’s not the case at all. Boys also have a lot of difficulties and problems. When I wrote the screenplay, people were saying, “Well, what are you saying? Are you saying it’s easier to be a boy, or…?” There were a lot of interesting discussions that arose during that time. When people see the film now, they might [initially] think that’s the case. Then, they see that the film is moving into a darker kind of area.

[clickToTweet tweet=”I always loved films that had one foot in reality and another in a different dimension.” quote=”I always loved films that had one foot in reality and another in a different dimension.”]

7R: Tony is such a rich character because that performance of masculinity is so key to his persona, but also we really get to see him being vulnerable and conflicted. How did you think about writing him, both as a romantic figure with a cigarette and the more complex figure he becomes later?

Alexandra Therese-Keining: I had to struggle for him a lot when I wrote the screenplay. The investors didn’t get him. They thought he was really difficult, and they wanted to erase all the scenes where he’s vulnerable, where he’s just a boy, where he’s just crying. I really felt that those scenes were the scenes that made him the character that he is. I think those few small scenes just make him more complex. You understand the struggle that he’s going through.

Read more: ‘A film about a feeling’: Adam Garnet Jones talks Fire Song >>

The actor had a really great understanding of how to convey those feelings of the character, that kind of lost, childlike quality that he has. The power that he gets from his effect on Kim, and it’s a real power play, it’s really interesting to watch.

7R: You get such sensitive performances from your young male actors. They don’t conform to any stereotypical gender norms. How did you do that?

Alexandra Therese-Keining: It’s all in the casting. I always have a notion of what I want to do. When I’ve found the right actor, it falls into place. All the boys were really sensitive towards each other, and they brought a lot of energy and intensity. They had great chemistry, right from the beginning, that just grew and grew and grew.

7R: How did you develop the aesthetic for the film? It’s full of beautiful colours and beautifully shot.

Alexandra Therese-Keining: The screenplay is based on Boys, a very beautiful novel, which has very poetic language. You can almost feel the visuals and the scenery. It’s really inspiring. It’s almost like a fairy tale, this film. We had quite lengthy discussions of how we would light it and what kind of colours it would use. We only shot at night, in about six weeks — all night shots all the time — to get that kind of magical feeling during dawn.

Read more: Stephen Dunn discusses Closet Monster, magic realism, and internalized homophobia >>

7R: What kind of discussions did you have about the colour palette and how to achieve that look of a fairy tale?

Alexandra Therese-Keining: We wanted all the background in the back of the actors and the extras to be really grayish. Watch closely, they have grey clothes. In the beginning, the girls have, not strong colours, but somewhere in the middle, and then the clothing changes, becomes darker. The costumes become black, almost greyish.

The first act of the film is very gloomy. It’s green, and it’s soft colours. And then the [magical] flower comes, and it’s a bit black. Then, everything goes into darkness, because that’s when we used a lot of the night shots: for the second and the third act. [Late in the film], fire was the most important thing. This fire would be the only colourful element of the scenery.

7R: How did you actually achieve that transformation in the dark room, when the girls become boys?

Alexandra Therese-Keining: There are a lot of special effects in those shots. It was extremely difficult for those kids who had never acted. They’d never been in a film, and then come special effects where the face and the body are transforming. It took forever. It took six hours of them standing exactly still in the same positions. It was really exciting.

We used a steady operation, a kind of motion controlled machine. It’s quite expensive, and it takes, like I said, forever to achieve that effect. You have to do it over and over again to get it exactly right, for the faces to blend. It was also harder because the room was dark, and it’s harder for cameras to find the lighting. It was really important that each transformation was different from the others.

7R: There are two really exquisite scenes in the water, one near the beginning with Kim and Momo, and then one later with Kim and Tony. What was the process for developing those scenes?

Alexandra Therese-Keining: I’m so fascinated by scenes underwater, that element, and the metaphors. In Greek mythology, water is a metaphor for change and transformation. Let’s just say, it’s two scenes that sort of mirror each other, but they have a completely different kind of connotation to them.

They’re kind of sensual, and it’s Kim’s experience of her first sensual feelings. It’s almost more sexual, I think, with Tony because they have this playful — you know, no-one really knows, they’re just messing around with each other. There’s a moment where Tony gets the whole tension and the whole seriousness of Kim. There’s the colours and the brightness of the first act, and then the complete opposite in the third.

Read more: Sonita and Sand Storm: when the patriarchy looks like your mother >>

Call Me by Your Name

Read Call Me by Your Name: A Special Issue, a collection of essays through which you can relive Luca Guadagnino’s swoon-worthy summer tale.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Read our ebook Portraits of resistance: The cinema of Céline Sciamma, the first book ever written about Sciamma.

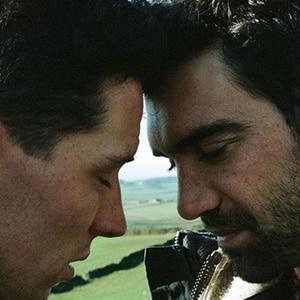

God’s Own Country

Read God’s Own Country: A Special Issue, the ultimate ebook companion to this gorgeous love story.