Suleiman Mountain director Elizaveta Stishova talks tragedy and farce, the film industry in Kyrgyzstan, and being a woman in rural Kyrgyzstan.

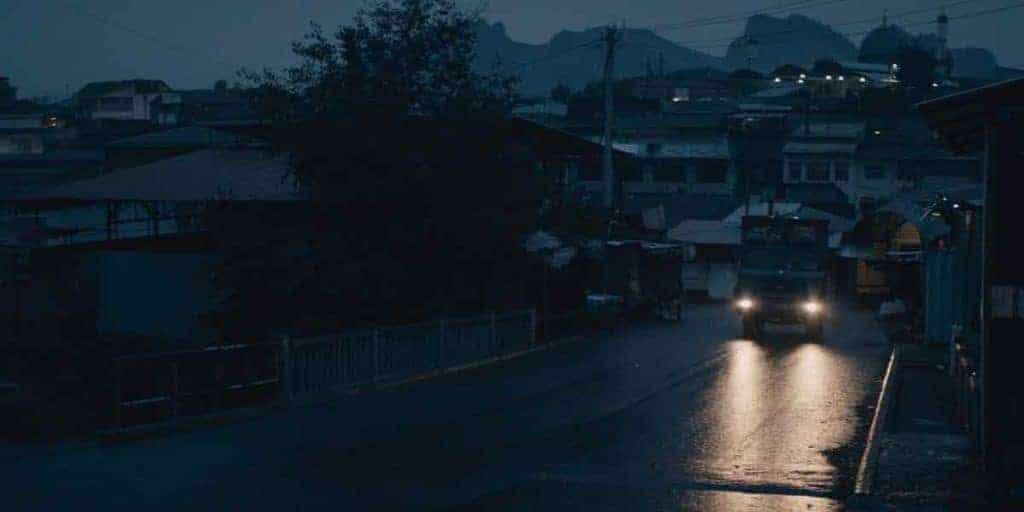

Set against the backdrop of Kyrgyzstan’s Takht-i-Suleiman mountain, Elizaveta Stishova’s impressive debut feature follows a family barely holding together. While the brash Karabas (Asset Imangaliev) struggles to make a living as a con man, his first wife desperately tries to distract him from his younger wife (Turgunai Erkinbekova) by getting him a son: she steals an orphan.

Poor and living in a truck, the troupe goes through happiness and heartbreak as Karabas’ selfishness and foolish ideas inevitably brings disappointment and pain upon the entire family, until a bittersweet finale.

With astonishing performances and a script full of ups and downs, Suleiman Mountain is a wildly entertaining ride — a tragi-comedy with endless compassion for all its characters, good and bad.

The Seventh Row interviewed Russian director Elizaveta Stishova about tragedy and farce, the film industry in Kyrgyzstan, and being a woman in rural Kyrgyzstan.

Seventh Row (7R): How did you get the idea for Suleiman Mountain?

Elizaveta Stishova: We were shooting a short film in Kyrgyzstan, and we saw a little boy and his mother. She was looking for him all day, and she couldn’t find him. We thought this could be an idea for a film: a mother searching for her son within that landscape with those huge mountains.

We went back home, then I came back to that idea. I was interested in this mother-son relationship in that setting. When we started working on it, it was a different story. It was really tragic and sad, and I didn’t think I could manage to realise that. I didn’t want to, anyway. So we went more towards what I call a tragi-comedy. But no one calls it that. Everyone says it’s a drama!

7R: Why did you want to insert those elements of comedy?

Elizaveta Stishova: Because these people from Kyrgyzstan are very funny. They are always joking. Even when someone has died, they make jokes.

They have this sense of humour between tragedy and comedy all the time, because they’re used to the situation they live in — poverty. So I wanted to show that attitude.

I didn’t want the film to be just a sad story. I wanted it to be fun, as well. Because I know them a lot, and I like that about them. I wanted to do them justice.

7R: The performances from everybody in Suleiman Mountain are really striking. All the actors manage the transition from comedy to drama very well. Are they professionals?

Elizaveta Stishova: The young boy, Daniel Daiyrbekov, is not a professional actor. And for Turgunai Erkinbekova [who plays the youngest wife in the film], this was only her second film.

The older wife is played by a professional actor [Perizat Ermanbetova], but she had been working as a makeup artist for about two or three years when I cast her. Nobody was casting her in movies. I was really surprised, because I like her a lot. She’s very smart and very professional.

Asset Imangaliev [who plays the father Karabas] is a star in Kazakhstan. He’s in all the historical movies made there.

7R: The older wife in the film is very strong, but she also always wants to please her husband, who is kind of horrible to her. Why this dynamic?

Elizaveta Stishova: Both in Kyrgyzstan and in Russia, the man is the main person of the family, and the women are alone. We have more women than men in Russia — same in Kyrgyzstan — and there is a point where you need to get a man in order to ‘be’ someone. That’s why, in the film, the first wife and his new, younger girlfriend, kind of fight for the guy.

But I was actually more interested in the husband than in the women. The movie focuses on him, in the end. I was curious about the change that occurs in him, throughout the movie, with the return of his son — all the consequences this has on his life. I understand what is going on with the women: they’re trying to get him interested. They don’t have a choice. But him, he has a chance to change.

7R: The film plays with the expectations of the viewer: every time something positive happens, something negative immediately follows, but in a completely unpredictable way. How did you write the film?

Elizaveta Stishova: I worked a long time on the script. My script writer, Alisa Khmelnitskaya, worked with me for three years on the story. Then, my director of photography (DOP), Tudor Vladimir Panduru [also DOP on Cristian Mungiu’s Graduation], came on board, and we changed the script some more, because he’s also a scriptwriter. He understood the film from the inside of the story: from the writing stage, to the shoot, and to the editing. I hadn’t worked with a DOP like that before. In Russia, DOPs just shoot beautiful landscapes — they don’t really care about what is going in the story. But he did, and that helped us a lot.

Then, Alisa came to the shoot, and we also rewrote some things then — the dialogue, etc. It brought more life to the film. We worked three years in advance, and we were again working on the script while making the movie. It was a very collaborative process.

7R: Why did you want to talk about the story of this boy who has disappeared? Is it true that you need to have a son for your husband to like you?

Elizaveta Stishova: Yes. There is this perception that if you don’t have a son, you are nothing. Even if you have five or six daughters. You must have a son. If you are married, have five girls and can’t have any more children, it is accepted for your husband to go have a son with another woman. A boy is like a ‘real’ child. Girls, they go away when they get married, while the boys stay and work.

We have this tradition where the youngest boy is the owner of the house, stays with his parents, and takes care of them until they die. He brings his wife to the house. Many girls don’t want to marry the youngest boy of a family, because doing so means leaving their own family. This tradition isn’t really in place in the city anymore, but in some regions of the Kyrgyz countryside, it still is.

7R: What’s the film industry like in Kyrgyzstan?

Elizaveta Stishova: They don’t have much money. They struggle, but they do release about a hundred films a year because they make very low budgets films. They can shoot a lot that way. And they’re fanatics about cinema. They love it.

That comes from the influence of the Soviet times, when Jewish directors kicked out of Russia came to Kyrgyzstan and built the cinema institute. Many Kyrgyzstani remember them. They inherit this love of cinema from them, to this day. It’s very nice to work with a team that come from there: they’re really passionate about cinema.