We interview director Francis Lee talks about the technical aspects of making his first feature, from sound to camera movement to editing. This is is an excerpt from our ebook God’s Own Country: A Special Issue, which is available for purchase here.

Yesterday, God’s Own Country dominated the British Independent Film Awards with 12 nominations: Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay for Francis Lee, Best Actor for both Josh O’Connor and Alec Secareanu, Best Sound, and more. It is one of the best films of the last year and certainly one of the most impressive directorial debuts. Here is part two of Seventh Row’s exclusive interview with Francis Lee where he talks about the technical aspects of making his first feature, from sound design to camera movement to the editing process.

Seventh Row (7R): The setting is such a crucial part of the film. Had you already found the location when you wrote the script?

Francis Lee: I wrote the script imagining it on my dad’s farm because I was trying to be pragmatic. I had no producers, no money, nothing. I thought, “Well, I could just shoot it there. It’ll be cheap.” But after shooting two shorts on dad’s farm, I thought I can’t put him through that again. It’s just too much.

Then, it became about trying to find the farm that had all those elements in it. We did find that farm which was incredible and perfect and no longer exists. It’s gone. He sold it. They’re converting the barn into a house, and the farmhouse is going to be all done up. They sold it last summer. Even the pub has been gentrified. That’s not the same. It’s been just over a year since we shot it. Those places don’t exist anymore.

7R: In the beginning of the film, there are all these abrupt changes between a quiet scene, and a quick, hard cut to the next scene which has really loud sound.

Francis Lee: That was very intentional. The sound was so important to me, and so carefully crafted. I wanted, in a sense, to keep being brought back to the reality of the world, the situation, the noise. Rather than having it be very quiet, seductive, I didn’t want people to get cozy at any point. The noises I think that you’re referring to are mechanical, right?

7R: Yes, like the sound of the heifer on the ramp getting onto the trailer and the gate.

Francis Lee: Yes. I wanted to undercut that natural world and the natural sounds with man-made sounds, or mechanical sounds. There’s also one of the quad bike. I ranked those up in volume, with another hard cut and a hard sound. It was always to undercut the rural, pastoral, “Oh this could be nice” world.

To read the rest of the interview with director Francis Lee, purchase a copy of the ebook God’s Own Country: A Special Issue here.

[wcm_restrict]

Seventh Row: Can you tell me a bit more about the sound?

Francis Lee: Because I’ve got incredibly sensitive hearing, I wanted to hear the film in the way in which I hear. We recorded all the natural sound. I hate ADR. I hate anything that isn’t recorded at source. On top of that, I got the sound designer to go to every location we went to and take hours of atmospheres when everyone else had gone. He went around and got specific doors in the house, the noise of the handle turning, or the noise of the door shutting, or the window open, the window closed, hundreds of different wind sounds from different places — a gust, or a light breeze.

When we started to edit, Chris and I, we knew we wanted to work with the sound at the same time as the picture. I think, usually, they do the sound after the picture. We knew fairly early on that we didn’t want to use a musical soundtrack. The wind, mainly, was going to be the backdrop, the soundscape.

Each wind sound would represent something else, and then we would layer them. Gheorghe has a very specific wind sound. When he arrives, he brings that. We first hear it in the caravan. It’s there at the shelter at the moor. Once he’s left, and Johnny’s on his own, the wind is there to remind him, very subtly, of Gheorghe. I saw it like a Greek chorus going, “Oh, where’s Gheorghe, Johnny?” — questioning him, pushing him.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘The wind is there to remind him, very subtly, of Gheorghe. I saw it like a Greek chorus.'” quote=”‘The wind is there to remind him, very subtly, of Gheorghe. I saw it like a Greek chorus.'”]

We built all these wind sounds. You’d have five or ten minutes of “gusty” and then “wind through pilons”, those are the electric wires. We could also keep underpinning the idea that this is a natural world, but that man was trying to control it.

The birds are very significant. They’re all native to the specific area where we shot. But they all act as a metaphor. The curlues, up when they’re on the moor doing the lambing, in some kind of mythology, they’re a harbinger of spring, of change, of renewal, of new life. They start becoming quite present when their relationship develops. Swallows are migrating birds, and they mate for life. They come in when the boys are together in bed in the farmhouse, and then they’re there again, once Gheorghe has left, to remind Johnny. Once he gets to the potato farm, there are the swallows again.

For the campfire, there were lots of different campfire sounds. We had roaring. We had quiet. We had crackly. It was all to underpin and reflect the emotion of what was going on.

I had a nightmare trying to explain to people how important this was, that the lamb sounds had to be correct. There’s a specific lamb sound that it makes when it’s calling to its mother that is different than when it’s just skipping around. When Gheorghe revives that stillborn lamb, it makes that sound it would make to its mother, but it’s making it to Gheorghe because he’s very maternal, or paternal.

Hospital scenes have always got beeping and stuff like that. I knew I didn’t want that. I knew I wanted this place that was horribly silent. I plotted in some people laughing down the corridor, just to make sure we knew that life was still going on, and other people were getting on with their lives. But for these people, everything had stopped.

7R: How did you think about how and when to move the camera?

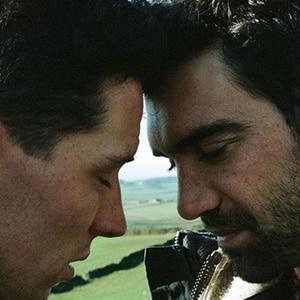

Francis Lee: Joshua James Richards, the brilliant cinematographer, and myself worked incredibly hard on how the camera moves. We had very strict rules about it. It was very important to limit what we would do and how we would depict it. One of the ideas was from the beginning, you only ever see Johnny in a single. You never see him in a frame with anyone else. When Gheorghe arrives, you see them in singles. And then, very slowly, the camera moves between them. Then, you start to see them in the frame together. It was that idea of isolating them by using the camera, by using the framing.

One of the things I discovered by working with Joshua was I love shooting quickly. I like one, maybe two, takes in every setup. Poor Joshua operated so he was exhausted, because obviously, he’s holding this bloody camera, and I’m going like, “Let’s shoot the whole scene.” He would then rove with the camera.

He’s such an artist that it worked so beautifully. I love that idea of passing the emotion backwards and forwards between the characters and connecting them, and us connecting with that relationship, as a viewer.

7R: There are a lot of really interesting shots of hands in the film. When they go off to tend to the sheep on the moor, in the shelter, when Gheorghe comes in at night, there’s a closeup on Johnny’s hand in the hay. When he’s at the hospital, Gheorghe comforts Johnny with his finger on his hand, and Johnny then uses the same gesture with his father.

Francis Lee: I’m obsessed with hands. I love hands. I think hands tell us an awful lot of people, what they look like but also the tension. I’m a big fan of where tension comes out in people. Some people wobble their leg or fiddle with something. I fiddle with my beard.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘They look like they’re hands that have been passed down for generations.'” quote=”‘They look like they’re hands that have been passed down for generations.'”]

When I first met Josh, the thing that really struck me massively were his hands. He’s got massive hands. They look like they’ve worked, and they haven’t. They look like they’re hands that have been passed down for generations. In the script, I think I described Johnny as having hands like meat shovels.

7R: Everything Johnny does is quick, hurried. His idea of taking a break for himself is getting drunk or having very quick sex. Then you have Gheorghe who is much calmer and takes his time with things. Gheorghe has this influence over Johnny and is changing his behaviour.

Francis Lee: Both of those characters were almost like mirror images. Gheorghe was always going to be this kind of calm but firm type of character. He was going to get pleasure out of things. He doesn’t just believe in function, whereas Johnny is just function: he has sex, so he just gets off. That’s it. Really little pleasure in that. He gets so drunk he throws up. There’s no pleasure in that. Everything is locked. He eats incredibly quickly.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘If you can be happy, you can be sad. Someone can take that away.’ – Francis Lee ” quote=”‘If you can be happy, you can be sad. Someone can take that away.’ – Francis Lee”]

It’s all of that that Gheorghe unlocks. It’s about saying to somebody, “It’s okay to enjoy things, to allow yourself to enjoy things.” I think Johnny’s way is not that because that involves sometimes emotion, like happiness, and that can be dangerous. Because if you can be happy, you can be sad. Someone can take that away.

7R: In Johnny’s room, there’s clothing all over the floor. It’s like what you’d expect from a 16-year-old who doesn’t clean up after himself.

Francis Lee: That’s typical Johnny, I think. One of the things we did in the prep was I took the family to the house, the location, and showed them round. With [Josh], I went, “OK, this is Johnny’s bedroom. Where would he have the bed? Why would he have it there? What does he have on the wall? What’s on the floor? What other clothes does he have that we don’t see him in? What’s in the cupboard? What’s in the drawer?”

Josh had quite a hand in creating that space. We worked out that his bed was there because it was the warmest place in his room. He’d signed all this graffiti on the wall. I don’t think you see it in the film, but it’s there. We mention that when he was 14, or something, he was writing on the wall.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Josh had quite a hand in creating that space. We worked out his bed was in the warmest place in his room.'” quote=”‘Josh had quite a hand in creating that space. We worked out his bed was in the warmest place in his room.'”]

It’s also because he doesn’t think about things, so he just takes off clothes and leaves them on the floor. And his grandma cleans up after him, clearly. Dierdre, the grandma, is very much the idea I had of a very, very loving person, but not demonstrative. She shows how much she cares by her actions, not by what she says. He comes in, and he sits down for his dinner, and she gets up and goes and gets it and comes and puts it in front of him. She’s making sure he’s getting what he needs to keep that farm going.

7R: At the end of the film, Johnny leaves the farm for the first time to go find Gheorghe. Since all outward journeys are inward journeys, how did you think about this?

Francis Lee: For me, there was such a beautiful vulnerability about that character and the way in which Josh portrayed him. He really got that.

I’m a huge fan of actors and their skill. I think you can get these authentic, truthful performances without having to street cast. It’s just about the way you work, stripping some things away and building other things up.

When I was writing it, I loved the idea that he’d never been anywhere. He’d never left that hillside, really. For me, it starts building when he’s getting ready. You see him in the kitchen with his grandma, and he’s got a jacket on that you’ve never seen before because it’s obviously his best jacket. That, to me, breaks my heart, because he’s like “going to put my best jacket on to meet him.”

When he’s on that coach, Josh conveys such vulnerability. Johnny is totally out of his comfort zone, totally lost, but he’s still doing it. He’s still going to try. There’s something in that, him trying so hard, that I wanted to convey.

Read the rest of our ebook on God’s Own Country here >>

Read more about great queer cinema like God’s Own Country…

Call Me by Your Name

Read Call Me by Your Name: A Special Issue, a collection of essays through which you can relive Luca Guadagnino’s swoon-worthy summer tale.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Read our ebook Portraits of resistance: The cinema of Céline Sciamma, the first book ever written about Sciamma.

God’s Own Country

Read God’s Own Country: A Special Issue, the ultimate ebook companion to this gorgeous love story.

Sound tends to obsess so many of the best directors. Cristian Mungiu told us about how he records sound on set, even getting his actors to do an entire scene without the dialogue, in Graduation. Joshua Oppenheimer told us about how he used sound to turn his documentary The Look of Silence into a magic realist film. And Andrew Haigh talked about using sound to create a sense of unease in 45 Years.

[/wcm_restrict]