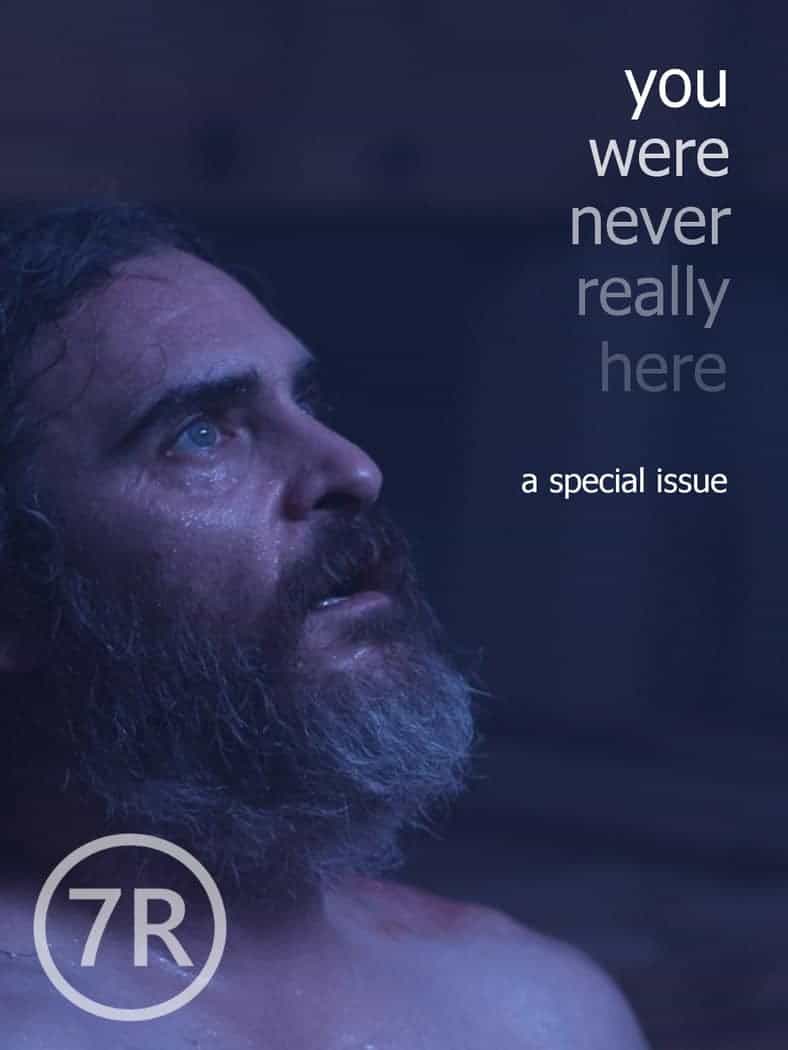

In this interview, Lynne Ramsay talks subverting hitman archetypes with gentleness, humour, and beauty. Ramsay discusses collaborating with cinematographer Tom Townsend, Editor Joe Bini, and Sound Designer Paul Davies to craft a dense and complex film in record time. This is an excerpt from our ebook You Were Never Really Here: A Special Issue which can be purchased here.

Lynne Ramsay’s fourth feature, You Were Never Really Here, is a brutal thriller that breaks down genre boundaries. The premise — PTSD-stricken hitman Joe (Joaquin Phoenix) is tasked with saving a young girl from sex traffickers — probably sounds familiar. Narratives of male saviours rescuing female innocents are baked into pop culture: if you’ve seen Taxi Driver, Taken, or Drive, then you know how these things go. But Ramsay’s film sets itself apart: amidst the violence is gentleness, beauty, and a delicacy and variety of style.

At the Glasgow Film Festival, I talked to Ramsay about making a subversive film, depicting violence, and her approach to visual storytelling.

Seventh Row: Joe is a very stoic and emotionally repressed character, on the surface, but you subvert that common characterisation by revealing gentleness underneath. How did you approach giving us glimpses of his softer side?

Lynne Ramsay: Casting Joaquin Phoenix. I felt he would bring a vulnerability. Everything we try to do is to humanise [Joe], to not go down that route of the cliché of these kinds of movies — but at the same time, make a really compelling and propulsive movie. For me, it was about bringing that character to life by showing his flaws, his vulnerabilities, his humour, his breakdown…

Seventh Row: It’s such a brutal film, and yet there are moments of comedy — especially between Joe and his mother, like when he teases her by screeching the Psycho theme, or when he’s playing around with a knife while waiting for her to leave the bathroom. Why was it important to include comedic moments?

Lynne Ramsay: We didn’t want it to be a one-note thing. [Joe and his mother] have quite a crazy relationship, but it’s really beautiful and tender. She drives him nuts, sometimes, so humour gives a kind of authenticity. We’re always trying to play each take showing some other aspect of the character, so that they feel well rounded.

[Joe]’s a mess. He’s not a white knight that comes in and rescues the girl. It’s not that at all. It turns on its head. I changed the whole fourth reel — it’s completely different in the book. We were looking at Joe’s impotence, in the end: the fact that he fails, but also the fact that he comes back to life, in some way, through the girl.

7R: You juxtapose upbeat music with graphic violence a lot, like the scene where we see Joe’s killing spree through CCTV footage. That scene starts with romantic music and the promise of violence, which led me to expect some kind of cathartic thrill from the contrast, like we’ve seen in other genre films. But you don’t do that at all. The music jumps about in time and volume, so it’s really uncomfortable to watch. You feel trapped in Joe’s warped mind. How did you work with your editor to make us share his fractured headspace?

LR: That sequence was meant to be filmed over three days — and then we realised we had one day to shoot it. So I had to think about, psychologically, where he’s at. I thought, “What if we do it in a really mechanical way? What if we do it in a way that feels like a machine?” Somehow, that led to the form taking shape. But it was quite a bold thing to do, because if it didn’t work, we didn’t get a second shot at it.

I don’t even like violence in films! [Stunt choreographers] always want to do this balletic stuff from working in a lot of TV. But [in reality], you hit someone and they go down, you know? Also, I was watching a lot of stuff on YouTube where you were seeing slightly out of frame violence from surveillance cameras and stuff like that. It felt like what you didn’t see was somewhat more violent — without that explicit, glamorous, ‘this is cool’ kind of thing. But also, it was important that the film felt exciting to watch.

There was a lot of experimentation with the sound design and the music, which was the part that I really loved. Sound can bring you into the film’s world in a subconscious way — often in a more powerful way than the image does.

The rest of the article is available in the ebook You Were Never Really Here: A Special Issue which can be purchased here.