Placing The Miseducation of Cameron Post and Madeline’s Madeline side by side, it seems like DP Ashley Connor can do anything. Read more interviews with cinematographers in our Behind the Lens series.

Faces are the camera’s primary fascination in The Miseducation of Cameron Post. DP Ashley Connor observes the trauma inflicted on kids at gay conversion therapy camp by patiently capturing their fear, defiance, and self-hatred. Connor is one of the most exciting up-and-coming DPs because, despite her ability to create immensely beautiful images, her work is always in service of the story she’s telling. Her visual choices heighten whatever Cameron (Chloë Grace Moretz) is feeling — from loneliness to belonging — in the subtlest, craftiest of ways.

Cameron Post isn’t Connor’s only high profile work this year. Her longstanding collaboration with experimental filmmaker Josephine Decker (Butter on the Latch, Thou Wast Mild and Lovely, Flames) has now amounted to their biggest arthouse success yet, Madeline’s Madeline. Exploring the unpredictable mind of a mentally ill teen as she takes part in a drama production, this was much more of an obvious showcase for visual flair. Connor goes wild with her camera, pushing the limits of visual storytelling in an attempt to immerse us in Madeline’s unique mind. It’s worlds away from Cameron Post; placing both films side by side, it seems like Connor can do anything.

I talked to Connor about making Cameron Post, subjectivity in both of these very different films, and what her roots in low-budget indie cinema have taught her.

Shooting indie films

Seventh Row (7R): You’ve worked largely in low-budget indies. How do you make something look cinematic and artful with relatively few resources?

Ashley Connor: I don’t try to do things that we can’t afford. I’d rather view the limitations as a positive rather than being upset that I can’t have every nice piece of gear. It’s about embracing the budget and making the most of it. That’s exciting to me. Having a load of budget where you can have anything stops you from being your most creative. I guess, alternatively, you could say that then you have any tools at your disposal, but something about all the limitations frees my mind to be more open.

The Miseducation of Cameron Post

Preparing for the shoot

7R: What initial story conversations did you have with director Desiree Akhavan about The Miseducation of Cameron Post?

Ashley Connor: We talked about growing up. Our conversations were centred around what kind of movie we would have wanted to see when we were teenage girls: what would that look like and how would that feel. What was necessary to show in a film like that — to show women that there’s a different path? A lot of our conversations were centred around approaching the sex scenes and what that meant to us.

It was a very open conversation. We talked a lot about French cinema. Desiree has an extensive knowledge of film.

7R: Were you involved in the location scouting?

Ashley Connor: I shot three movies in a row that year, and on my off days, I would be prepping the next film. On off days on Madeline’s Madeline, I would go out and location scout for Cameron Post.

At a certain point in our conversations, we realised that pretending that the movie was set in Montana was going to feel very false. So we opened up the idea that this could be anywhere in America. The location doesn’t really matter. It was just about finding the right space. We saw so many different ski resorts, so many different abandoned schools. A lot of gay conversion therapy spaces are alternative spaces, just whatever they can get to house these children. The Austrian resort that we shot in is very old school. I think it was made in the ‘40s, or maybe in the ‘20s.

Designing the film’s aesthetic

7R: What overall aesthetic did you devise together?

Ashley Connor: The movie’s fun, but it never gets that fun, because the characters are going through a deeply traumatic experience. We wanted the visuals to reflect that. The paletting of the movie is very beige. We’re not doing fancy steadicam moves or big fun dolly movies. It’s pretty locked off. It’s really about the portraiture of these teens, whom you really get to empathise with throughout the film.

7R: Did the film being a period piece — it’s set in the ‘90s — affect your shooting style?

Ashley Connor: We were all on the same page that, although this is a period film, it could really be taking place today. While we wanted to see the period, we didn’t want it to feel too vintage. We were striking a balance between what could speak to teens today while still bringing a flare of the ‘90s into it.

7R: How did you choose the 1.85:1 aspect ratio?

Ashley Connor: To do something like anamorphic, a movie has to really convince me of that. I think that it’s a default tool for a lot of DPs if they want to make something quote unquote cinematic. For me, this film felt so personal: so much about the space and so much about connecting to these kids. We needed to have the camera close to them, and to favour a lens and an aspect ratio where portraiture could be at the forefront.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘We needed to have the camera close to them, and to favour a lens and an aspect ratio where portraiture could be at the forefront.'” quote=”‘We needed to have the camera close to them, and to favour a lens and an aspect ratio where portraiture could be at the forefront.'”]

Ashley Connor on depicting Cameron’s perspective

7R: The film is so patient, sensitive, and empathetic to Cameron’s point of view. How did you approach shooting the film to involve us in her subjective experience?

Ashley Connor: When I read the script, what I really responded to was the fact that Cameron is not a stereotypical character. Queer kids have been fed this narrative of the tortured soul who wants to kill themself because they’re gay. That’s just not who Cameron was. From start to finish, she’s pretty much like, “This is who I am. There are all these external forces yelling at me, and that’s making me question myself.” But for the most part, I found it really refreshing to see a young female character who wasn’t questioning themselves. They kind of knew what they were. That gave her an inherent strength that a lot of women’s stories aren’t given.

We wanted Cameron to be powerful, and we wanted the images to reflect that. Desiree really wanted it to always be on the kids’ level. Whenever you’re watching them, you feel like you’re part of the disciple group. We never shot from crazy high or low angles. The way the lens views the world is like their great equalizer. And that felt important for being on Cameron’s team. There’s no drone shots. It feels very personal.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘I found it really refreshing to see a young female character who wasn’t questioning themselves. That gave Cameron an inherent strength that a lot of women’s stories aren’t given.” quote=”‘I found it really refreshing to see a young female character who wasn’t questioning themselves. That gave Cameron an inherent strength that a lot of women’s stories aren’t given.”]

7R: Cameron is an isolated character who finds friendship and community in the camp. How did you shoot her in moments when she feels isolated as opposed to when she feels part of a group?

Ashley Connor: A lot of that had to do with the production design, costume design, and the story that we’re telling through colour. When Cameron, Adam [(Forrest Goodluck)], and Jane [(Sasha Lane)] go out together, colour comes more into their world.

It was also about framing them together in the way that teenagers kind of lounge on each other. Capturing that intimacy that, as you get older, you lose some sense of. You don’t get as close to people. You’re not lounging all over everybody. We really wanted to capture that level of friendship that they build at this camp and how important touch is to them.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘We never shot from crazy high or low angles. The way the lens views the world is like their great equalizer.'” quote=”‘We never shot from crazy high or low angles. The way the lens views the world is like their great equalizer.'”]

Aesthetic challenges: group scenes, darkness, and more

7R: You have the really dialogue heavy group therapy scenes, as well. How did you make them engaging?

Ashley Connor: At the end of the day, The Miseducation of Cameron Post could have been the miseducation of any of these kids. We really wanted to honour that. We wanted you to love each and every one of the disciples at the camp. They’re not just background props. You feel empathy toward them.

It’s the same with [the camp leaders,] Rick [(John Gallagher Jr.)] and Lydia [(Jennifer Ehle)]. Even for those characters, we wanted there to be some sense of empathy toward them, because it’s just such a complicated situation. Maybe less so Lydia, but Rick is a very tragic figure, in my mind.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘It was also about framing them together in the way that teenagers kind of lounge on each other.'” quote=”‘It was also about framing them together in the way that teenagers kind of lounge on each other.'”]

7R: There’s a really striking use of shadow in the film. In a lot of key scenes, especially the sex scenes, the characters are shrouded in darkness.

Ashley Connor: Desiree really wanted the spaces to feel like they would really feel. We were pushing the image to the point of breaking in low light. I would be adding more lights, but she would say, “It doesn’t feel like kids hooking up in the middle of the night. It has to feel darker.”

I also feel like it conveys desire in a very literal and subconscious way. You desire to see more and you can’t.

Also, for the sex scenes, we really wanted to avoid the Blue is the Warmest Color sort of objectification of these women.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘We wanted you to love each and every one of the disciples at the camp. They’re not just background props. You feel empathy toward them.'” quote=”‘We wanted you to love each and every one of the disciples at the camp. They’re not just background props. You feel empathy toward them.'”]

Depicting the characters’ environments

7R: The film is about these characters who are constricted by their environment. How did you approach shooting the film to reflect that, and in contrast, how did you shoot the moments when they find some kind of freedom?

Ashley Connor: The interiors should feel very institutional and reflect the prison-like environment that these kids are in. Then, for the exteriors, we really wanted to open it up. We wanted the frame to get wider. We wanted them to feel more free and a little bit looser.

Then, once we get to the final shot, that’s kind of our The Graduate moment. While we’re happy that the kids have escaped, at the end of the day, the reality is that their journey’s just beginning. Where are they going to stay? They don’t have a support system. It was about making you feel kind of elated but not too elated because you have to realise that these kids chose homelessness versus staying at God’s Promise. And that’s a pretty serious decision.

[click_to_tweet tweet=”‘I would be adding more lights, but Desiree would say, ‘It doesn’t feel like kids hooking up in the middle of the night. It has to feel darker.”” quote=”‘I would be adding more lights, but Desiree would say, ‘It doesn’t feel like kids hooking up in the middle of the night. It has to feel darker.””]

Madeline’s Madeline

7R: Madeline’s Madeline is a much more intensely subjective film. How did you approach really understanding what it’s like inside Madeline’s head and conveying that visually?

Ashley Connor: We knew that Madeline was an unstable character, and we knew that, as the movie went on, the reality that you’re presented with is not necessarily the actual reality. I wanted to really degrade the image and make it bleed and melt. It was about creating a new way of seeing.

Josephine’s very playful and lets people do what they want. For me, it was about inhabiting this young girl’s mind while she’s lost her hold on what reality is. And actually, as Madeline’s Madeline goes along, it goes from extremely abstract to more literal, which was also a choice. The obvious choice would be to have the visuals gets crazier and crazier and looser and looser, but instead, we wanted them to become more structured — except your relationship to them is on shaky ground.

Shooting in New York

7R: Madeline’s Madeline is one of several of your films to be set and shot in New York. There’s such a rich history of cinema set in New York. Is it difficult to avoid that aesthetic influence, even subconsciously?

Ashley Connor: I didn’t end up shooting an actual New York feature until my fourth or fifth feature. So, by that point, I was really hungry to shoot New York. I’d travelled around, shot movies in the South, shot them in other cities, and so by the time I got to New York, I wanted to do it justice in the way that feels like my New York. Sure, there’s some iconography involved. But for the most part, I’m interested in showing a different kind of New York than just some of the obvious indicators. For Madeline, you might know it’s in New York, since they talk about it, but it’s not really that grounded here.

7R: Do you tend to watch other films that were shot in the place you’re filming?

Ashley Connor: No, not really. Once I get into shooting, it’s really difficult for me to watch great movies. I tend to watch mindless TV instead. I find watching a really good movie set in a similar place while you’re trying to film there makes you feel the weight of that influence a little too much.

Read more interviews with cinematographers in our Behind the Lens series >>

Love The Miseducation of Cameron Post? Keep reading about great queer cinema…

Call Me by Your Name

Read Call Me by Your Name: A Special Issue, a collection of essays through which you can relive Luca Guadagnino’s swoon-worthy summer tale.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Read our ebook Portraits of resistance: The cinema of Céline Sciamma, the first book ever written about Sciamma.

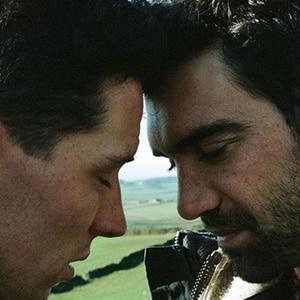

God’s Own Country

Read God’s Own Country: A Special Issue, the ultimate ebook companion to this gorgeous love story.