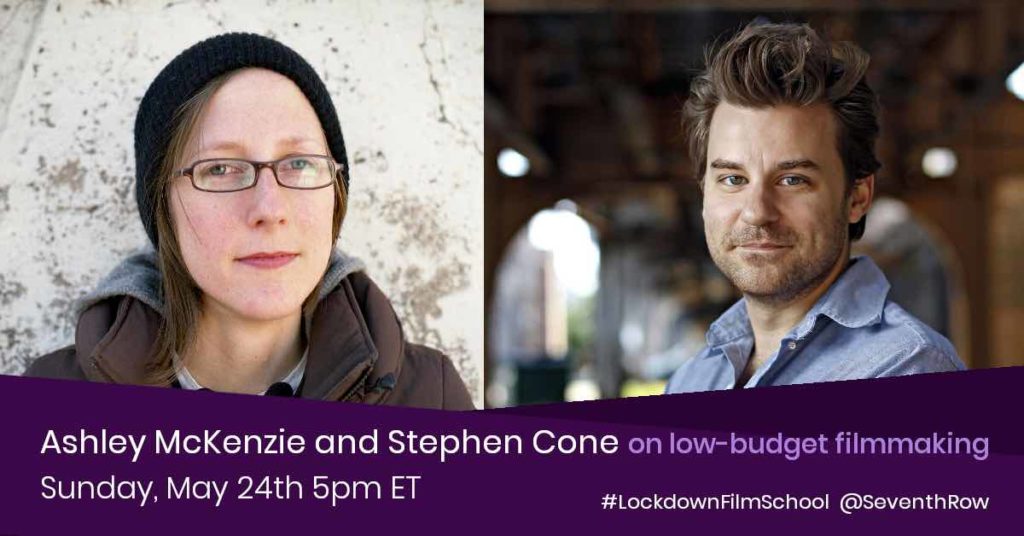

Ashley McKenzie’s 2016 film Werewolf was one of the most exciting directorial debuts of the 2010s. As McKenzie finishes her second feature during lockdown, catch up with this film about drug addiction and dependent relationships in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Read our interview with McKenzie. Watch our livestream with McKenzie and Stephen Cone.

Shot and set in writer-director Ashley McKenzie’s home of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada, Werewolf is a geographically and culturally specific coming-of-age story about drug addiction and dependent relationships. We follow couple Blaise (Andrew Gillis) and 19-year-old Nessa (Bhreagh MacNeil) as they push a lawnmower around and knock on doors day in day out, trying to get paid to tend to the front yards of locals. Their rusty old lawnmower is all that’s keeping them afloat as they persist through a trying methadone programme at a local clinic. The film was inspired by the very real drug problem in Cape Breton and McKenzie based the characters on a couple of “lawnmower crackheads” (as the locals called them) whom she spotted going door to door one day in her hometown.

The film is more about recovery than it is about addiction, and more than that, it’s about the tension between a couple who is trying to get clean together. While Blaise is the more loud and talkative of the pair, the younger Nessa is slowly revealed to be our protagonist (or at least the character with which we can most easily align our sympathies).

Nessa rarely speaks because Blaise takes it upon himself to speak for her. She’s a young woman without a voice, but she’s also dedicated to making a better life for herself and carrying out the methadone programme. Throughout the film, she makes leaps and bounds, even securing herself a job at a local ice cream shop. The film’s central conflict is the decision she realises she must make: should she prioritise her own recovery and future, or should she prioritise Blaise?

Meanwhile, Blaise succumbs to his demons time and time again. While we, as an audience, may dislike the disempowering way he treats Nessa, McKenzie also asks us to question why he has a harder time getting clean. He’s older, so he’s faced more roadblocks in his life, and it’s also implied that he has a child he’s not allowed to see. For Blaise, life has been a series of disappointments. Without the money or resources to pull himself out of bad situations, he’s ended up a rootless drug addict with nobody to depend on but Nessa.

Werewolf is a gripping film that avoids poverty porn by asking real moral and personal questions while also revealing all the systemic processes Blaise and Nessa are at the mercy of, that either aid or hamper them. McKenzie’s camera doesn’t feel exploitative either. She has an off-the-cuff, documentary-like approach that allows the audience to observe the characters’ emotions without feeling too invasive. She might hold on a small detail of an actor’s face for most of a scene or find a simple composition that allows the characters room to breathe and interact with each other in the same frame.

Read our interview with McKenzie about how she conceived and crafted Werewolf >>

Watch our livestream with McKenzie and Stephen Cone >>