Writer-director Arsalan Amiri and co-writer Ida Panahandeh discuss their first foray into genre territory, Zalava, which won prizes at the Venice International Film Festival.

Click here to find all of our TIFF 2021 coverage and sign up to our TIFF newsletter.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

In a remote town populated by, as the film calls them, “gypsies”, in northern Iran, a demon has purportedly possessed a girl, causing her to jump to her death. It’s 1978, just before the Iranian revolution, and the townspeople are worried that the demon will jump into someone else’s body. An exorcist arrives (Pouria Rahimisam), especially conspicuous in his western-style suit. He goes into the house where the demon is supposed to be, and comes out with a sealed glass jar which he claims now contains the demon.

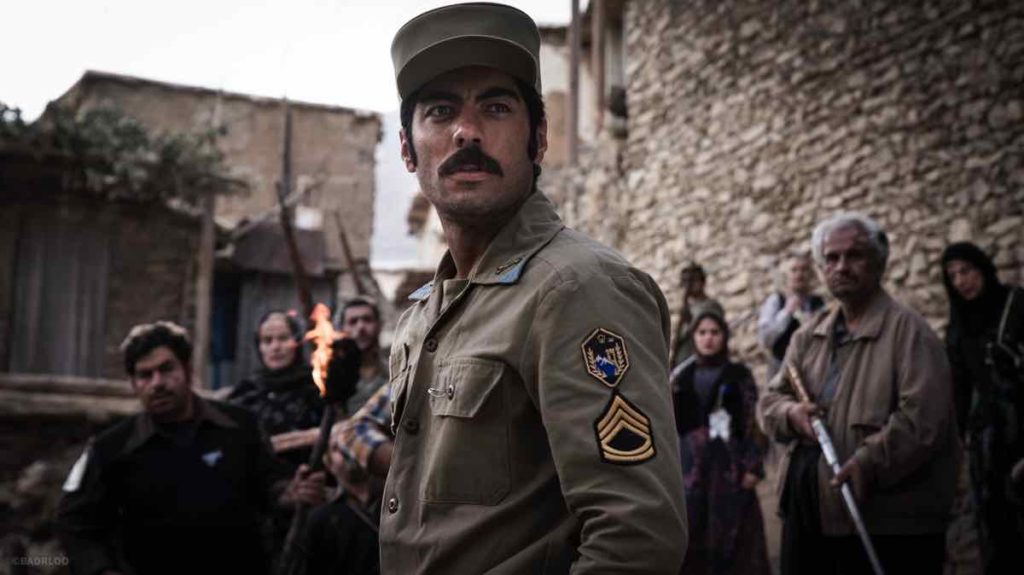

The townspeople rejoice; the local sheriff (Navid Pourfaraj) thinks it’s bullshit. His solution is to arrest the exorcist, but there are unintended consequences. Will removing this beloved potential charlatan incite a riot? Should he let the exorcist be to calm the townspeople or should he avoid giving so much power to someone who could misuse it? These are the central questions of Arasalan Amiri’s directorial debut, Zalava, a horror film that is firmly rooted in reality, with a touch of black comedy.

The early parts of the film have us, and the characters, asking, is there really a demon in the jar? There’s some very funny business involving misplaced jars, nightmares, and potentially opening the right or the wrong jar. As the film develops, whether the demon is really in the jar becomes less important than whether people believe there is a demon in the jar, as superstitious mobs threaten to not only disrupt the peace but kill some locals.

“Superstitious people don’t just hurt themselves,” the sheriff opines to the local doctor he’s crushing on. “They are dangerous to everyone.” What follows are the consequences of the decisions and concessions he makes to try to prevent superstition from dominating; we’re left wondering whether he should have interfered at all. He’s outnumbered by the townspeople, and if they turn against him, he has little recourse to save himself.

Amiri, who co-wrote the screenplay with his wife of twenty years, Ida Panahandeh, and Tahmineh Bahramalian, got the idea for Zalava over a decade ago. But it’s been on the backburner as he helped Panahandeh get her own films as a director — among them Nahid (2015) and Titi (2020) — made, on which he has served as co-writer and editor. For Zalava, they swapped roles, still co-writing the film together, but with Panahandeh in the cutting room while Amiri went to set. As Panahandeh puts it, she stayed off set because “it’s impossible for a director to be on set and keep silent.”

For his first feature, Amiri cites influences as wide-ranging as Federico Fellini’s La Strada (1954), Vttorio de Sica’s Miracle in Milan (1951), Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972), the Coen Brothers, and of course, Abbas Kiarostami. His goal was to make, as he describes it, a ‘hybrid film’ that straddles the line between genre and realism. “This style maybe comes from my life. My father is Suni. My mother is Shiite, a different kind of Islamic religious group. These are two different ways of looking at and thinking about Islam.” Amiri wanted to set Zalava in a “gypsy” community because they exist everywhere in the world, which allowed him to tell a sort of parable about humanity.

Zalava had its world premiere at the Venice International Film Festival, where it won the Grand Prize of the Venice Film Critics’ Week and the FIPRESCI International Award. Before the film’s North American premiere in the Midnight Madness section of TIFF, I sat down via Zoom with Amiri and Panahandeh to discuss Zalava, collaborating on each other’s films, and merging genre filmmaking with realism.

Seventh Row (7R): What made you want to tell the story? Where did this idea come from?

Arsalan Amiri: The idea came from my father, who told me a story about one of our ancestors, who captured a kind of demon in Islamic cultures. He wanted the demon to do things for him, like a slave, like bring water from the river. This story was strange for me. But the way my father told this story, that he believed this fantastical story, was surprising to me. He was an educated man and an army officer, but he believed this strange story. This theme of belief was the starting point for me to write my first feature film.

7R: You two have collaborated on the screenplay for all of Ida’s films, and now, of course, you’ve collaborated on your first film, Arsalan. How do you two work together to write your screenplays?

Ida Panahandeh: We were students at film school. I was nineteen, and Arsalan was twenty two. Twenty years ago. First, we were classmates, then we fell in love, and we worked together.

Arsalan Amiri: I fell in love first, not we.

Ida Panahandeh: We started to work on short film projects, and then we decided to marry because it was a long, long time of working together. We got married. After five years of our marriage, we were working on TV movies, and this kind of stuff. We decided to work on our first feature film together, which was Nahid.

How we work together is not that easy. We discuss with each other and we fight. But we know each other very well. We’ve known each other for twenty years. We are very, very close to another person’s soul. I think this is why we always work together. And I have to say that I’m happy. I’m happy that he is a very, very good collaborator, a very, very good mate.

7R: Arsalan, you’ve been working as a writer and an editor on Ida’s films. What made you want this film to be your first feature as a director?

Arsalan Amiri: I wanted to make my first feature film for many years. I chose the directing course at the Art University of Tehran. My bachelor is in directing, and my master’s [from the University of Tehran] is in dramatic literature. I wanted to start as a director, but when I met Ida, Ida was eager to make films, and I helped Ida make films. Because of that, maybe my first feature film became delayed.

When we wanted to make Nahid, I had this idea. I had a plot of Zalava. Before Nahid, I wanted to make Zalava as a TV drama. But we thought together it would be better that we started to make Nahid, and then I would make Zalava. After Nahid, I wanted to start Zalava. Ida told me, “I want to start Israfil (2017).” I obeyed Ida again. After Israfil, Ida told me we have a good offer to travel to Japan and make a Japanese film [produced by Naomi Kawase]. It was wonderful for me. I obeyed again. Then, we started the Nikaidos’’ Fall (2019). Then, I wanted to start Zalava again. Again, Ida told me Titi is a good idea. We can make Titi then Zalava. Okay, I obey, and then finally, Ida accepted that we would start Zalava. I’m kidding, you know!

7R: You’ve talked about Zalava as being a hybrid between genre film and realism. How did you approach developing the aesthetic for that?

Ida Panahandeh: (Translating for Arsalan) Arsalan says: ”My DoP [NAME] and I are very big fans of both genre movies and arthouse movies. Before we started shooting, we watched all the things that I [was inspired by]. We decided how we can mix, for example, lighting and mise en scene.” Arsalan believes that this is a hybrid movie. I don’t know if it is or not, but he says it is.

Arsalan Amiri: The story showed us what we should do. The story has a kind of melodrama, a kind of horror, a kind of drama, a kind of thriller, and a kind of mystery. In collecting all of them, the film is a fantasy film. But we wanted to make a local, Iranian fantasy film, not a Hollywood fantasy film. Because of that, in lighting, mise en scene, decoupage, the acting, directing, clothes, and the colour of the film — all of them we want to remain on a line somewhere between a genre movie and an arthouse movie.

I think we are best, in Iranian Cinema, as social filmmakers. [Zalava is] inspired by Iranian social movies, a kind of realistic movie like [Iranian filmmaker Abbas] Kiarostami, genre movies, and our culture. Our experience with everyday life in Iran could help us to make a fantasy film with a realistic approach.

Ida Panahandeh: I think Zalava, in lighting and form, is a realistic film. For example, in the village, they don’t have electricity, because it’s 1979. So why they use these lamps and this kind of horror, black scenes, that’s because there is no electricity there. Everything comes from realism, not something that we wanted to make a genre movie. It’s not like that. Of course, we used some elements of horror movies, because Arsalan likes them. But as he said, realism is something that we have to put there and Arsalan had to emphasize this realism.

Arsalan Amiri: I control the amount of horror in the film. There should be a limit. I didn’t want to make a horror film. I wanted to make a kind of local horror film, with light horror and drama, to say some things, not only to scare people.

7R: Both Zalava and Titi had characters who the films refer to as “gypsies.” I don’t really know much, personally, about gypsies in Iran, but obviously, that’s something of interest to you. Can you talk a bit about why you wanted to tell those stories?

Ida Panahandeh: Even now, many Iranians don’t know that we have thousands of gypsies in Iran, and that they have lived here, I think, since a thousand years ago. They live mostly in the northern part of Iran. People in the north usually don’t treat gypsies very well. They think that they don’t have any special religion, don’t respect anything, and don’t believe in God.

Arsalan Amiri: I think everywhere in the world there is this behaviour towards gypsies.

Ida Panahandeh: They are anarchists. They are not well educated in Iran. They are not economically well off; they don’t have good lives. To make ends meet, they are drug dealers and these kinds of things. That is why they always live in the suburbs of big cities, and that’s why people don’t respect gypsies that much. I think that gypsies always have the strangest stories, which come from their history. They are very connected with nature, and that’s true of gypsies all over the world.

Twelve or thirteen years ago, we watched a very good documentary, Siva by Mehdi Moniri, about gypsies living in the north of Iran. We didn’t know that gypsies are living in Iran. Bahman Kiarostami, the son of Abbas Kiarostami, also made a very good documentary about that, Infidels (2003). We thought, wow, they are a great minority that no one has talked about.

After Titi and Zalava, I know that many filmmakers are going to make films about these gypsies. I know maybe one or two feature films in Iran. They are starting to make films about them. After watching these films, many filmmakers understood that gypsies are living in Iran, and why don’t we pay attention to them? Gypsies are living in cities now but they have a very strange connection with magic and fantasy, which absorbed us.

7R: Did you both meet with gypsies or cast them in the film?

Ida Panahandeh: I have met some of them. You can find gypsies in Tehran in every corner of the streets. They always are [buskers]. They play music, and unfortunately, they always beg for money. They are very very good instrumentalists. In Kurdistan, we have gypsies, but I have not ever met gypsies in Kurdistan.

Arsalan Amiri: Nowadays, they are not a very big population. For example, one of the musicians in the film was a gypsy. He is something like Kurd, but his roots are gypsy.

Ida Panahandeh: I wanted to use gypsies in my film Titi, but because Titi was a very difficult film to make, someone told me don’t use gypsies because you can’t control them, and they won’t obey you. You cannot tell them, “Okay, come to my set on Tuesday at nine o’clock, and you have to work until seven.” They don’t do that. They never do that; they are free. They come whenever they want. And they leave whenever they want. And maybe they will disappear for two weeks. So I decided not to use them.

But before making Titi, we met them. And I sent my assistant to one of the cities in the north to talk to them, to go to their cafes and do research.

7R: Can you tell me about the sound design in Zalava?

Arsalan Amiri: One of the complicated things in Zalava for me was the sound design and music. I couldn’t find a film in Iranian cinema or Middle East like Zalava that can inspire me for what I should do.

I wanted [the film] to remain in between genre movie and arthouse movie, and the sound should be like this. The mix of these two different ideas about sound was complicated because some sounds [my sound designer created] were very exaggerated to be like a genre movie [but it was too much because I wanted the film to still be] about reality. I didn’t want to use industry sound [like from Hollywood movies] to be scary. I wanted to use realistic sounds, like wind and cats.

Ramin Kousha did the music. He is a very talented Iranian musician. We felt that it should not be too much like classic horror movie [music], but something between atmospheric and narrative music.

Ida Panahandeh: Ramin was working on a Game of Thrones project. He is a very, very good composer. He lives in the US, but he’s Iranian. We talked with many Iranian composers. But the problem was that they were not particularly international [i.e., western music]. Arsalan wanted international music for this film.

Arsalan Amiri: We have traditional music in Iran, but if we use the traditional Iranian music, maybe some [international audiences wouldn’t] like it. I wanted to make a kind of international Iranian music, international Kurdish music.

Ida Panahandeh: Oriental, Eastern influences. While watching Zalava, in some parts, you can feel the taste of Eastern music that Ramin has used. Arsalan didn’t want to use Iranian traditional music. I like it. I like it too much. But Iranian music is so different from western music. Maybe [Western audiences] cannot understand it or feel connected to it. Mixing Iranian music with a genre film would be very challenging and risky so he decided not to do that.

Arsalan Amiri: I didn’t want to use completely pure western music because we made the film with Middle Eastern culture, Kurdish culture.

7R: When you’re thinking about the sound, how did you think about what you wanted to emphasize and what would be going too far?

Arsalan Amiri: Zalava gave my sound designer an opportunity to use everything he knows about sound in horror movies and drama movies. A difficulty I had was he wanted to put everything into the film to make a very powerful sound design.

Ida Panahandeh: In the first session, we went together to his studio to listen to the film, and we both were shocked. The sound designer is a very famous sound designer in Iran. He’s very famous and a very, very nice man. But he is fifty-something. In Iran, when you talk to someone who is older than you, [you are] very, very respectful, and very careful. We had to criticize him very, very smoothly. We were looking at each other, and we didn’t know how to start to talk to him.

Arsalan Amiri: You have to say what you want in another way. You can’t say, “Remove the sound.” You should say, “The sound is very good. It’s fantastic. But it’s better if you reduce it a bit [more],” [and] suddenly, you know, remove it.

When the sound designer first watched the film, he thought this is a genre movie. But we talked together, and he is very professional, very clever. And after discussing this, after two or three sessions, he understood my point. And then, we controlled the sounds. We removed many layers of sound [that he had added in which] was like [what you would have in a] Hollywood [genre] movie. We put some silence in. We wanted the atmosphere to be sometimes like a genre movie, sometimes like a melodrama. Some sounds should be smooth and warm, and some should be hard and very cold.

It was very difficult [to find this balance], but I’m satisfied with the results, and my sound designer is, too. He likes the film, and he thinks this kind of [hybrid] sound designing is new. It was a new experience for him.

7R: Ida, you’re listed as a director advisor on the film. What does that mean?

Ida Panahandeh: It means lots of discussions and fighting. We discussed a lot. We fought a lot.

I preferred not to go on set, because when I was on set, I wanted to do something as a director. It’s impossible for a director to be on set and keep silent. So I preferred to be away from Arsalan and his team.

I was in the editing room with the editor and watching all the rushes that came in. Every night, we had discussions with Arsalan. Every night, we talked about what I thought was great and what I thought he had to be careful about.

It was a very, very difficult project, let me be honest, because it was during the pandemic. No one was vaccinated. Still, we are not vaccinated in Iran. Arsalan was under pressure. Everyone had a mask, and every day, we were waiting for someone to have COVID, and we’d have to ask him or her to leave the project. The actors were a big concern, because if one of them had this COVID, the shooting would have to stop. We didn’t have money to stop the shooting and start again. It was a very difficult way for a first feature filmmaker. If I want to be honest, I didn’t expect Arsalan to make such a wonderful film. It was beyond my expectations.

7R: Arsalan, you have edited all of Ida’s films. What was it like to work with an editor to edit your own film?

Arsalan Amiri: For me, it was very easy. I thought, if the editor’s work is not good enough, I can edit it. I was relaxed. The editor was one of our old friends, Emad Khodabaksh, who we have known for twenty years. I told the editor that the film is in the hands of a trusted person. If Emad can not do it, Ida can do it, or I can do it. Because of that, I was very relaxed. And Emad did his job very well.

Ida Panahandeh: The editing process started simultaneously with shooting. In the hotel that we were staying in, we had a special room for the editor and his computers. Every night, when Arsalan came back from shooting, he could watch the shots of the day before.

It’s a kind of method that helps the director to make himself better, and to avoid mistakes. Or if they make mistakes, they can correct themselves after that. On Titi, we did that again, and Arsalan was in the editing room. This time, we switched our positions. We always do editing simultaneously with shooting. We have to do that.

You watch your shots, and you think that, okay, this shot is not something I liked. Or in one shot, the actor is not good, so you can repeat it. If you can repeat it, you have to do that.

Arsalan Amiri: In this film, we changed some scenes or I wrote another scene on set. I think 50% or 20% of the film was changed on set. Some parts I changed because of a tight budget. For example, if we couldn’t find a location we could afford, I changed three scenes, and wrote one scene [that we could use] instead [of these three scenes].

7R: What are you both working on next?

Arsalan Amiri: I’m thinking about making a Kurdish sci-fi movie with some black comedy. If I find the idea and story, I’ll try to do it. If not, I’ll help Ida make movies.

Ida Panahandeh: I’m working on a project which is a TV series. It’s based upon a true story about a couple in the ‘40s in Tehran. The man was the first artistic theatre director in Iran. His partner was an Armenian woman and a star in Iranian theatre. The man was in the Communist Party after World War II. He made a revolution in Iranian theatre. But unfortunately, because he was a very, very important part of the Communist Party, after ten years, they imprisoned him. He escaped from prison and went to the Soviet Union. When he left Iran, that was the end of the Iranian artistic theatre for decades. I hope I can make it.

You could be missing out on opportunities to watch great films like 200 meters at virtual cinemas, VOD, and festivals.

Subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter to stay in the know.

Subscribers to our newsletter get an email every Friday which details great new streaming options in Canada, the US, and the UK.

Click here to subscribe to the Seventh Row newsletter.