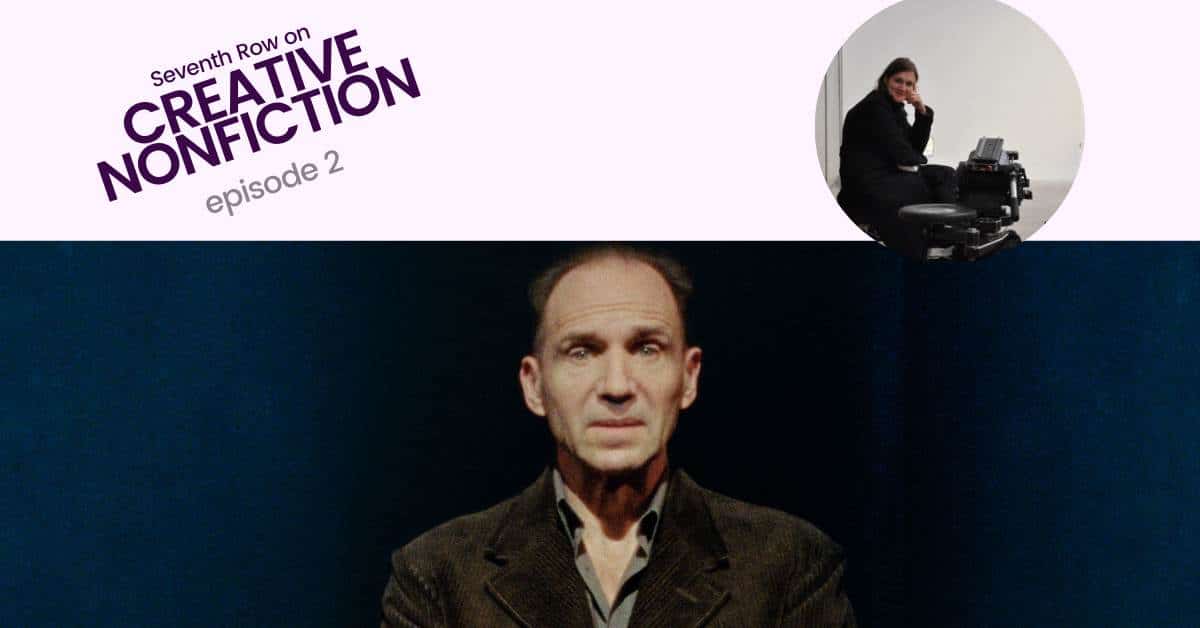

In the second episode of our Creative Nonfiction Film podcast season, Sophie Fiennes discusses Four Quartets and how she approaches documenting live performance on screen.

Don’t miss a single episode.

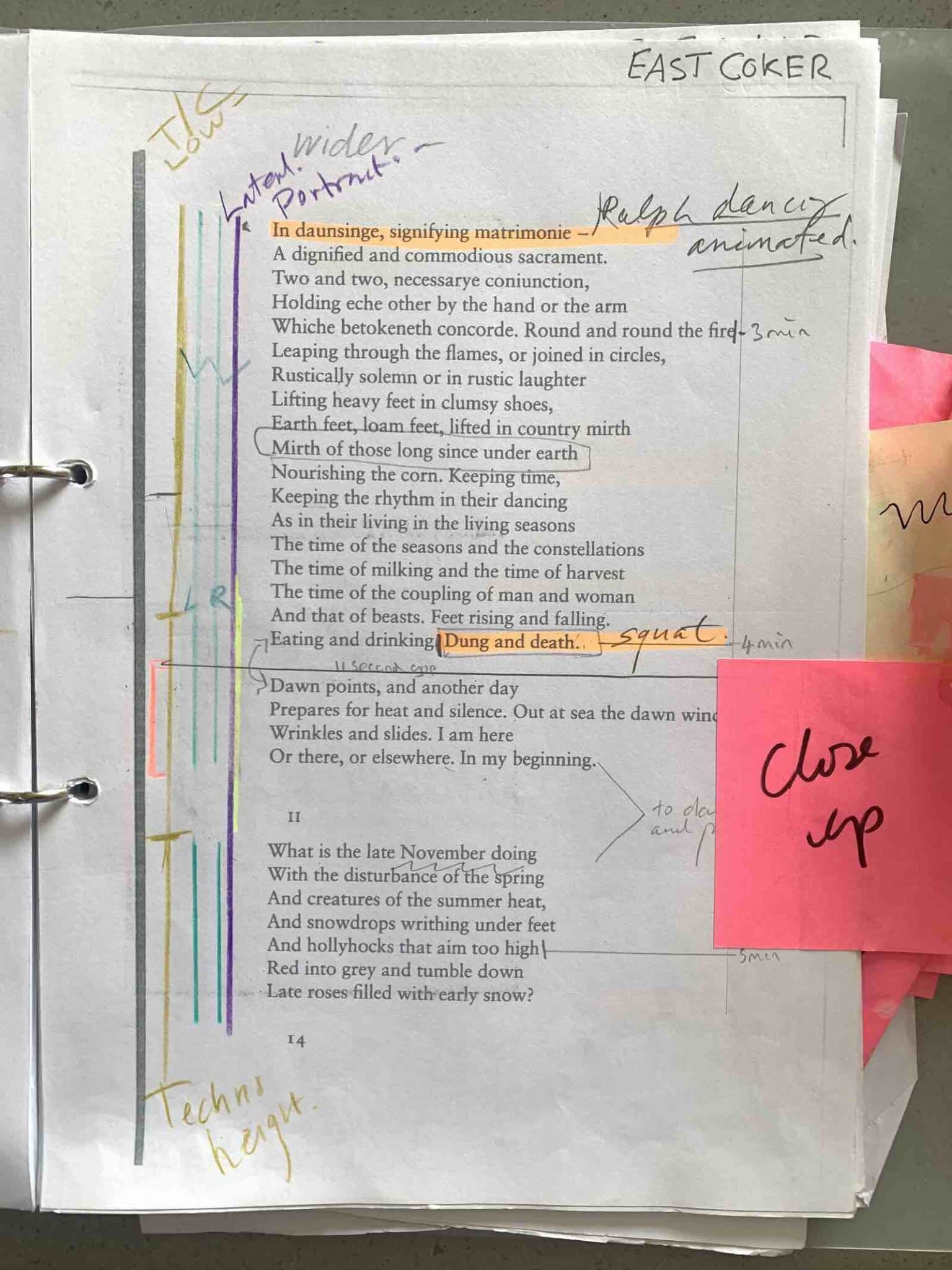

On episode 2 of the Creative Nonfiction Podcast Season, Sophie Fiennes discusses her new documentary, Four Quartets, in which she captures the stage play directed by and starring her brother, actor Ralph Fiennes. For the production, Ralph Fiennes adapted the T.S. Eliot poem for the stage — which was never originally intended to be performed that way — and then toured this production around the UK in 2021.

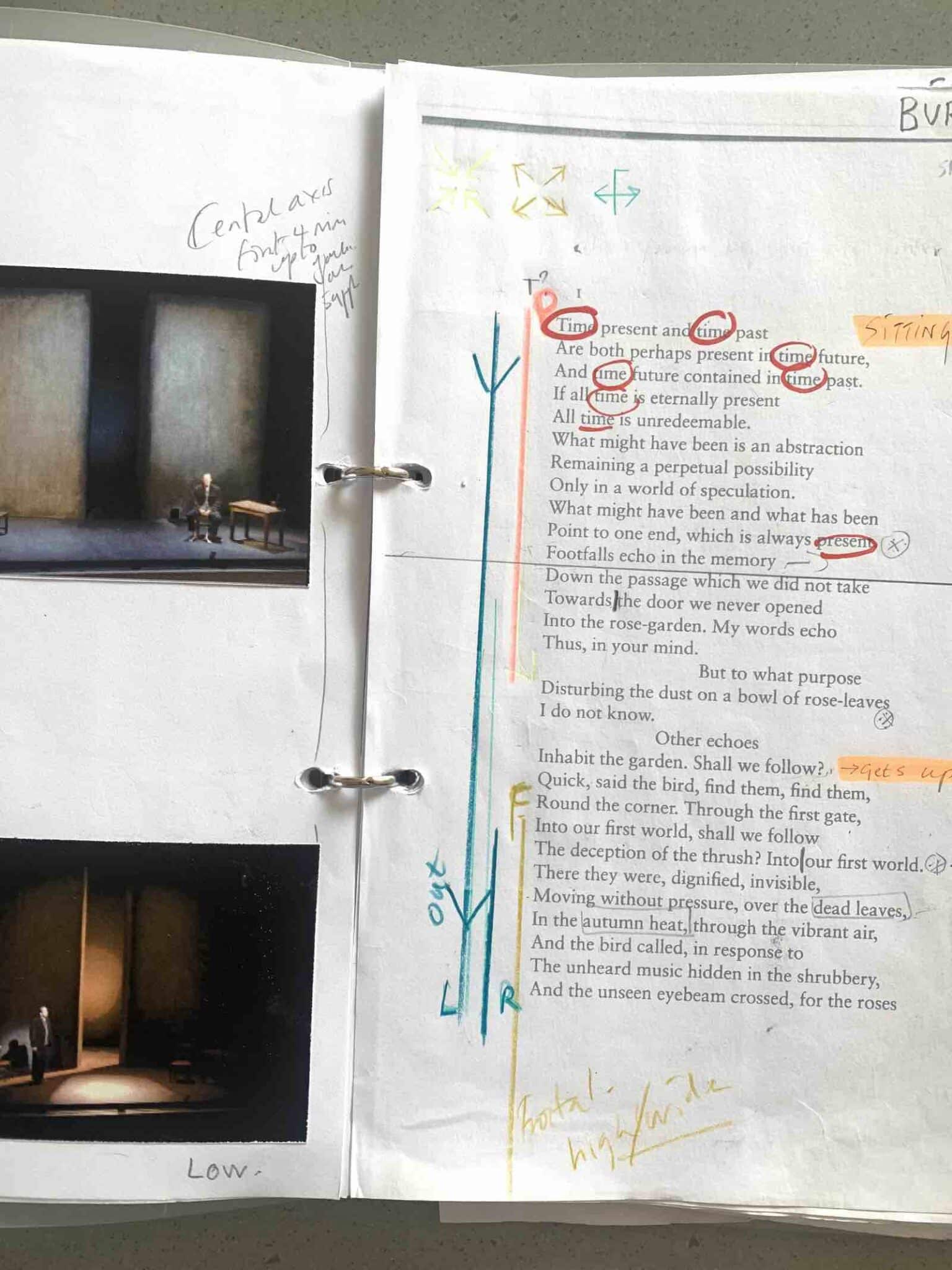

Sophie Fiennes’s film of Four Quartets is neither live capture nor a full adaptation of the play. Instead, Fiennes remarkably documents the theatre production on screen, maintaining all the original lighting and blocking. Her choices of framing and camera movement really puts us in the black box theatre with Ralph Fiennes. Unlike most recorded theatre, where there is a constant sense of information loss, Sophie Fiennes gives us a sense of the theatrical space so we get a better sense of what we’re missing when we’re missing it. It’s built into Sophie Fiennes’s direction.

Sophie Fiennes discusses Ralph Fiennes’s production, the challenges of documenting the play on screen, and how working with Declan Donnellan of Cheek by Jowl just before she shot Four Quartets changed how she thinks about acting and theatre.

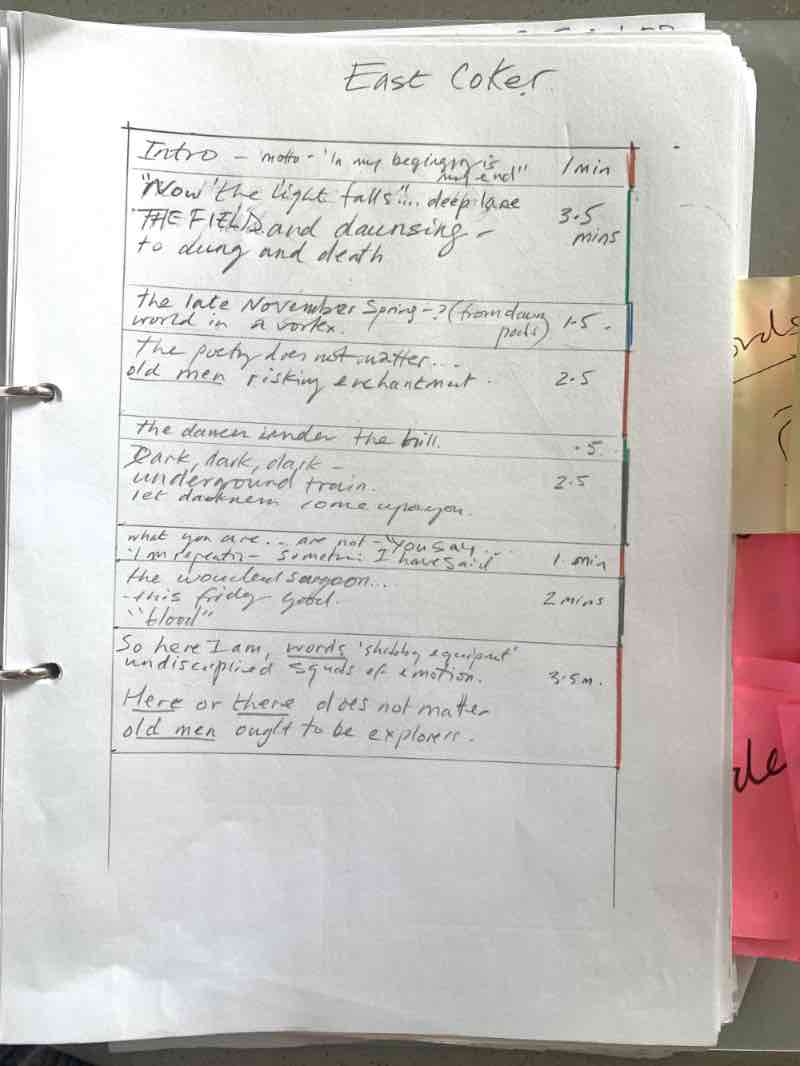

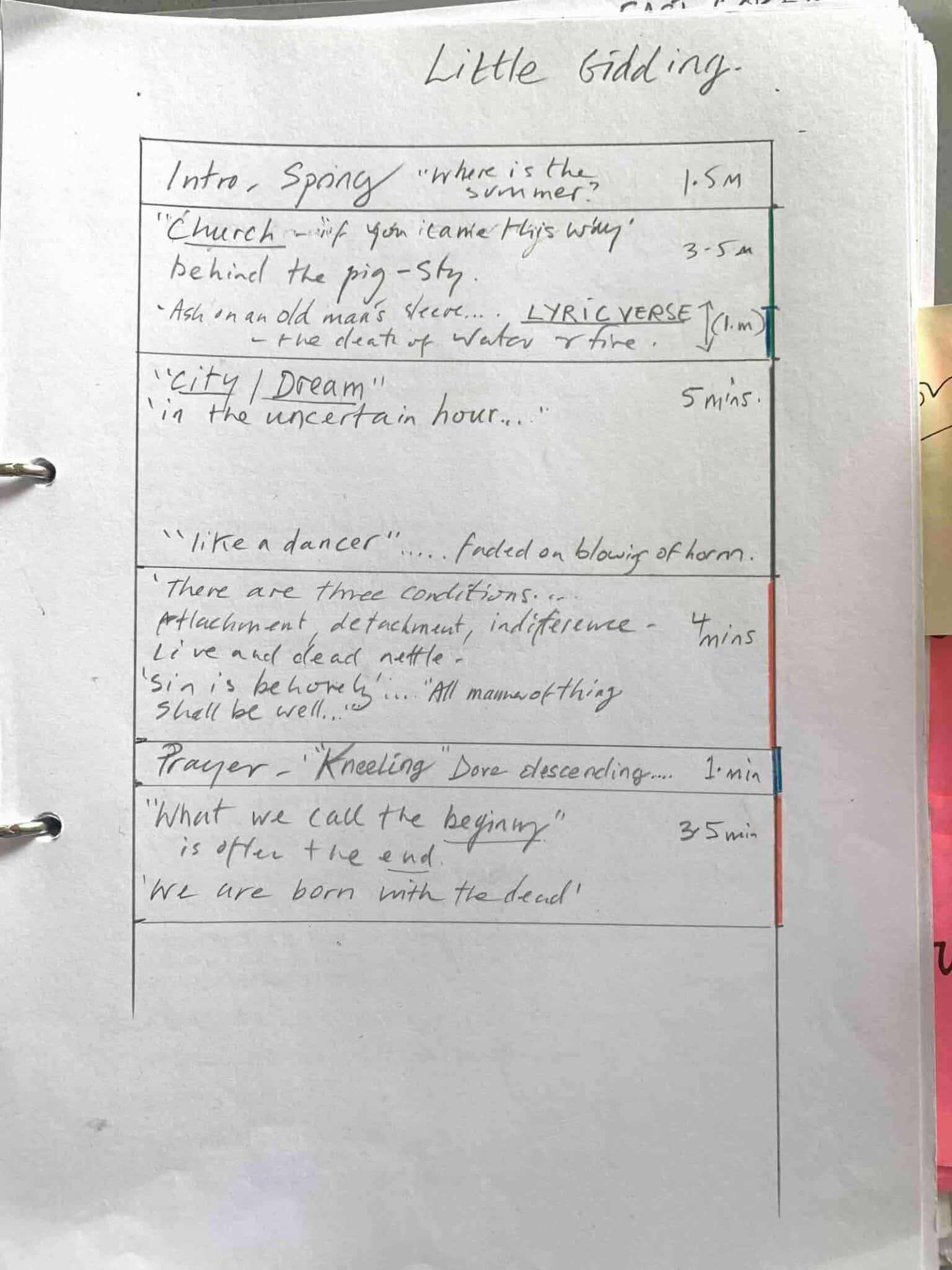

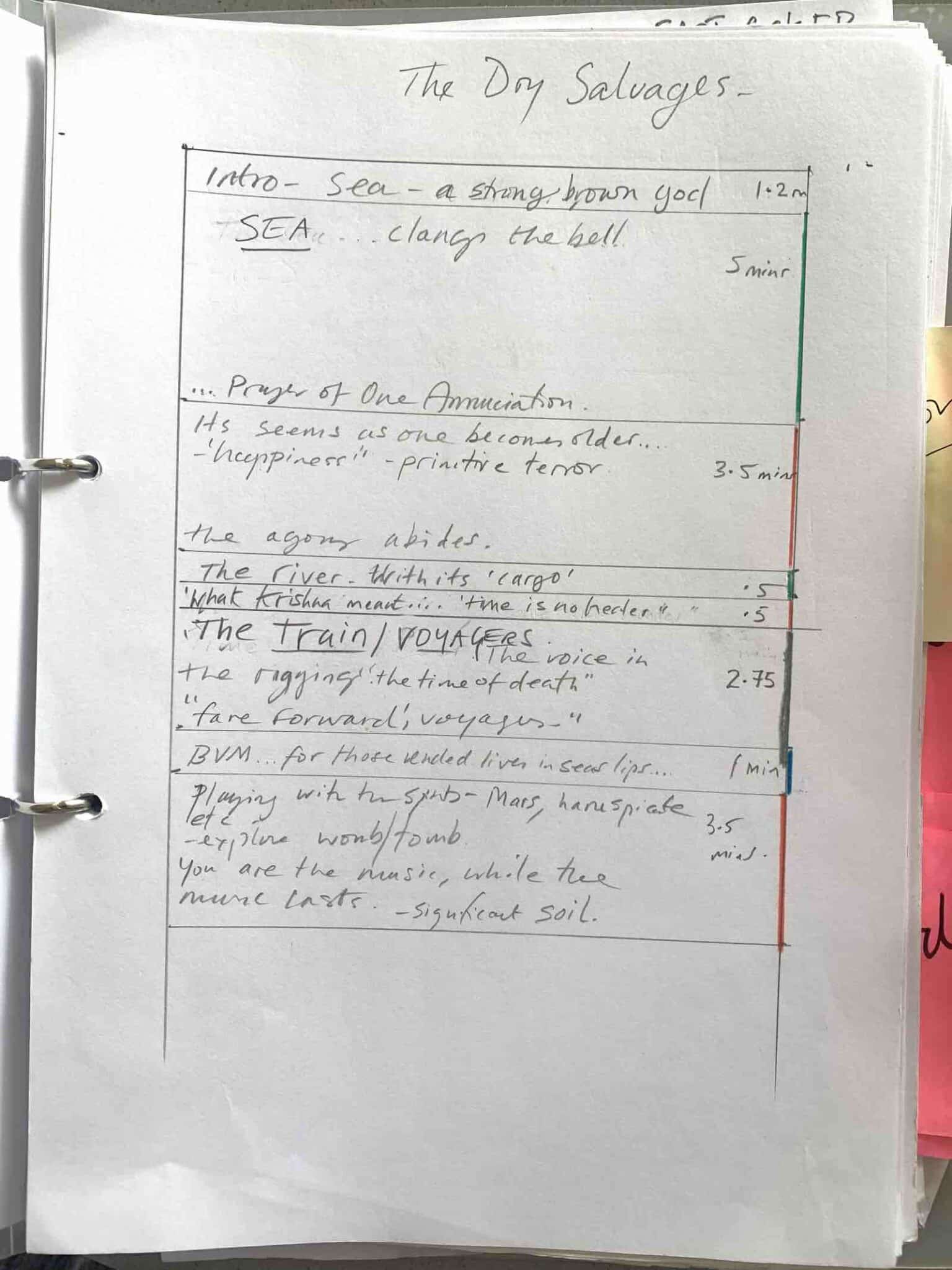

Excerpts from Sophie Fiennes’ director’s script for Four Quartets, which she refers to in the podcast interview

Show Notes for Creative Nonfiction Podcast Season Ep. 2

- Read T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets

- Listen to Cheek by Jowl’s Not True But Useful podcast episode on thresholds and space

- Read our interview with Sophie Fiennes on Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami

- Watch our masterclass on Creative Nonfiction with Carol Nguyen and Penny Lane

- Get your copy of the ebook Subjective Realities

- Get your copy of the ebook In their own words: Documentary Masters vol. 1

- Discover more Seventh Row writing on creative nonfiction film

- Become a member to listen to our entire archive of podcasts, including our past episodes in which we discuss creative nonfiction films.

Listen to the whole Creative Nonfiction season

In this 5-episode podcast season, Alex Heeney interviews four creative nonfiction filmmakers about their latest films and how they are pushing the boundaries of what documentary and nonfiction film can be.

Listen to all the episodes to discover how filmmakers are pushing the bounds of documentary cinema in 2023.

Never miss an episode again. Become a member.

The Seventh Row Podcast spotlights under-the-radar, female-directed, and foreign films. All of our episodes are carefully curated. Indeed, we only discuss films we think are really worth your time and deserve in-depth critical analysis.

Our episodes that are more than six months old are only available to members. In addition, many of our new episodes are for members only.

For exclusive access to all of our episodes, including all of our in-between season episodes, become a member.

Related Episodes on documenting theatre

- Listen to Ep. 49 (Members Only): Lungs: In Camera and Conversations With Other Women: Split-screen storytelling

- Listen to Ep. 60 (Members Only): Old Vic In Camera: Three Kings and Faith Healer

- Listen to Bonus Ep. 17 (Members Only): Saoirse Ronan and James McArdle in The Tragedy of Macbeth at the Almeida Theatre

- Listen to Ep. 98 (Members Only): Angels in America: Comparing two adaptations (HBO Miniseries + NTLive)

- Listen to Ep. 108 (Members Only): The Deep Blue Sea(s) Redux: Terence Davies’ film adaptation and Carrie Cracknell’s NTLive production.

Listen to all the related episodes. Become a member.

All of our episodes that are more than six months old are only available to members. Additionally, we have many bonus episodes and in-between season episodes which are also only available to members.

For exclusive access to all of our episodes:

Credits

Host Alex Heeney is the Editor-in-Chief of Seventh Row. Find her on Twitter @bwestcineaste.

This episode was edited, produced, and recorded by Alex Heeney.

Episode transcript

The transcript for the free excerpt of this episode was AI-generated by Otter.ai.

[fusebox_transcript]