Alex Heeney reviews Chase Joynt and Julietta Singh’s The Nest, a Gothic documentary about a haunted house that reveals lesser-known parts of Winnipeg’s intersectional history.

InsideOut Reviews: Sandbag Dam, The Nature of Invisible Things

Alex Heeney reviews Rafaela Camelo’s The Nature of Invisible Things and Čejen Černić Čanak’s Sandbag Dam at Toronto’s InsideOut LGBTQ+ Film Festival: two sensitive films about young people that young people should see.

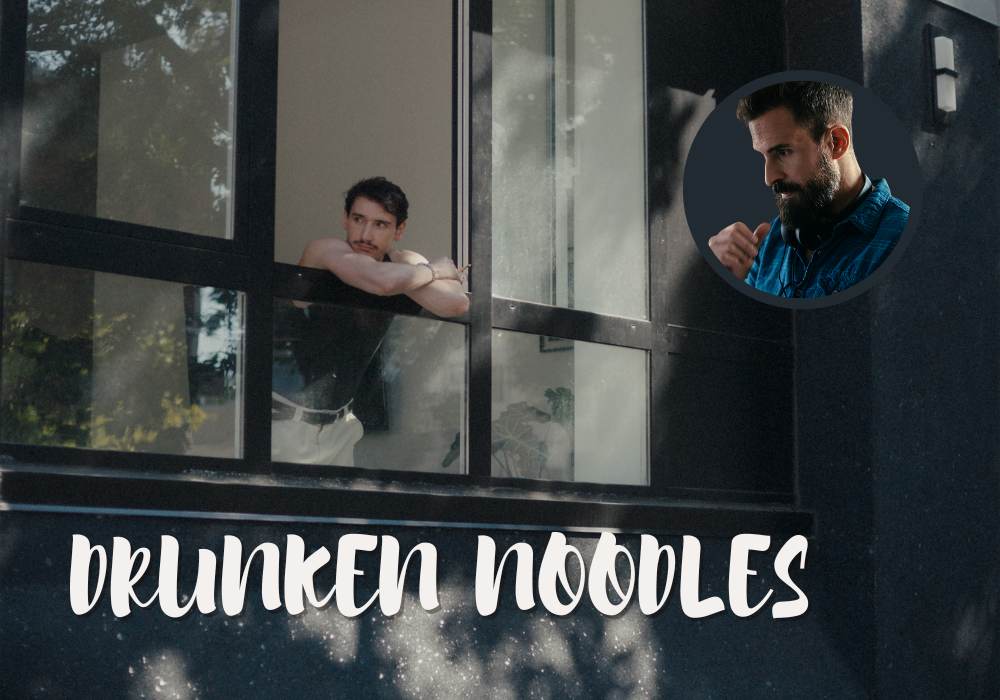

Interview: Lucio Castro on Drunken Noodles

In this interview, Lucio Castro discusses the total freedom of low-budget filmmaking for his queer Cannes ACID film Drunken Noodles.

Film Review: Pauline Loquès’s Nino at Cannes

Alex Heeney reviews Pauline Loquès’s feature debut, Nino, starring Théodore Pellerin, which screens in the Critics’ Week sidebar at Cannes. The film tells the story of a twentysomething man’s nervewrecking weekend after he’s diagnosed with c

ancer and before he starts treatment.

Film Review: Alice Douard’s Love Letters

Alex Heeney reviews Alice Douard’s debut feature Love Letters, which screens in the Critics’ Week sidebar at Cannes. The film tells the story of a queer woman in 2014 whose partner is pregnant with their child, and the paperwork involved with becoming her daughter’s legal parent.

Interview: Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne on The Unknown Girl

Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne discuss the making of The Unknown Girl, the sound design, and creating reality on screen.