Great editing is invisible, which means it often goes unnoticed. We pick the best editing of 2017, and explain why it is crucial to flow, tone, and rhythm. Read the rest of our best of the year content here.

The best editing is so good it’s invisible, which also means it often goes unnoticed. Muck up the edit, and a film’s rhythm and tone can get completely botched. Get it right, and the film just flows. It’s no coincidence that most Best Picture Oscar winners are also nominated for Best Editing — even if the academy regularly gets it wrong when it comes to the awards themselves. For our Best of 2017 series, we take a look at the five best examples of film editing from 2017.

Call Me by Your Name

In my piece “Tricks with time”, for our Call Me by Your Name Special Issue, I wrote about how director Luca Guadagnino and editor Walter Fasano use editing to stretch and contract time — putting us first in 17-year-old Elio’s (Timothée Chalamet) headspace, and then, more and more, in his 24-year-old paramour Oliver’s (Armie Hammer).

Although the film is centred on the love story between Elio and Oliver, we’re constantly learning about secondary characters. Many scenes involve multiple characters — at dinners, dances, and archeological excursions. These are not only the hardest kinds of scenes to direct but also to edit: how do you balance private moments for individual characters in closeup with the bigger picture of how characters relate to each other? Focus solely on the speaker, and you’ll miss crucial reactions, and vice versa.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘CMBYN editor Walter Fasano regularly prioritizes Marzia’s perspective by staying with her longer than a film only interested in Elio’s arc might.'” quote=”‘CMBYN editor Walter Fasano regularly prioritizes Marzia’s perspective by staying with her longer than a film only interested in Elio’s arc might.'”]

In every dinner scene or Perlman family gathering, we get a glimpse of how Elio’s parents relate to each other, their son, Oliver, and their friends. By the time Mr. Perlman gives his now legendary speech about first love lost to his son, his melancholy about his own missed opportunities and imperfect marriage doesn’t come out of nowhere: it’s been brewing, just beneath the surface throughout the film, as he watched the boys’ courtship with visible envy.

Similarly, although Elio’s girlfriend Marzia’s story never overpowers the main arc, Fasano provides moments that show how her relationship with Elio could have been just as meaningful for her as his relationship with Oliver is to him. Fasano regularly prioritizes Marzia’s perspective by staying with her longer than a film only interested in Elio’s arc might. Not only does the film open on Marzia, but Fasano lingers on her at key points: just before she looks out the window at Oliver arriving; while she waits to meet Elio to embark on a romantic relationship; and when, feeling insecure and uncertain, she confronts Elio about their relationship status. – Alex Heeney

Read our Special Issue on Call Me by Your Name here >>

Dina

Editor Sofía Subercaseaux only has six features under her belt, but her assured grip on the craft has already cemented her as a talent to watch. She has a knack for understanding a film’s tone and finding the exact right cutting rhythm to match, giving her work distinctive musicality. Christine is edited with the disjointed, staccato rhythm of its protagonist Christine Chubbuck’s (Rebecca Hall) anxious, isolated headspace. In contrast, Dina is more of an adagio, patiently observing daily life. Adapting to documentary filmmaking, Subercaseaux finds the right moments to linger in amongst mountains of footage depicting the most banal of everyday activities.

Dina is a serene and intimate film, about a recently engaged autistic woman named Dina Bruno. It plays out in a series of static, wide, long-take tableaus, allowing us to observe Dina uninterrupted — an attempt to present her life truthfully and to avoid exploitation. Subercaseaux’s work is minimal but elegant; she crafts the film’s slow, calming rhythm, allowing scenes to play out naturally, and always sensing the exact moment we should move on. – Orla Smith

Ex Libris: The New York Public Library

Frederick Wiseman’s films are made in the edit, which he does himself. After shooting hundreds of hours of observational footage, it takes him about a year to cull it down and organize it into the final film. He doesn’t stop until he can explain to himself why each scene is there, and why it appears in its current order: it has to build an argument. Even individual sequences are a feat of editing: paring down an hour-long meeting, into a 5-minute scene, in which each line appears to follow the next, even if they’re all taken from different points in the meeting.

Ex Libris is no exception: scenes of people typing on computers with headphones in the New York Public Library’s reading rooms punctuate the more vibrant scenes of community gathering, lectures, and performances. Wiseman envisions the library as a democratizing institution. The first hour of the film is about giving us an understanding of the role of the library today beyond a group of rooms to store books. The second zeroes in on how the modern library finds new ways of delivering information. And the third interrogates the way in which information is stored and catalogued: if our textbooks are written through a white supremacist lens, perhaps the very information we have access to is itself a problem. – AH

God’s Own Country

Editor Chris Wyatt and director Francis Lee assembled God’s Own Country so that the edits are as harsh, or as soft, as the film is. At the beginning, when Johnny (Josh O’Connor) is completely crushed by the sheer grind of day-to-day farm life, the cuts are hard, with a loud, handheld scene often following a quiet, calm scene. We feel the same jolt Johnny does. Similarly, the editing at the beginning mimics Johnny’s curt manner. After a casual sexual encounter with an auctioneer, who wants to follow it up with a drink and conversation, Johnny merely replies, “We? No,” and Wyatt immediately cuts to the next scene. Just as Johnny doesn’t give the auctioneer the time of day, neither does the edit. With the arrival of Romanian farmhand Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu) and his budding romantic relationship with Johnny, Wyatt’s editing strategy shifts. The cuts are less abrupt, less harsh: they soften as Johnny softens. – AH

Read our Special Issue on God’s Own Country here >>

Lady Bird

Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird is about not appreciating what you have until it’s gone. Similarly, the film is over before we know it, and before we’re able to process just how much weight its collection of seemingly insignificant scenes hold. Together, they form a comprehensive portrait of the turbulent, restless, and yearning period of adolescence.

Editor Nick Houy zips through Lady Bird’s life in only 94 minutes, hopping deftly from moment to moment. He replicates the restless energy of adolescence by cutting scenes short, and finds comedy in scene transitions — like cutting from Lady Bird petulantly throwing herself out of her mother’s car, to her wearing an arm cast at school. By not lingering on them, and cutting between actors in a simple, unflashy way, he doesn’t force significance — after all, Lady Bird doesn’t realise that these moments have shaped her until the end of the film, once they have already passed. – OS

The Levelling

Hope Dickson Leach’s feature debut The Levelling takes place in the waiting period between major events. The film’s drama derives from the death of protagonist Clover’s (Ellie Kendrick) brother, Harry (Joe Blakemore) — but it’s already happened when the story’s main action begins. The narrative builds to his funeral, but Leach ends the film just before it’s about to commence.

In place of ‘exciting’ plot, Leach focuses on how people, and their relationships, develop in the wake of grief. Editor Tom Hemmings and Leach starkly contrast the film’s prologue — a quick cut montage of disorienting images from Harry’s last night alive — with the present day. A title card marks the abrupt end of this visual noise, and we cut to a series of still, peaceful tableaus of the Somerset countryside. Each establishing shot is held for a leisurely length; this is the calm after the storm.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘Although THE LEVELLING is only 83 minutes long, editor Tom Hemmings takes his time.'” quote=”‘Although THE LEVELLING is only 83 minutes long, editor Tom Hemmings takes his time.'”]

Although the film is only 83 minutes long, Hemmings takes his time in the edit. We first see Clover sitting in a car with the man who has driven her to the farm where she grew up and where the film takes place. She’s about to be reunited with her estranged father, Aubrey (David Troughton). Hemmings allows the scene to play out in a single, unbroken take, held on Clover’s face, showing the self-absorption of her grief. We see her indignant anger at Aubrey, her reluctance to return home, and her sense of loss for her brother.

Hemmings’ patient and perceptive editing is especially crucial to depicting the relationships between characters. In a scene where Clover, Aubrey, and family friend James (Jack Holden) eat a meal together, Hemmings cuts between three over-the-shoulder singles. Clover feels isolated from the group; Aubrey in unsure how to deal with her discomfort; and James is the outside observer, watching this father-daughter dynamic play out, just like the audience. Aubrey succeeds in making Clover laugh, and after having withheld his singles, Hemmings cuts to his face; a sudden, surprising moment of warmth is foregrounded in their turbulent relationship. We stay on the scene for a while after the characters have stopped talking, observing the way their eyes flit silently to and from each other, processing the possibility that things might be able to change. – OS

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)

Jennifer Lame has been working small miracles on Noah Baumbach’s films for years: she edited Frances Ha, While We’re Young, Mistress America, and most recently, The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected). Baumbach’s trademark fast-paced, quick-talking films are inextricable from Lame’s careful editing, which give them their unique rhythms. Lame’s work on Meyerowitz may draw slightly more attention to itself because of the way scenes often end mid-sentence. But for a family incapable of listening to each other, or seeing beyond their own bullshit, it’s perfectly judged. As a series of short stories, these almost premature cuts draw attention to the way a family’s story is always unfinished. These “new and selected” stories give us merely a glimpse at how the family functions, not a comprehensive study. – AH

On the Road

Michael Winterbottom’s docu-fiction film, On the Road, which follows the indie band Wolf Alice on tour, with a pair of actors (James McArdle and Leah Harvey) woven into the group, is remarkably edited. Winterbottom captures the rhythm of the touring schedule, the daily grind of travel and performance, and yet also lingers on moments when the band connects and fools around. The few scenes in which the two actors are alone with each other, and develop a casual romance, are brief. We’re given just enough information to see how their characters have evolved on the road without lingering on these moments, each as fleeting as every city on the tour. – AH

Personal Shopper

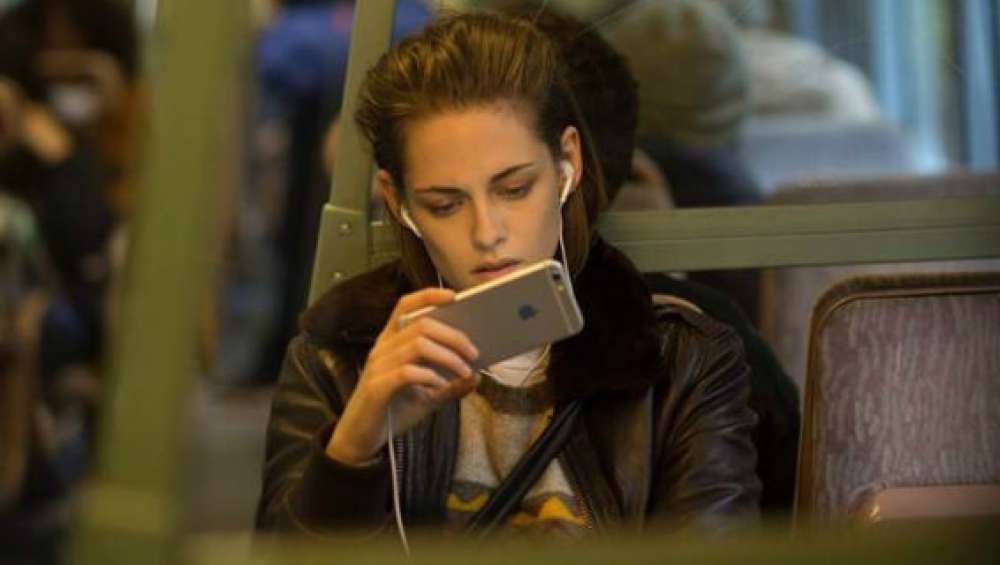

It takes an editing master like Marion Monnier to assemble a 20-minute set piece, involving a woman and her phone, and fill it with dread and tension. Yes, she had great footage from director Olivier Assayas, which found new and exciting ways to shoot text messages on an iPhone. But the edit is where the rhythm — of reading, replying, waiting, and getting inundated with messages after hours on airplane mode — is created.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘It takes a master like PERSONAL SHOPPER editor Marion Monnier to assemble a 20-minute set piece, involving a woman and her phone, and fill it with dread and tension.'” quote=”‘It takes a master like PERSONAL SHOPPER editor Marion Monnier to assemble a 20-minute set piece, involving a woman and her phone, and fill it with dread and tension.'”]

Monnier’s success with the central text messaging sequence alone would make her work on Personal Shopper noteworthy. She cuts scenes short, so that one day fades into the next: it constantly seems like Maureen (Kristen Stewart) is losing time, and we’re losing it with her. As Maureen is herself depressed, and often falling asleep as a scene ends, this sense of time loss also mimics her depressed state of mind. Maureen’s persistent exhaustion leaves room for ambiguity regarding the film’s supernatural elements: are these real or is Maureen dreaming or hallucinating? – AH

Read our Special Issue on Personal Shopper here >>

The Square

In The Square, co-editors Jacob Secher Schulsinger and Ruben Ostlund (who also directs) rely heavily on long, uncut takes, usually of reaction shots. It’s crucial to the film’s ethos: it is about how we react to art, so we spend the film watching the characters react to situations they find themselves in. Ostlund and Schulsinger often linger on reaction shots for what feels like an excruciating amount of time — even if, in reality, it’s just a few seconds — to allow us to viscerally feel the characters’ discomfort. It also gives us ample time to weigh their actions and judge them, which is crucial for the film’s satirical aspirations. – AH

Their Finest

Lone Scherfig is one of the few directors who excel at making ensemble films, ensuring every character gets their due. But it’s her work with editor Lucia Zucchetti on Their Finest, which ensures that Scherfig makes the most of her all-star ensemble cast — including Richard E. Grant, Eddie Marsan, Helen McRory, and Henry Goodman — in the final cut. Not only are we always able to track what’s going on with every character in scenes involving upwards of eight characters, but we get to spend time with each character at crucial moments. Eddie Marsan, as actor Ambrose Hilliard’s (Bill Nighy) agent, barely has any lines, but because Zucchetti lingers on his face as he’s unable to break the bad casting news to his client — and then on Nighy’s as he comes to this realisation — he feels like a rich, fully fleshed out character. Richard E. Grant’s studio manager speaks even less, but his reaction shots in a group meeting with his boss (Jeremy Irons) are priceless. – AH

Thelma

Joachim Trier’s films are so densely packed with ideas and information, without ever seeming like mental overload. Editor Olivier Bugge Coutté is instrumental to achieving this. As Trier’s first genre film, and his first feature that doesn’t rely heavily on essayistic montages, Coutté’s work draws less attention to itself here, but is no less important.

Coutté edits at a pace faster than the speed of thought that a complex film like Thelma requires. It’s not that it’s messy or relying on a short attention span — in fact, the long take of the university courtyard at the beginning of the film is among its most audacious scenes. Coutté always gives us just enough time on a scene or cut to allow us to start thinking about what it may mean, but he and the film move onto the next idea, the next clue, before the viewer has the time to finish thinking about the previous one.

For example, early on, we watch a snake slither into a hospital-like building, and then across the skin of an elderly woman. The camera’s focus is on the snake and its movement, but doesn’t linger on the woman. When Thelma discovers her grandmother has been hospitalized for years, we could connect that this woman we saw before is her grandmother — but we might not because the scenes are far enough apart that your brain may have thrown out the earlier information it didn’t understand.

Coutté and Trier do this repeatedly, with multiple plot lines, visual motifs, and ideas. Some get more time and are repeated more often, like the way the lights always flicker before Thelma has a seizure or invokes her powers. Some get little more than a few seconds: we see Thelma’s mother’s feet on the snow, and then stepping up onto the ledge of a bridge. The obvious conclusion is she’s about to attempt suicide, but we don’t have time to fully develop this idea because Coutté cuts before she jumps, or even really looks down. I forgot I’d even seen this scene until it was pointed out to me, and I watched for it again — I realised I’d seen it before but hadn’t fully made sense of it. This density of information, and the amount of ideas in the film, make it particularly rewarding on rewatch because there are always new intricacies to discover. Yet it’s all so seamlessly assembled that it never feels clunky or like it’s overreaching.

[clickToTweet tweet=”‘This density of information in THELMA makes it rewarding on rewatch, yet it’s all so seamlessly assembled that it never feels clunky or like it’s overreaching.'” quote=”‘This density of information in THELMA makes it rewarding on rewatch, yet it’s all so seamlessly assembled that it never feels clunky or like it’s overreaching.'”]

The film gets its uniquely eerie but intimate tone from the way Coutté mixes DP Jakob Ihre’s more formal camerawork with freewheeling, spontaneous handheld shots — often alternating between the two in the same scene. Slow, creeping shots of snakes, birds, and trees, especially in the first half, remind us that there’s something supernatural going on beneath the surface of this coming-of-age tale. At the same time, Coutté regularly edits to mimic Thelma’s thought processes: cutting to her phone as she checks it, following her journey online as she Googles or searches through Facebook, or bending the laws of time and playing with different angles to replicate the disorientation of hallucinating.

Because Thelma is a genre film, Coutté gets to experiment with the editing of key set pieces in order to ratchet up tension. The sequence at the Oslo Opera House is perhaps the most impressive: Coutté cuts between wide shots of the dance performance, wide shots of the audience, medium shots of Thelma and her paramour Anja watching, macro shots of their hand-holding and more, and shots of the chandelier starting to swing because of Thelma. In Coutté’s hands, the tension build in the dance performance, is intimately entwined with how the tension builds between Anja and Thelma and Thelma’s awareness of her powers being invoked. – AH

Read our Special Issue on Thelma here >>