B. P. Flanagan interviews Gwen director William McGregor about making a gothic horror film in the foggy atmosphere of Northwest Wales.

British director William McGregor’s debut feature, Gwen, trades on atmosphere. Set in vast Snowdonia in Northwest Wales, now a national park, McGregor’s film skillfully mines that escalating dread which defines some of the great British horror to create a film that dotes on their textural sensations. The pace of slow cinema, that feeling of watching time roll over us, is used to lull us into underestimating the shocking, bloody payoffs that come.

It’s a ghost story set against the coming onslaught of capitalism at the start of the industrial revolution. Eleanor Worthington-Cox holds the film together as Gwen, a teenager who is forced to take responsibility for her family after her mother (Maxine Peake) begins losing her grip on reality. The prospect of ghosts wreak further havoc on the farm where Gwen, her mother, and her younger sister, Mari, try to sustain themselves while they wait for the family patriarch to return from war. Peake lends the film a touch of prestige, going full throttle in a performance of anxiety and sickness that reveals different sides of the mother roles she often inhabits (in The Falling, Peterloo, and Private Peaceful). If she’s Toni Colette-like, often playing a mother, then this is her Hereditary.

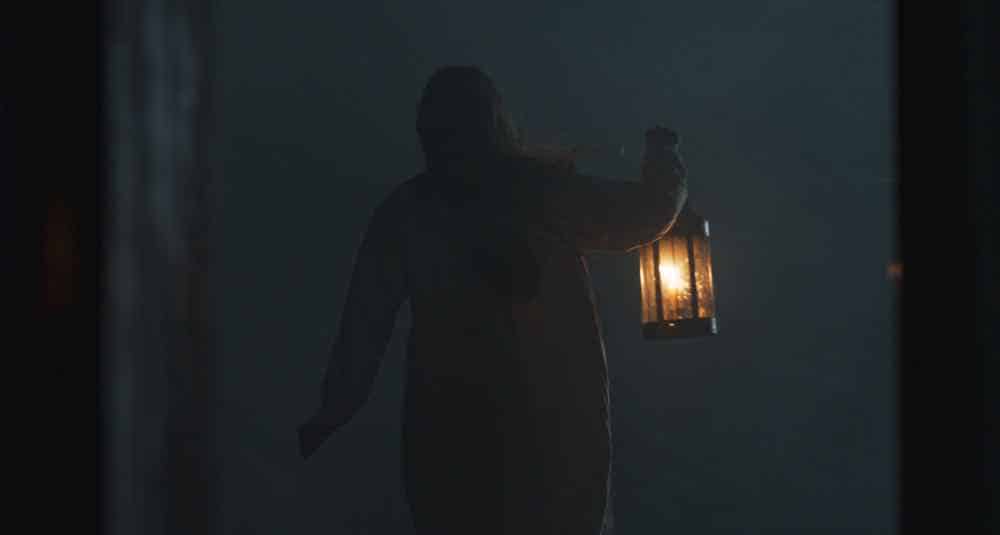

McGregor articulates his characters’ utter alienation by juxtaposing rich rolling hills with an imposing quarry and endless fog, creating a tension between the landscape and the havoc caused by agricultural and industrial waste. Then there’s the claustrophobia of the farmhouse itself, which is shot to emphasize walls and doorways, which separate Gwen from significant incidents, restricting her (and the audience’s) access to information. She becomes a limited observer. Gwen peers around corners to watch her mother’s confusing behaviour as her mother stares into a candle flame in the dead of night. Gwen’s youth and lack of worldly knowledge stop her from comprehending her situation. Much of the wider political context, like the church’s complicity in the destruction of the land, is depicted matter of factly and without exposition, leaving the viewer to infer the social dynamics that impact the film’s progression.

In a time when the British independent film industry is in a period of creative boom, with first-time filmmakers like Rungano Nyoni (I Am Not a Witch), Mark Jenkin (Bait) and Francis Lee (God’s Own Country) subverting festival audience expectations of the British indie, Gwen is a tense and expansive example of how, with the right support, an emerging filmmaker can defy the drawbacks of a low budget to fulfill an ambitious personal project.

Seventh Row (7R): As a man from Norfolk, an incredibly flat area in the East of England, why were you drawn to the craggy shapes of Snowdonia? How did you make it feel so lived in as an outsider?

William McGregor: I’ve always been inspired by landscape. I think that’s because I grew up on a farm, although Norfolk is a very different landscape to North Wales. Even my short films are inspired by the landscape I grew up in. I made a short called Who’s Afraid of the Water Sprite?, a fairy tale filmed in Slovenia. The producer [of Gwen, Hilary Bevan Jones], saw that at a student film festival in 2009. She has a lot of family from North Wales, and Gwen is the fourth time she filmed a production there. The way that I used the Eastern European landscapes suggested [to her] that I should go and look at North Wales [with a mind to] shoot a feature there.

I originally went with the intention of using North Wales almost as a set, like how I used Eastern Europe, to tell a fairy tale. But when I first went there in 2010/2011 to explore, it quickly moved away from a thoroughbred fairytale into being something inspired by the landscapes. The script came from exploring the area and doing historical research.

7R: Did you encounter a lot of fog there? The characters try to move through this fog in almost every scene…

William McGregor: Wandering around that landscape, you’re going to get lost in it, or see rain fronts coming in at you where you see that first wall of rain coming off a mountainside. It’s such a part of the landscape and atmosphere. It’s just there; it’s the world you’re shooting in; and it’s a pain when you’re trying to shoot a feature film. But it has such atmospheric value on screen. Just trying to survive in that wilderness, the isolation becomes a part of the drama in itself.

7R: There’s a massive negotiation going on between the landscapes and these interior scenes, where your genre instincts really kick in. How do you navigate these different spaces?

William McGregor: It’s important to me that the interiors weren’t studio built, that they are these spaces. They’re tiny, and they are cold, and I think that probably informs how we decided to cast them.

I wanted it to feel grounded. Although there’s the supernatural in the film, I wanted it to feel naturalistic — not in a handheld way, but for the light to feel natural. Candlelight. Light through windows. That’s so helpful for tension and genre, because it’s naturally quite dark, with just pools of light. You’re always looking out for what’s hiding in the shadows.

7R: Doors and windows are so prevalent. You use offscreen space very cleverly, hiding information from us. It draws us away from an outside perspective and into Gwen’s perspective.

William McGregor: It’s a part of trying to build dread. I wanted a film that’s an atmospheric experience as much as you go on a journey with this character and see the world through Gwen’s eyes. Her journey is going through the atmosphere and making sense of the world around her.

A part of building that dread is just a window of a doorway creating a narrower field of view, things out of sight lurking around the doorway. All those little bits add towards a feeling of unease.

7R: How do you balance your visual style with the sound design?

William McGregor: It comes from what creeps me out. Growing up, I’d hear foxes outside at night and not know what it was. Or even when I did know, the sound of my cat fighting… it’s just uneasy at night when you hear rodents in the loft scratching around. Everything puts you on edge, and I wanted to convey that.

I really reduced the music, nothing to push you this way or that. Just keep it eerie and use the wind to create a soundscape. And then I did little things like the nursery rhyme, the lullaby [sung by Gwen to comfort Mari when she misses their father] — burying it in the wind in the beginning, so there’s these little undertones rather than a big piece of music that would have drowned it out. I think it would have lost the tension.

7R: You keep talking about your childhood, but the film is so much about modern anxieties.

William McGregor: It just seeps in. We’re always worried. This story could be considered folk horror, [in keeping with] the current reemergence of that particular sub-genre, which has coincided with a concern for a loss of connection to the landscape that we come from.

The more streets and concrete we’re surrounded by, the more people feel an urgency to get back to the grassroots of things, which is probably why I was drawn to this kind of story. I think there’s others like it around, as well. Your anxieties find their way in there somehow.

7R: How do you navigate the use of genre technique and your genre influence? Sometimes, it feels like a British art film, and at other times, it’s incredibly Gothic.

William McGregor: I love horror and folk horror, and I love gothic ghost stories. M.R. James, The Unholy Trilogy [Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) The Wicker Man (1973), three films considered the progenitors of folk horror]… It’s just what I love watching. Even some BBC Plays for Today like Robin Redbreast (1970).

What I like is really creepy landscape-driven horror. I have to be careful with how I label this film because if I say it’s a horror film, and someone comes in with a certain expectation, they’ll say, “I’ve just watched 20 minutes of a weird, eerie arthouse film, and I want my money back.”

At the same time, I was given an opportunity at the BFI, as a first time filmmaker, where they just wanted to see what I could do. I didn’t have the expectations of a commercial production, where I would have been made to put in more music or a jump scare at the beginning, and not been able to embrace the slow burn. It’s that freedom of it not being overly trapped in a commercial engine by the financiers which means I can be a little bit more experimental. It basically meant I made the film I like and enjoy, which is creepy and uneasy and grows into horror.

It feels right for this movie that this young girl is trying to make sense of the world and the unsolved mysteries around that. Naturally, it gets darker and darker. It made sense for this story, although it does make it difficult to position. The market has taken a different approach in defining what the film is, which means I’ve made a slight oddity. But I do consider it horror. With caveats.

7R: A lot of the social horrors come from the church, which acts as a gateway between the past and future and drives so much of the movie. How did you go about approaching religion in the film?

William McGregor: Another reference is The Devils (1971), which has a scene in it that’s never been screened because it’s too inflammatory and was banned. But that film hugely inspired me: it’s questioning belief and questioning reality as it’s presented to us. That’s another reason why I look at religion in the film and look at folk belief and questioning the reality of stories we are told. Are they for your benefit or someone else’s? I just look at it as another belief system, another narrative — without wanting to offend anyone [laughs].

7R: The church has such a place in the Gothic tradition, especially when it comes to women having information withheld from them.

William McGregor: And with accusations of witchcraft in general, which started as women with knowledge and power that men were afraid of, and the men trying to take that away from them. Be they herbalists or midwives or whatever, that suspicion through lack of information is very prevalent — especially now that we are bombarded with and manipulated by information, which is used to turn people against each other.

7R: Did you find yourself filming, or even editing, a star like Maxine Peake differently than some of the lesser known or more local actors?

William McGregor: Not really. I wrote her a long letter originally to get her on board. We have similar tastes, and I think the film is saying things politically that she wants to talk about so that encouraged her to come on board.

Whether it’s Eleanor [Worthington-Cox] or Jodie [Innes, who plays Mari] or Maxine, if they have ideas, you want to take that on board, especially as a male director. But ultimately, Maxine just wants to do the work to tell your story.

7R: So it was a very collaborative set?

William McGregor: The DoP, [Director of Photography Adam Etherington], and I worked together as students. We go back a long way. It’s nice [to make] films and have your friends around you. Even though it’s a difficult shoot, it’s a fun process!

Discover how Maxine Peake approached Peterloo in our ebook

We interviewed the Gwen star in our ebook Peterloo in process: A Mike Leigh collaboration. Read the book and become an expert on Leigh’s unique process.