As part of our celebration of Canadian Cinema leading up to The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook‘s release, we asked Canadian critics and filmmakers to pick their favourite Canadian film of the decade and tell us why. This list is a great overview of some of the best Canadian films of the decade.

It’s not a coincidence that so many of these picks feature 2019 films, a landmark year for Canadian cinema. Catch up with some of these films and more by taking the Canadian Cinema Challenge and prepare to dive deep into the best films of 2019 (and the decade!) by pre-ordering your copy of our forthcoming ebook, The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook.

Eligibility: Any film that had its world premiere between 2010 and 2019 and was made by Canadian citizens and/or permanent residents (but not necessarily set in Canada).

Sonya Ballantyne (@Honey_Child), Filmmaker

My favourite Canadian film of the last ten years is Goon. It was a tough choice as there were a lot of good choices such as Grave Encounters (The Vicious Brothers, 2011), Rebelle (Kim Nguyen, 2012), Angry Inuk (Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, 2016), and Birth of a Family (Tasha Hubbard, 2017). But I chose Goon because it is crass, it is bloody, and it is so funny! For the longest time, Canadian films, to me, have always been a synonym for “boring.” Goon lets us get crass and vulgar. Plus, the fact that it was filmed in Winnipeg and has a scene of my sister screaming in the arena stands during the main team’s game against a Quebec team also helps.

Bill Chambers (@FlmFrkCentral), Editor, Film Freak Central

My two favourite Canadian films of the decade are Carlo Guillermo Proto’s Resurrecting Hassan and Jason Buxton’s Blackbird; the former is a documentary, and the latter feels achingly plausible. Resurrecting Hassan follows the Hartings, a Montreal-based family of subway buskers: father Dennis, mother Peggy, and daughter Lauviah. All three are blind. There was a second child, Hassan, who drowned at the age of six (he was not blind). Proto matter-of-factly documents their home and work lives and the journeys in-between, how they coordinate when it comes to accomplishing mundane tasks, essentially becoming one. But the loss of Hassan has clearly left fissures in their relationship, with Peggy cheating on Dennis emotionally, if not physically (yet), and Lauviah seeming isolated in scenes with her cat. Dennis and Peggy are looking for a Monkey’s Paw to put it all back together and believe they’ve found it in the teachings of Grigory Grabovoy, a Russian faith healer whose outlandish theories have the Hartings convinced that Hassan can be brought back from the dead. The variables here are unique, to say the least, but the emotions are universal. Resurrecting Hassan is an inspired and devastating film about a pet subject of Canadian cinema: grief, which proves an insurmountable burden even for the Hartings, who live lives of constant adaptation. Not a week goes by that I don’t wonder how they’re doing.

Unsentimental yet deeply affecting, Blackbird is about a shy, harmless goth kid named Sean (Connor Jessup) who laments the sports culture around which both his high school and hometown revolve. (Even his dad drives the Zamboni at the local rink.) Sean vents his spleen in a Columbine fantasy that he posts to the web, in the heat of the moment, and soon finds himself in a youth detention centre alongside actual violent offenders. Told with a rare mix of humanity and procedural clarity that recalls the late, great British filmmaker Alan Clarke (who attended film school in Canada), Blackbird feels quintessentially Canadian in joining — and towering above — the ranks of school shooting movies without firing a single bullet on screen, as well as in its subtle critique of our tendency to over-prize athletes and athletic prowess, to the point where even a small-town courtroom begins to seem like an arena where those with power must impress. When Sean is handed a restraining order with 47 names on it, that’s 47 people who could rob him of his freedom on a whim; who’s supposed to be afraid of whom, again?

Anne Émond (@LaAnneEmond), Filmmaker

I chose Les démohttps://seventh-row.com/2016/03/29/philippe-lesage-demons/ns, the first fiction film by Philippe Lesage. To me, it is one of the most brilliant films about childhood ever made. It’s frightening, it’s funny, it’s deep, it’s dangerous, it’s heartbreaking. It’s life, condensed.

Alex Heeney (@BWestCineaste), Editor-in-Chief, Seventh Row

Sarah Polley’s film is more creative nonfiction than documentary: a film about uncovering and unpacking her family’s history that is itself designed to draw our attention to the art of storytelling on film. Reenactments that feel like home videos can be mistaken for fact, and interviews with multiple people in the family reveal often conflicting perspectives. Polley lets us see herself in the frame with a camera or in direct dialogue with her subjects, as a reminder that not only is she choosing the questions and directing the conversations, but also curating the footage and how it’s presented. Many people tell their stories in this film; Polley gets the final say in the cutting room.

As an adaptation from stage to screen, Mouthpiece is already a marvel: the way the action is set so specifically in recognizable Toronto haunts, the essential close ups revealing the characters’ vulnerability, and the flashbacks that feel so real you forget that the actresses who play grown up Cassandra (Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava) were rarely in the same room as their mother (Maeve Beatty). And yet this film is so much more: a feminist statement about what it means to be a modern woman, the sacrifices made for career and family, the conflicting feelings of being a heterosexual woman who does not want to be controlled by the patriarchy, the way women especially police and perform for themselves, and the crippling nature of grief. But I think its greatest power comes from the film’s main conceit: Cassandra is played by two actresses, a physical literalization of her conflicted self — in sync at times, and actively combative at others. I’ve talked about Mouthpiece twice on the Seventh Row podcast and interviewed director Patricia Rozema and her co-writers and stars Norah Sadava and Amy Nostbakken. And I’ll be thinking about and rewatching this film for years to come.

Honourable Mentions: Philippe Falardeau’s hilarious and brilliant political satire, possibly Canada’s first on film, My Internship in Canada, made me laugh more than almost any other film this decade while challenging me to think about both the nature of democracy and Canadian specifics. Rhymes for Young Ghouls is an entertaining, horrifying, and visceral look at the residential school system, a film with images that still haunt me years later, and helped me understand this atrocity in a way history lessons never did. And Anne Émond’s Our Loved Ones wowed me with its depiction not just of cycles of grief but the way touch keeps a family together and ties us to our physical existence.

Mouthpiece is featured in our forthcoming ebook on Canadian Cinema, The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook. Pre-order your copy now here.

Chris Knight (@ChrisKnightFilm), Chief Film Critic, National Post

I remember being amazed, engaged and ultimately moved (to tears!) by Sarah Polley’s intensely personal yet ultimately universal documentary Stories We Tell. Put simply, it’s the tale of Polley’s search for her biological father, after learning that the man who raised her was not. But there is so much more here — how family mythology is drafted and crafted over generations, how one truth begets others, and even how editing (whether of our memories or our films) helps shape the narratives of our existence. Trying to sum up this glorious experience, I wrote in my review at the time: “In the ocean of truth, we’re forever treading water, swimming for our lives.”

But choosing one “favourite” Canadian film is a difficult assignment. Canada produces great docs both large (Anthropocene, Jennifer Baichwal, Edward Burtynsky, & Nicholas de Pencier, 2018) and small (The Woman Who Loves Giraffes, Alison Reid, 2018), fabulous French-Canadian dramas like Tu Dors Nicole (Stéphane Lafleur, 2014) or Café de Flore (Jean-Marc Vallée, 2011), hard-hitting sci-fi like the recent Level 16 (Danishka Esterhazy, 2019), superb comedies (always an under-appreciated genre) like The F Word (Michael Dowse, 2013) and Project Avalanche (Matt Johnson, 2016), and powerful First Nations stories such as Edge of the Knife (Helen Haig-Brown & Gwaai Edenshaw, 2018), shot entirely in the Haida language. To say nothing of the work of Canadian directors on the world stage; my favourite films of three of the last four years have included work by Denis Villeneuve — Sicario (2015), Arrival (2016), and Blade Runner 2049 (2017). We are a nation blessed with filmmaking riches.

Interviews with the filmmakers behind Anthropocene and Edge of the Knife appear in our forthcoming ebook, The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook.

Joe Lipsett (@BStoleMyRemote), Film Journalist, QueerHorrorMovies.com

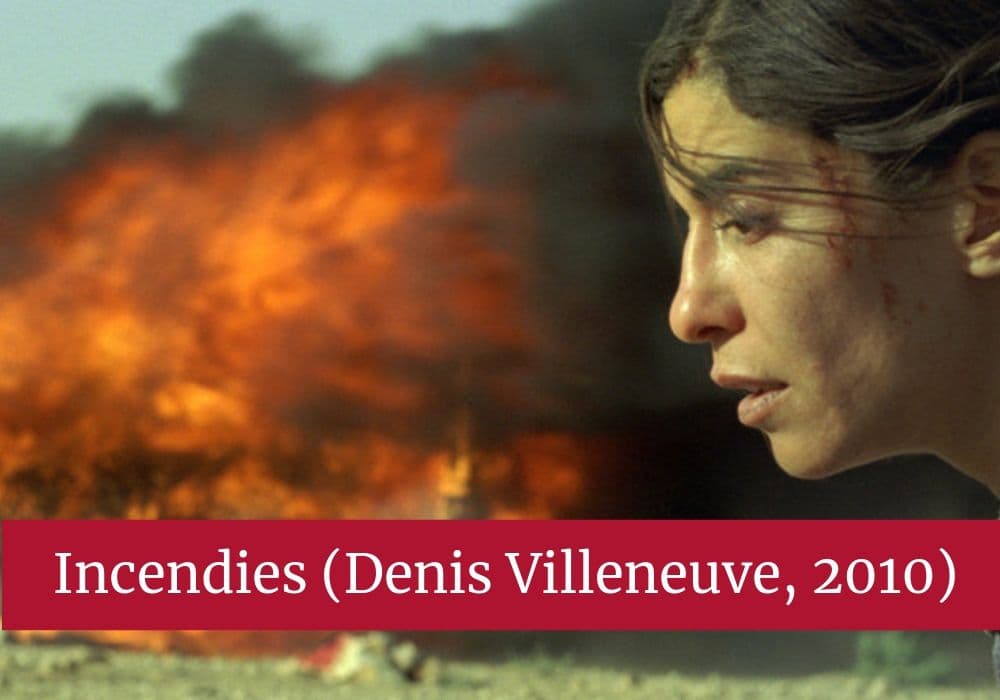

If there is one director who exemplifies new Canadian cinema, it is Denis Villeneuve. The Quebec screenwriter-director has broken big on the international scene in the last few years, but his films have always been emblematic of the tension between intimate, character-driven moments and large scale, bombastic action sequences.

Incendies is ultimately a benchmark film both in Villeneuve’s career and in Canadian cinema. It is the last “truly” Canadian film that the director made before he went Hollywood (yes, Enemy (2013) is small-scale, but it still stars US mega star Jake Gyllenhaal).

Incendies tells the story of twin siblings who travel to the middle east to uncover their own history; it is unabashedly a precursor to Villeneuve’s more mainstream fare in that it features scenes of torture, gripping tension and explosions. It remains at its heart, however, a film about searching for identity — a quintessentially Canadian notion that is baked into the film’s puzzle-box structure, as well as its status as a co-production with France and its multilingual approach to dialogue (English, French and Arabic). It is a blisteringly political film that is shocking, graphic and tender in equal measure. Incendies proves that Polytechnique (2009) was no fluke; the film would ultimately go on to be the first Canadian nomination in the Best Foreign Film category at the Oscars in nearly half a decade.

Pat Mullen (@CinemaBlogrpher), Online Co-Editor, POV Magazine

There isn’t a better example of the need to tell our own stories than Sarah Polley’s documentary, Stories We Tell. The deeply personal film, brought to life by Polley’s desire to take hold of the narrative when a family secret risked exposure, meditates on the right one person has to tell another’s story. As Polley digs deeper into her family history, the film interrogates the variations of the truth that arise when memories are fragmented and refracted over time.

Polley pushes the barriers of documentary by running with producer Anita Lee’s suggestion to extend one family’s story to the collective act of storytelling. This shape-shifting plays with perception and notions of truth and fiction — and the presumed authentic truth of documentary — to better understand the family Polley thought she knew as perspectives from invested parties and peripheral players piece together the story of Sarah’s mother, Diane, and her biological father.

Atop the layers of interviews and the jovial Margaret Atwood-infused narration by Polley’s father, Michael, Stories We Tell creates a kaleidoscopic memory game with archival footage and re-enactments seamlessly blended together. Polley’s puzzle challenges our desire for clean-cut narratives, as well as documentary’s presumed authority and factuality. More impressive than the film’s formal dexterity and its interplay between truth and fiction, however, is the pure and honest bond of familial love that unites the storytellers as Polley and her family explore a tale that could have easily divided them. Who says all happy families are alike?

Honourable mentions: Incendies, Mommy (Xavier Dolan, 2014), The Apology (Tiffany Hsiung, 2016), Les affamés (Robin Aubert, 2017), The Forbidden Room (Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson, 2015)

Brett Pardy (@AntiqueiPod), Associate Editor, Seventh Row

Métis writer Chelsea Vowell wrote “I strongly believe that every adult living in Canada should watch this film (though there are more trigger warnings for this film than I can count, so please take care)” because it was a “a glimpse into something none of us really want to see but must face.” In a time when political art is so didactic, Rhymes for Young Ghouls stands out for its brilliant use of genre film language, mixing horror, grindhouse revenge, and post-apocalyptic imagery to express the very real horror of Canada’s colonialism. What sets Rhymes apart from many “revenge fantasy” films is that it remains mindful of how violence affects characters and produces and reproduces trauma that flows through generations.

C. J. Prince (@CJ_Prin), Film Critic

It’s probably a basic pick, but I’d be lying if I didn’t pick The Forbidden Room as my favourite Canadian film of the decade. Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson’s remake of lost films bends, twists, and distorts itself to turn cinema into a living, breathing, pulsating organism existing through time. It’s hilarious, exhausting, and fully aware of everything unique about film that makes it so great. But I’d rather use the rest of this space to promote other Canadian titles, all of which are terrific and should be sought out: Invention (Mark Lewis, 2015), Our Loved Ones (Anne Émond, 2015), Tu Dors Nicole, and First Stripes (Jean-François Caissy, 2018).

An essay on First Stripes and an interview with the director appear in our forthcoming ebook, The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yeabook.

Sophy Romvari (@SophyRomvari), Filmmaker

Undeniably, it takes a certain level of courage and a definite amount of risk to make a film that is truly inward looking. When the correct balance of formal distance and emotional authenticity is struck, it evokes a special kind of empathy in the viewer. Personally, I find this type of work to often be the most rewarding cinematic experiences. Two examples that come to mind when I look back on the last ten years of Canadian cinema are Joële Walinga’s God Straightens Legs and Kalina Bertin’s Manic.

In both cases, these films are debut features, which is all the more astounding. Both films look at trauma within the framework of the filmmaker’s own family and tell stories that are captivating, compassionate, and unrelentingly honest. God Straightens Legs is a story about the filmmaker’s mother, who is resisting conventional cancer treatment due to her religious beliefs, but there’s never an ounce of judgement. The film is filled with love, mystery, and a wonderful element of fantasy. Manic, on the other hand, is an epic uncovering of family secrets, and a raw depiction of trans-generational mental illness, but is also extremely tender and patient. Mental illness is, of course, often sensationalized and can lead to further stigmatization, but Manic makes consent and collaboration part of the very fabric woven into its depiction of these difficult experiences, humanizing them in a way that is rarely achieved.

I feel humbled and empowered to have both of these women as role models to look up to within my own country.

Mary Angela Rowe (@LapsedVictorian), Editor-at-Large, Seventh Row

My Internship in Canada didn’t get enough credit. It was too Canadian for international viewers, who questioned its gentle brand of comedy, but Canadian audiences didn’t flock to it either. Everyone missed out, because this film is a rare bird: a political farce that delivers bite without scorn, a send-up of small town Canada that isn’t small-minded, and an odd-couple buddy comedy where nobody gets stuck being the straight man. It’s also hilariously funny, and unabashedly Canadian.

Quebec MP Steve Guibord (Patrick Huard) is a small-time MP for a rural Quebec district whose sleepy routine is shattered by two arrivals. First, Souverain Pascal (Irdens Exantus), an earnest twentysomething from Haiti with a head full of political theory, arrives at Guibord’s tiny office, suitcase in hand, for an internship. Then, Guibord ends up with the deciding vote in Parliament to determine whether Canada will go to war. Thrust abruptly into the national limelight, Guibord is torn as the vote splits his constituents and his household. Guibord finds himself leaning on Souverain for guidance as these two fish out of water navigate the absurdities of Canadian politics and try to do the right thing.

Falardeau trades in affectionate caricatures rather than two-dimensional stereotypes, presenting sympathetic portrayals of opposing views even though it’s clear how the film wants us to feel. The only sin in this movie is cynicism: contempt is reserved for the strangely familiar Prime Minister (Paul Doucet), who alternates bald political deal-brokering with enforced piano recitals. (This film was made at a time when seemingly the only thing uniting Canadians was disliking Stephen Harper.) Souverain’s optimism is infectious, invigorating both the jaded Guibord and the audience. My Internship in Canada is a frothy, funny, generous delight.

Patricia Rozema’s Mouthpiece (2019) is something rather more intense and more powerful — though at moments, just as funny. Mouthpiece covers three days with twentysomething Torontonian Cassandra, whose life is upended by the sudden death of her mother. As Cassandra bikes around Toronto getting supplies for the funeral (and avoiding writing the eulogy) she slowly realizes how much of her own life has been lived in reaction to her mother — and how much her mother’s choices were constrained by the patriarchy surrounding them.

What catapults Mouthpiece from a mordant, bittersweet comedy to a truly exceptional art house work is its conceit: in this otherwise realist film, Cassandra is played by two actors (Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava), often acting side by side. The actors alternate, parallel each other, and interact, showing us the contours of Cassandra’s internal conflict. Cassandra is a person, and therefore a lot of things at once. But she can only deal with her grief when she comes to ascribe the same internal complexity to her mother.

An extended interview with Rozema, Sadava, and Nostbakken appears in our forthcoming ebook The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook.

Courtney Small (@SmallMind), Film Critic, Cinema Axis

In a decade with so many wonderful Canadian films, it is easy for a film like Firecrackers to slip under the radar. However, Jasmin Mozaffari’s electrifying debut struck a nerve with me that I have yet to shake. Through the eyes of two young women, Mozaffari constructs a blistering examination of toxic masculinity. Painting a portrait of how poverty, gender, and race all factor into the ways privilege is fostered and enabled, Firecrackers is equally captivating and powerful. While the film has drawn comparisons to the works of Andrea Arnold, Mozaffari proves to be a distinct and unique voice in cinema who is set to shine for decades to come.

An interview with director Mozaffari and her leading actress appears in our forthcoming ebook, The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook.

Justine Smith (@RedRoomRantings), Film Critic

Genèse is a dreamy and transgressive coming of age film looking to redefine conventional narrative cinema.

- Genèse (Philippe Lesage, 2018)

- Tu Dors Nicole (Stéphane Lafleur, 2014)

- Nuit #1 (Anne Émond, 2010)

- A Dangerous Method (David Cronenberg, 2011)

- La part du diable (Luc Bourdon, 2017)

In our forthcoming ebook, The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook, Justine interviews Lesage, profiles the film’s star, Théodore Pellerin, and interviews the editor (the first time an interview with him has appeared in English). Pre-order your copy here.

Orla Smith (@OrlaMango), Executive Editor, Seventh Row

(Honorary Canadian, by virtue of working at Seventh Row)

I’m picking a pair of films, Patricia Rozema’s Mouthpiece (2018) and Sarah Polley’s Take This Waltz (2011), both too exquisite to pick between.

Mouthpiece is the best film I’ve seen this year. Made by an almost all female team, both behind and in front of the camera, it manages to be bold and innovative within the confines of an intimate character study. The main character, Cassandra, is played simultaneously by two different actresses (Amy Nostbakken and Norah Sadava, who both co-wrote the screenplay). The film is a moving exploration of Cassandra’s external and internal journey as she prepares for her mother’s funeral.

While Sarah Polley’s Stories We Tell is her more lauded feature this decade (and for good reason, it’s brilliant), my favourite of hers has to be Take This Waltz. The film looks gorgeous, with blindingly bright, sunkissed cinematography. It’s often quite a warm and funny film, but it’s also pretty devastating. Michelle Williams’ Margot is a woman stuck between two men: one an exciting and mysterious potential lover, the other her husband of several years. Rather than following the rom-com cliche of having the husband be callous and the lover an idyllic alternative, the film treads much murkier moral water. Margot’s husband is absolutely lovely, and they’re very happy together. The uncomfortable truth is that whichever man she chooses, she will be haunted by the path not taken. It’s a film that, in other hands, could have been boring and saccharine, but Polley takes the premise to places that are psychologically fascinating and uncompromising.

An extended interview with Rozema, Sadava, and Nostbakken appears in our forthcoming ebook The 2019 Canadian Cinema Yearbook.

Alexandra West (@ScareAlex), Film Journalist

Canada has long been known for its uncanny ability to excel in the horror genre. From Black Christmas (Bob Clark, 1974) to Prom Night (Paul Lynch, 1980), from The Fly (David Cronenberg, 1986) to Cube (Vincenzo Natali, 1997) to Pontypool (Bruce McDonald, 2008), we Canadians are great at playing with audiences’ deep-seated fears and delivering atmospheric chills.

Following his excellent debut Backcountry (2014), Adam MacDonald’s second film, Pyewacket, expertly combines the eerie paranoia of a young Cronenberg and the sinister energy of Sam Raimi to create a uniquely dark coming-of-age story. As Leah (Nicole Muñoz) grows increasingly at odds with her mother (Laurie Holden), as most teens do, she summons the demon Pyewacket to deal with her monstrous mom. It soon starts to go very wrong very quickly.

MacDonald fills his screen with an eerie woodsy emptiness while driving a simple yet intricate narrative, daring the audience to maintain eye contact with the screen as the peril grows closer. MacDonald and crew’s masterful control of the mise en scène allows Pyewacket to function as a character-driven piece that feels vital, familiar, and exciting while examining our fear of what goes bump in the night and the ties that bind us. Pyewacket will make you care about its characters, then give you nightmares you won’t soon forget.

Addison Wylie (@AddisonWylie), Film Critic, Wylie Writes

Filmmaker Jay Cheel tells a story of synchronicity in How to Build a Time Machine. The documentary’s two subjects (animator Rob Niosi and theoretical physicist Ron Mallett) are two very different people, yet they share a connection through their obsession with H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine — tying directly to each of their primary goals in life. How to Build a Time Machine is about the power of imaginative concepts and how they can shape us into who we are today. This perfect film expands, and even changes, our ideas of passion and madness.