Our annual feature on the best must-see shorts at TIFF 2022 highlights films from around the world and across forms, including Bigger on the Inside and The Flying Sailor.

Read all of our TIFF 2022 coverage here.

Discover one film you didn’t know you needed:

Not in the zeitgeist. Not pushed by streamers.

But still easy to find — and worth sitting with.

And a guide to help you do just that.

Don’t miss out on the best films on the fall film festival circuit

Join our FREE newsletter today to become a Seventh Row inside. You’ll get updates on how to see the best under-the-radar films, up-to-the-minute updates from our festival coverage, and tips on where to catch these near you.

Almost every year since 2015, Seventh Row has published an annual feature (2015, 2016, 2017, 2019, 2020, 2021) on the best short films at the Toronto International Film Festival. Although short films are their own art form, which even seasoned feature filmmakers like Philippe Falardeau and Mina Shum agree are harder to make than features, they are also a great preview of rising talent. Most filmmakers need to prove themselves with a short before they get a budget for a feature.

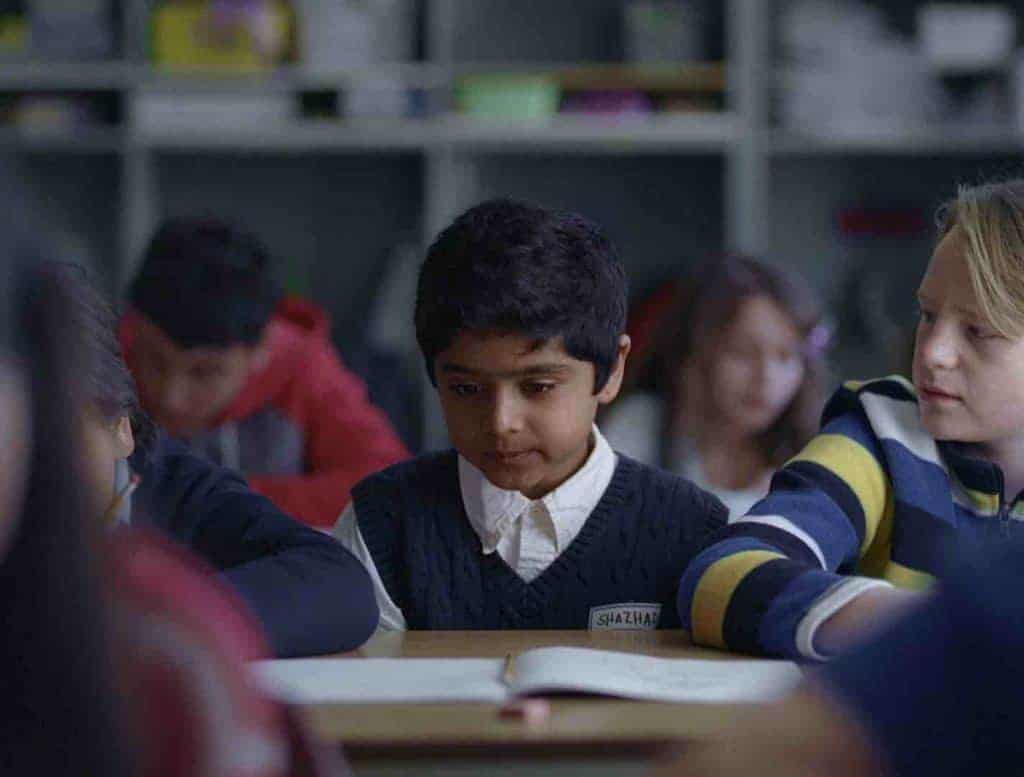

We tend to focus on Canadian shorts, and have discovered some major talent this way. Rebecca Addelman’s The Smoke made our 2016 list of the best shorts at TIFF. She went on to direct the feature Paper Year, a Seventh Row favourite that we loved so much we both interviewed Addelman about it and discussed it on the podcast alongside Sarah Polley’s Take This Waltz. Haya Waseem’s Shahzad was my #1 short of 2016; she screened her feature debut, Quickening, at TIFF last year.

Canadian shorts discoveries at TIFF

Our biggest Canadian short film discoveries to date, though, have been nonfiction films. In 2017, I discovered Caroline Monnet’s work with Tshiuetin, one of the only Indigenous filmmakers out of Canada to be regularly programmed by the festival. Last year, Monnet’s feature debut, Bootlegger was one of our picks for the best films of 2021 (stay tuned for a career profile of Monnet coming this fall!).

In 2019, we discovered the great nonfiction filmmaker Carol Nguyen with her incredible documentary short No Crying at the Dinner Table. I not only interviewed Nguyen about the film, but we ran a masterclass with her and Penny Lane on creative nonfiction filmmaking, which helped inspire our ebook Subjective realities: The art of creative nonfiction. A transcription of the masterclass appears in the book. (This year, Nguyen’s fiction short Nanitic screens at the festival.) In 2020, we were bowled over by both Sophy Romvari’s Still Processing and Sofia Bohdanowicz’s Point and Line in Plane. Justine Smith conducted career interviews with both filmmakers, both of which also appear in the ebook Subjective realities.

International shorts discoveries at TIFF

That said, we do often cover international shorts, especially if they really wow us. Perhaps our biggest discovery to date was Niki Lindroth von Bahr’s stop-motion animated musical The Burden (2017), in which animal puppets sing about existential crises. It was so far and above the other shorts that year that it was the only short we focused on, and we went deep. I interviewed her about this amazing short, which made our list of the top 50 films of the 2010s. She recently directed a segment of the Netflix anthology film The House, which was one of the best films of 2022 so far.

The best shorts at TIFF 2022

This year, the most audacious films are works of creative nonfiction, from American filmmaker Angelo Madsen Minax’s Bigger on the Inside to Sophy Romvari’s It’s What Each Person Needs. But the range of films varies widely, from the animated historical short The Flying Sailor to the abortion story Pleasure Garden to the Joanna Hogg-inspired Honor Swinton Byrne starrer She Always Wins. Make time to see these. They’re excellent works on their own, and they herald a new generation of great filmmakers. Below you’ll find our ten favourite short films screening at TIFF, in alphabetical order by title.

backflip (Nikita Diakur, Germany) is one of the very best must-see shorts at TIFF 2022

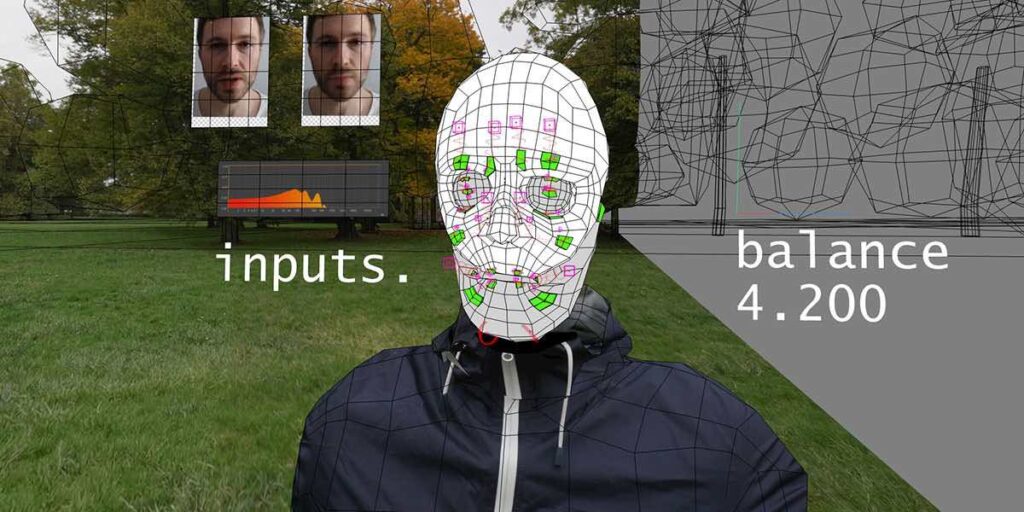

In backflip, director Nikita Diakur speeds us through thousands of hours of computer simulations using machine learning to teach his avatar how to do a backflip. Along the way, he has to learn to walk, stand, turn, get up, and eventually do a backflip. “Attempting a backflip is not exactly safe,” Nikita tells us in a voice created through voice-mimicking software. “You can break your neck, or land on your head, or land badly on your wrists. None of that is nice. But it is nice to have an avatar for that. He can do a backflip for you, just like that, at any time, everywhere. How cool is that?” As it turns out, it’s very cool.

Part animated feature, part computer simulation, part screen life film, and part documentary, backflip defies expectations — including in the ways the body can contort, when it’s computer simulated. Rather than simply running us through the simulations, Diakur places his avatar in specific settings and through sound and light, shows us the passage of time. His avatar begins with trying to walk and do cartwheels in the park in the morning. As the repetitions wear on, it gets darker, and the city sounds change. He decides it’s too dangerous to try to do a backflip outside, so he moves his avatar to his apartment where he can land on a mattress. That helps, but there’s a lot of humour in how the avatar keeps bumping into the desk, computer, lamp — pretty much everything hard, sharp, or fragile.

By this point, you become convinced that Nikita’s avatar is a version of him and not just a computer-generated man with Nikita’s face pasted on. He plays the avatar music to encourage him, and we find ourselves rooting for this non-existent person, too. Pratfalls are inherently funny, but the film finds a particularly weird humour in the fact that we know nobody is actually getting hurt, and Nikita’s avatar can contort in ways actual humans can’t. The animation of the backgrounds is also so vivid that you end up feeling like Nikita really did spend hours jumping in his apartment. Although I laughed a lot, the experience is disorienting, too: can we really get the same pleasure from doing something virtually through our avatars as through an actual in-person experience? As technology advances, and the pandemics make going out and about even scarier, it’s a particularly timely subject to contemplate.

Download a FREE excerpt from the ebook Subjective realities: The art of creative nonfiction film

Explore the spectrum between fiction and nonfiction in documentary filmmaking through films and filmmakers pushing the boundaries of nonfiction film.

There is also a full case study on animated documentaries, much like backflip, and the unique challenges and opportunities of the form.

Bigger on the Inside (Angelo Madsen Minax, US) is one of the best must-see shorts at TIFF 2022

North by Current director Angelo Madsen Minax’s Bigger on the Inside is exactly the kind of film for which we need the term ‘creative nonfiction’. It joyfully plays with the form of documentary, and challenges you to question the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction — both in this film and more generally. It’s a travelogue into the psyche of Minax — or perhaps the character of Minax, as the film is fully scripted — as well as a direct dialogue with the audience. The film is part photographic montage, youtube video montage, text message exchanges, animation, text typed to the audience, and flights of fancy.

It’s a film about loneliness, searching for identity, discomfort in identity, spending time in nature, going down rabbit holes on the internet, looking to connect with others but being afraid or unsure to do so. You might call it an essay film, but you feel like you’ve jumped into his head, John Malkovich style. Bigger on the Inside is densely packed with ideas, has some of the greatest laugh-out-loud moments — both of ‘dialogue’ (in text form) and images. It’s also, at turns, sad, contemplative, and searching. And you’ll want to watch it back immediately.

Bigger on the Inside makes its world premiere in Wavelengths 2: Crisis of Contact.

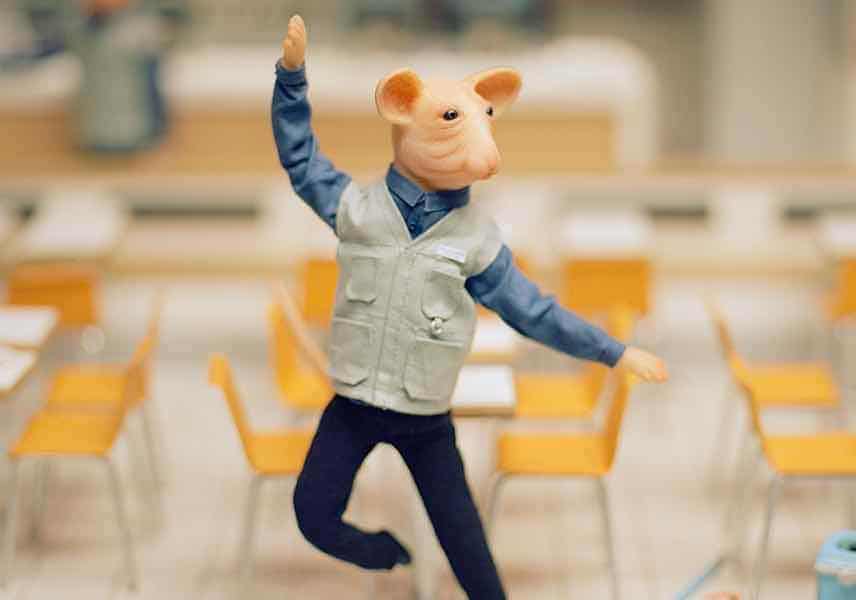

The Flying Sailor (Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby, Canada)

In 1917, two ships collided in the harbour of Halifax, Nova Scotia, one containing TNT, and a major explosion happened. Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby’s vibrant, whimsical, and moving animated short, The Flying Sailor, follows a bystander sailor on a dock who gets shot into the sky when the collision happened. Based on a true story, the film certainly commemorates an important moment of Canadian history, but this is not your typical Canadian Heritage Moment.

The soon-to-be flying sailor quickly loses his clothes, and finds himself floating above the city, recalling moments from his life: scrubbing the shipdeck, running through a field as a child, looking out the window at the sea from his room on a ship. The film feels partly inspired by the Eames’s powers of ten, where a sailor starting on a dock (instead of a man at a picnic), goes up and up and up until he’s entered into outer space, maybe even another galaxy. It’s a journey both internal and external before he comes tumbling back down to earth, changed, but unharmed.

The National Film Board always delivers at festivals, and I’m always glad my tax dollars go to support it. This particular short was produced by David Christensen, who runs the North West Studio and is behind many NFB doc favourites at Seventh Row, including Kímmapiiyipitssini: The Meaning of Empathy and Angry Inuk. I interviewed him in our ebook Subjective realities about how films get funded and supported by the NFB. He offers a lot of great insight into how this national institution is working hard (and well) to tell stories about and for Canadians.

The Flying Sailor makes its world premiere in Short Cuts Programme 1.

It’s What Each Person Needs (Sophy Romvari, Canada)

Having previously floored us with her short Still Processing, one of the very best films of TIFF 2020, Toronto filmmaker Sophy Romvari returns with the assured, thoughtful It’s What Each Person Needs. Moving away from the personal, autobiographical cinema that defined some of her earlier work, It’s What Each Person Needs is the story of a lonely young Jewish woman looking for connection in the online world — through her work as a companion and her relationships with family and friends.

Once again, Romvari plays with the line between fiction and nonfiction: we’re never quite sure if the film is scripted or documentary, especially because the filmmaking is so assured and precise. That is partly because her subject’s story is about the blurred lines between performance and authenticity. Interacting with male clients requires a certain level of performative compassion. But at what point does her need to please as a professional seep into her personal life in helpful or harmful ways? Partway through the film, we hear a phone conversation between Romvari and her subject in which Romvari asks her subject what the film is about — but is this staged, or a sign that the film is indeed nonfiction?

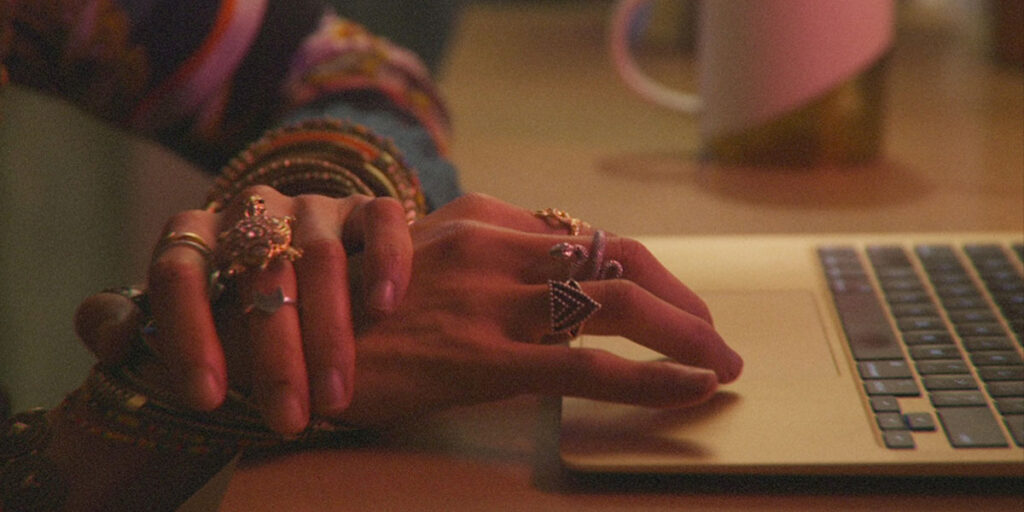

It’s What Each Person Needs is one of the best films I’ve seen to navigate how dominant screens have become in our lives — generally, but also especially since the pandemic. It’s minutes before we even see her protagonist’s face, shot instead in a wide from behind, seated at her computer. Romvari often focuses on details of her subject’s hands, covered in jewelry, or how she holds her phone or sits in relation to her computer screen, rather than on her face. Because she never leaves her apartment, the details of the furniture and the art on the wall often tell us more than seeing the subject’s face. It’s also a thoughtful comment on how even when we see people’s faces on screens, on video chat, we’re not really looking at them — perhaps, especially if they are a hired fantasy.

That’s not to say Romvari never shows us her subject’s expressive face, when she’s excited to make a connection or singing Sondheim’s “Being Alive” over the phone. But it’s the other details that stick and help us feel the same disconnect from the world, herself, and others as Romvari’s subject does.

It’s What Each Person Needs makes its world premiere at TIFF in Short Cuts Programme 6.

An in-depth career profile of Sophy Romvari appears in our ebook on nonfiction filmmaking, Subjective realities: The art of creative nonfiction. Find out more about the book here.

Download a FREE excerpt from the ebook Subjective realities: The art of creative nonfiction film

Explore the spectrum between fiction and nonfiction in documentary filmmaking through films and filmmakers pushing the boundaries of nonfiction film.

The book also contains an in-depth career interview with Sophy Romvari about all of her short films.

Municipal Relaxation Module (Matthew Rankin, Canada) is one of the best must-see shorts at TIFF 2022

Matthew Rankin’s short synopsis for his hilarious tongue-in-cheek short Municipal Relaxation reads, “Ken has an idea for a bench.” The long synopsis reads, “Ken has a great idea for a bench.” A longer synopsis would be that Ken has not only a great idea for a bench, but a lot of very strong feelings about the benches all over Winnipeg, and he will not stop calling the city until he has aired them.

The film plays out largely on a series of 16 mm images of Winnipeg city benches, as we hear Ken narrate his feelings about them into a voicemail box of a city official who never returns his calls. The benches don’t face the right way; they’re in the wrong places; the bench he suggested has now been erected, and he would like some credit. Essentially, we listen to Ken spin out, until, as the film’s title suggests, the ability to vent his frustrations with the world through opining about city benches, seems to have achieved the desired relaxation result.

Municipal Relaxation Module makes its world premiere at TIFF in Short Cuts Programme 2.

No Ghost in the Morgue (Marilyn Cooke, Canada)

Marilyn Cooke’s beautifully photographed and slyly funny No Ghost in the Morgue follows a medical student, Keity (Schelby Jean-Baptiste), in search of an internship — any internship. As the third generation in a family of legendary doctors on the distaff side, there are huge expectations for her. Having failed to get into surgery, she interviews for the last slot available: the pathology internship.

The interview repeatedly plays with our expectations: the interviewer is a white boomer who makes dad jokes. When he asks her, a young Black woman, if she knows about Fiji, we (and she) feel terrified that it’s going to go somewhere bad. But it’s just part of a harmless anecdote about how people change their minds. Nobody wants this internship, but she needs an internship, and he needs an intern, so she gets it. Throughout, there’s a sort of off-kilter humour and danger to the fact that her boss is a quirky white man, who was himself mentored by her recently deceased grandmother.

The film flirts with genre, mostly for humour, though there is, in fact, no ghost in the morgue. On her way to the first day of the job, she watches everyone else get off the elevator until it’s just her, heading to the basement, her very own personal trip to hell. The bodies smell, but the relaxed, laid back humour of the consultant and resident make it a warm, if eerie working environment. The way they treat even dead bodies as people rather than pieces of meat, offers Keity a window into a different way of doing things. And perhaps, a different path forward. Using rich colours — except in the morgue where everything is greys and blues aside from Keity in living colour (bright blues, skin glowing) — Cooke’s film is a warm look at professional disappointment and opportunity, and the business of studying dead bodies.

No Ghost in the Morgue screens in Short Cuts Programme 3.

n’x̌ax̌aitkʷ: Sacred Spirit of the Lake (Asia Youngman, Canada)

There’s so much talent on display in n’x̌ax̌aitkʷ: Sacred Spirit of the Lake that the occasionally jarring special effects don’t detract much from the film’s artistic vision. Written and directed by Indigenous filmmaker Asia Youngman, whose short This Ink Runs Deep was a TIFF 2019, favourite, the film’s premise is akin to a teen scream film, but with a twist. An Indigenous teenage girl new to the suburbs (Kiawentiio of Beans) befriends her white neighbour (Emilie Bierre) who persuades her to come for a nighttime boat ride to look for the legendary sea monster. Youngman sets up all the YA tropes you’d expect from this genre, including the changeup in who the real monster is, but does so as a way of telling a story about the unseen horrors of colonialism.

It’s a film about Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Children (MMIWC) wrapped into an accessible genre film, in line with similar genre approaches to exploring Indigenous trauma like Monkey Beach, Night Raiders, and Blood Quantum. I love the fact that the film never underlines the issues it’s discussing, but I do worry it’s going to be too subtle for a settler audience, especially if TIFF programs it out of context. (It’s the only Indigenous short at the festival this year.) Shooting in rural BC, the film is absolutely gorgeous, making us fall in love with the land even before the film tells us explicitly that it’s not the place of monsters and mystery that settlers might believe. Youngman also gets wonderful performances out of her young cast, especially Kiawentiio and Bierre, both major rising talents in Canadian cinema.

n’x̌ax̌aitkʷ: Sacred Spirit of the Lake makes its world premiere at TIFF in Short Cuts Programme 5.

Same Old (Lloyd Lee Choi, Canada)

Shot in the streets of New York City’s Chinatown, and set during one of the pandemic lockdowns, Canadian filmmaker Lloyd Lee Choi’s Same Old is a little slice of a social realism that proves putting characters in masks won’t destroy your film. In fact, the heightened stress of the pandemic only adds to the film’s righteous indignation that for essential workers, not much changed; it just got worse. The film follows a food delivery worker as he deals with the aftermath of getting his electric bike stolen. The bike is his livelihood, but he’s working paycheck to paycheck to the point that he can’t cover the costs of the stolen bike to continue working. Meanwhile, there are other things to worry about: his fish has died, his elderly parents need to be fed, and there are people around him in even worse situations. Shot by Norm Li (The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open), Choi captures a grainy Chinatown as the sun is setting and into the night, streets ridden with trash — and focuses on the lives of people who run the city but rarely get to drive a film’s plot.

Same Old already screened in the Official Selection (Cinéfondation) at the Cannes Film Festival. Same Old screens in Short Cuts Programme 2.

She Always Wins (Hazel McKibbin, United Kingdom) is one of the best shorts at TIFF 2022

A game of backgammon becomes a passive aggressive site of class warfare in Hazel McKibbin’s She Always Wins. Honor Swinton Byrne — who previously impressed in Joanna Hogg’s duology about a privileged young artist, The Souvenir and The Souvenir Part II — stars as another privileged young woman vacationing with her middle class boyfriend at her family’s estate. He’s older than her, maybe by a decade, and insecure about his lack of wealth when confronted with the lavish lifestyle she leads — complete with silver grapefruit spoons.

When she suggests a game of backgammon, itself a big production because the board is a hand-carved family heirloom, it further sparks his insecurities. As Swinton Byrne’s character does backflips to minimise her privilege, her sister watches this all with disdain, seeing that the man is clearly not worthy. “She always wins,” except she doesn’t this time. She lets him. It’s a small concession, but it’s one of many. McKibbin succeeds at making this board game as stressful and perceptive about class dynamics as a dinner scene in a Joanna Hogg film.

She Always Wins screens in the Short Cuts Programme 2.

Download a FREE excerpt from the ebook on Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir >>

Get the book about The Souvenir

Snag a copy of the first ever book to be written about British filmmaker Joanna Hogg and her process.

As a chronicle of the making of Hogg’s first Souvenir film, Tour of memories is a perfect companion to The Souvenir Part II, a film about the making of The Souvenir.

Pleasure Garden (Rita Ferrando, Canada)

How do you talk about abortion? The couple in Pleasure Garden don’t know, though writer-director Rita Ferrando keeps it ambiguous about whether or not this is problematic. Instead, Ferrando brilliantly uses sound design to get us into her protagonist’s (Daiva Foy) conflicted or perhaps ambivalent mind. When the film opens, she calmly and quietly eats a peach, gets barraged by the loud sounds of the city streets outside her window, cries softly on the couch. Then, she hops on the screeching loud subway to meet her boyfriend (Ishan Mehta, who has previously been credited as Ishan Davé for his great work in Mouthpiece and Sugar Daddy). On the ride, she remembers an encounter with a pharmacist who explained how the abortion pills work. Ferrando shoots only the pharmacist’s hands and the glass window that separates her protagonist from the pharmacist. It’s alienating.

There’s a lot to decipher in the body language between the couple, which itself seems ambivalent. They meet at the tight subway station with a clutching hug. They return to his apartment, on his bed, where he asks if she wants to talk, and she says no. They awkwardly lie there, not touching, as the high-pitched sounds of the fridge and electronics infuse the soundscape. Yet there is tenderness, especially seen post-abortion on a small vacation they take to a lake. We hear the sounds of fabric on skin, see light caresses in the water. Do they not speak because they know each other so well? Or is there a rift related or unrelated to the abortion? The final image of the film is especially evocative and puzzling: is this what love looks like, or is it the beginning of the end?

Given the current political situation, any film about abortion is welcome, especially one that deals with the practicalities — going to the pharmacist, taking the pill. The boyfriend is supportive, but ultimately, she takes the pills by herself; it’s a bodily experience for her alone. In a strange coincidence, it’s one of two films at TIFF this year (the other being the feature Until Branches Bend) to prominently feature both peaches and abortion (not at the same time). The often harsh sound design recalls Gillian Armstrong’s 1973 short, One Hundred a Day (now on Criterion Channel), in which the very, very loud sounds of the factory where the protagonist works seem to mirror her fear of getting a backstreet abortion. Fortunately, the abortion in Pleasure Garden is much safer and calmer, but the disorientation remains.

Pleasure Garden makes its world premiere in TIFF Short Cuts Programe 3.

Don’t miss out on the best films on the fall film festival circuit

Join our FREE newsletter today to become a Seventh Row inside. You’ll get updates on how to see the best under-the-radar films, up-to-the-minute updates from our festival coverage, and tips on where to catch these near you.

Discover some of our favourite short films discovered at TIFF

Become a Seventh Row insider

Be the first to know about the most exciting emerging actors and the best new films, well before other outlets dedicate space to them, if they even do.